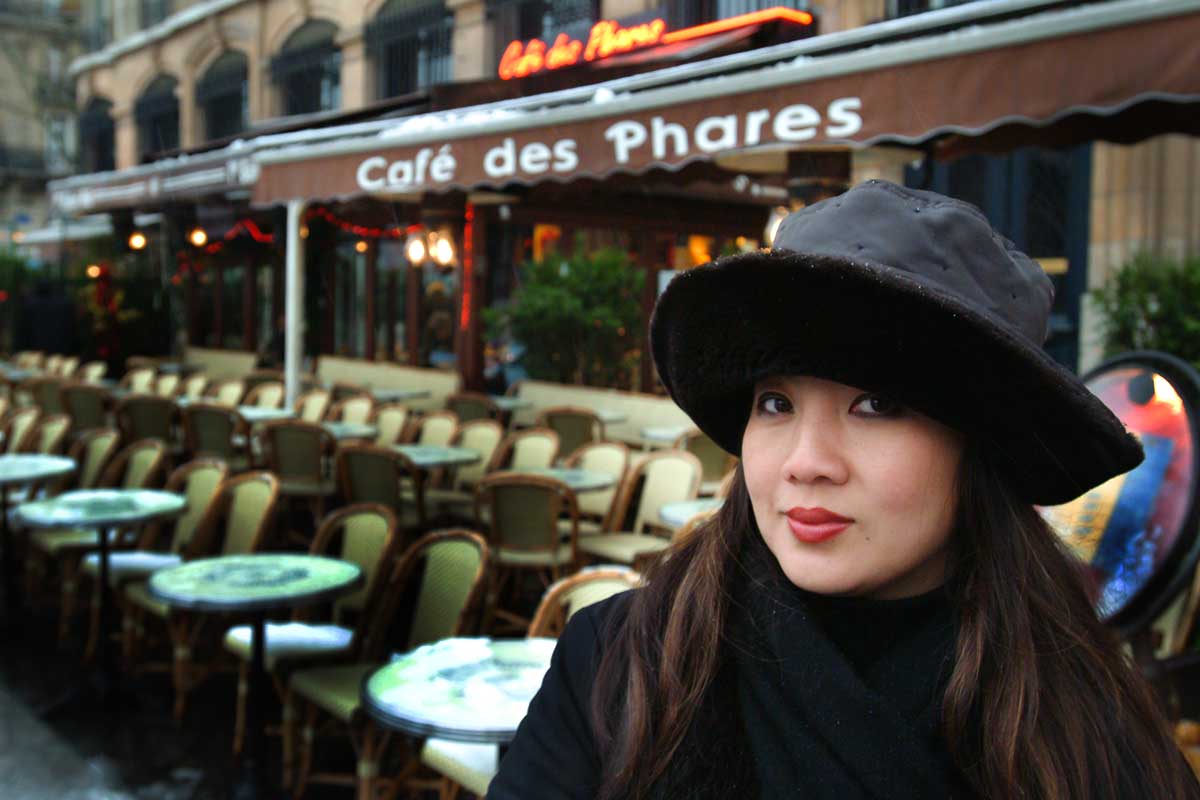

With the recent and appalling increase in violence toward those of Asian backgrounds, we reached out to Kim Sunée, a writer whose words and way of seeing the world we have long appreciated, to inquire if she would share with us her experience of this challenging time. This is what she so beautifully wrote.

Almost daily, it seems I have to recalibrate, like a neglected oven, the temperature of the moment. I barely have time to wash my face in the morning and stretch into the day before my teenage stepson begins to ask questions.

Tall, lean, with big eyes and thick waves of hair, no one would guess that he is one quarter Asian. When he overhears me telling my husband about a writing assignment that touches on traditional cooking in times of turmoil, and more specifically during a time when we’re faced with a rise in Asian-American hate crimes, he looks up from his baseball book and asks, with both concern and surprise, “But that hasn’t affected you, really, has it? No one has hurt you.”

More affirmation than question, his assertion that I haven’t been targeted physically seems enough to reassure him. For now. We sometimes forget how our kids strain to listen to every word, every excruciating detail of our whispered conversations. They are always on the hunt for signs of disruption, clues to any imminent danger that might collapse their world, even if that consists mostly–in my son’s case anyway–of attending virtual school, perfecting his curveball, playing guitar, and eating.

Because we’ve been hunkered down for more than a year and our social interactions have been reduced, he’s heard and experienced enough that I don’t offer up the usual talk about empathy and responsibility toward our neglected communities. Truth be told, I, too, am overwhelmed by everything, specifically the rise in hate crimes. Anything I say these days always seems inadequate at best.

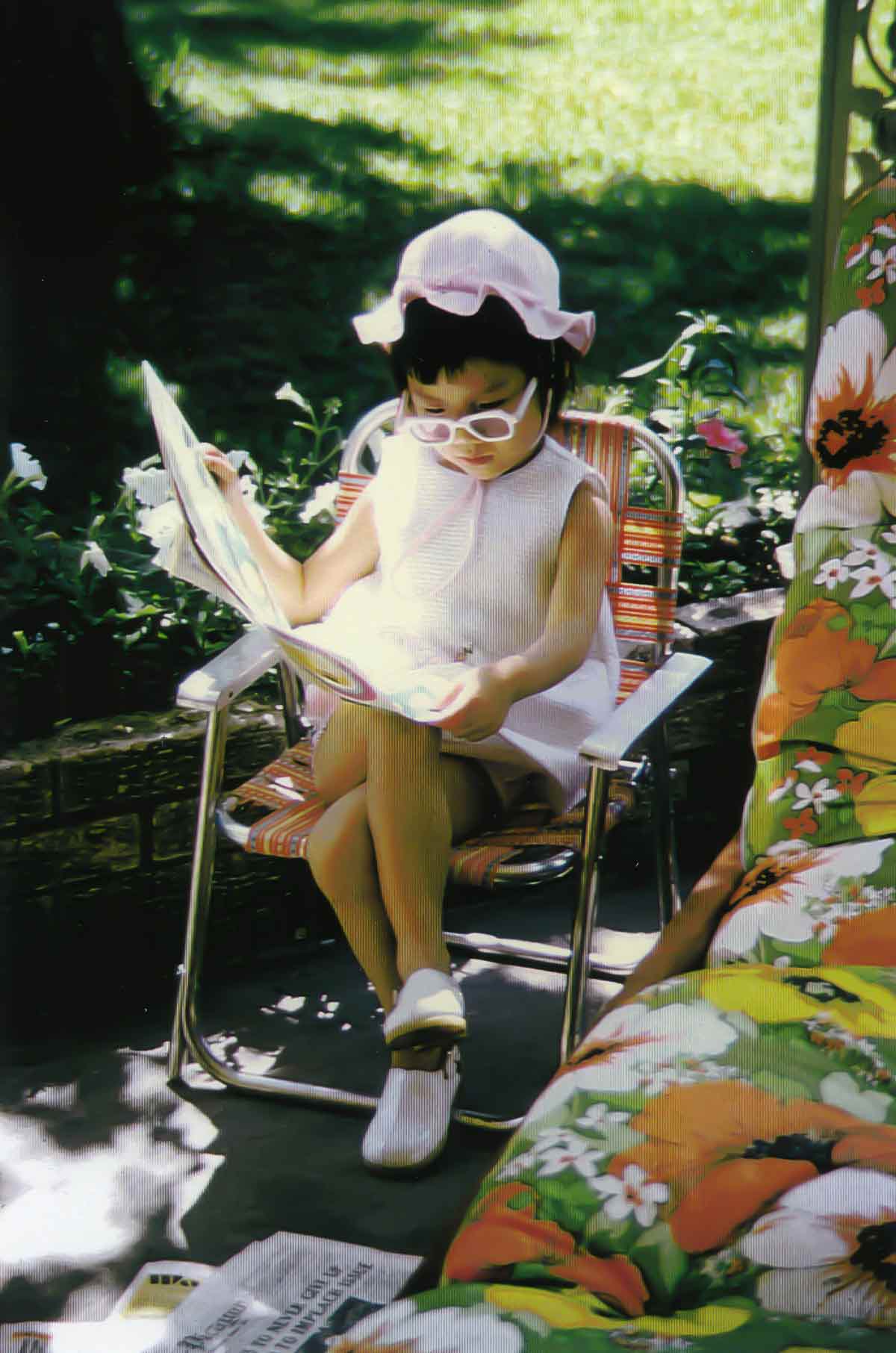

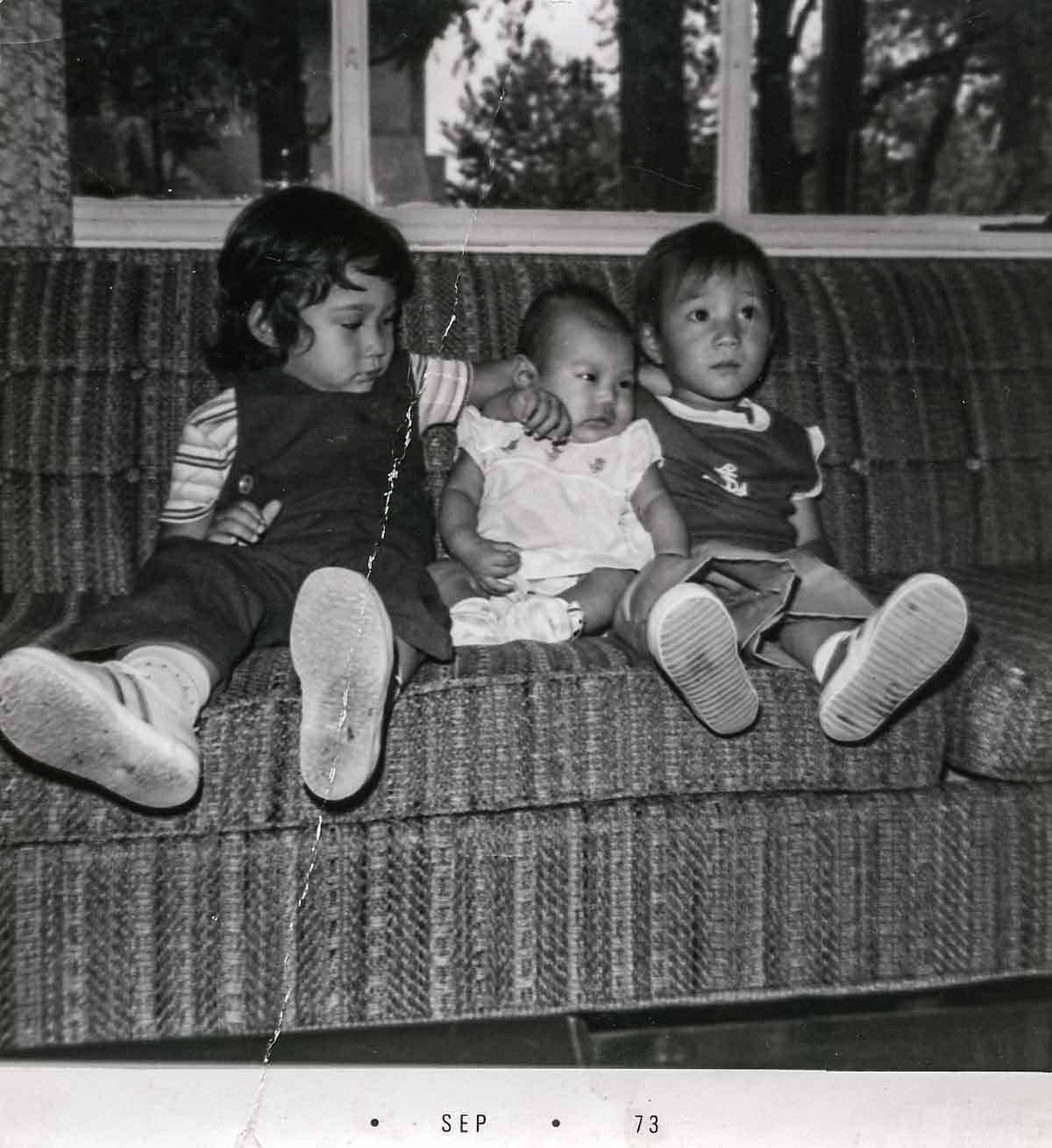

So I don’t mention the boys from my grade school in New Orleans and how they used to call my sister and me chinks and ching-chong and tug their eyes into knife slits. They were ignorant of the fact that we had been adopted from South Korea as toddlers, had became naturalized Americans, and already spoke better English than most students in our class.

Or the time when I was barely twenty, standing on a busy street corner in downtown Stockholm waiting to meet friends at a local café, and a small, determined-looking man pointed at me and asked if I was his new wife. When I told him no, he insisted, following me with his fist clenched in the air and shouting, “I paid for you, all the way from Thailand. Du kommer med mej! You come with me!”

I have often turned the other way, trying to follow my own path, from an orphanage in Seoul to various port cities and on to 10 formative years in Paris and the Alps of Haute Provence. In between, a spinning globe of countries and vocabularies, foods, and kitchens, from Birmingham to Cayenne, in which I learned to hone not just my knives but a razor-sharp survival instinct that protected me along the way.

So in times of distress, I am perhaps most myself in the kitchen and turn to what I do best. An unapologetic feeder and nurturer, I have learned that food is my love language. At first, grateful to be able to be hunkered down with my family in the first months of the pandemic, I experimented with all sorts of sauces and usually ended up with curdled, broken messes. A metaphor, for sure, and I quickly realized that I was simply trying too hard. Trying to make things normal when there was nothing familiar.

With a teenager navigating online classes, a husband running a company from the dining table, and neighbors in need of nourishment, I was determined to make good food each day anew. I made fried chicken dipped in the last of the milk and vinegar to mimic buttermilk. We devoured lamb biryani from our neighbor, who often shares the flavors of her home state of Kerala. Her German husband and native Alaskan kids took turns stopping by to pick up chicken and dumplings, jambalaya, and kimchi fried rice that I made for them in exchange. When we thought it was safe, we ordered takeout to support our local restaurants.

Watching the ever-growing food lines across our country, I felt guilty for having any amount of food stored away in the pantry and freezer. Any ingredients that might soon go to waste found their way into a surprise batch of nachos for second lunch, nourishing our worried Hobbit souls. We ate but were always hungry, for some far-flung adventure, any escape from the daily routine of our new reality.

Everyone cheered when I gave in at around week four of lockdown. I had been trying to make healthful foods until that time and would usually insist on organic and sustainably raised ingredients. There was a momentary silence as I heated up a neglected bag of frozen fried onion rings. We ate every last crumb, piping hot and dipped in homemade mayo spiked with horseradish and chili crunch.

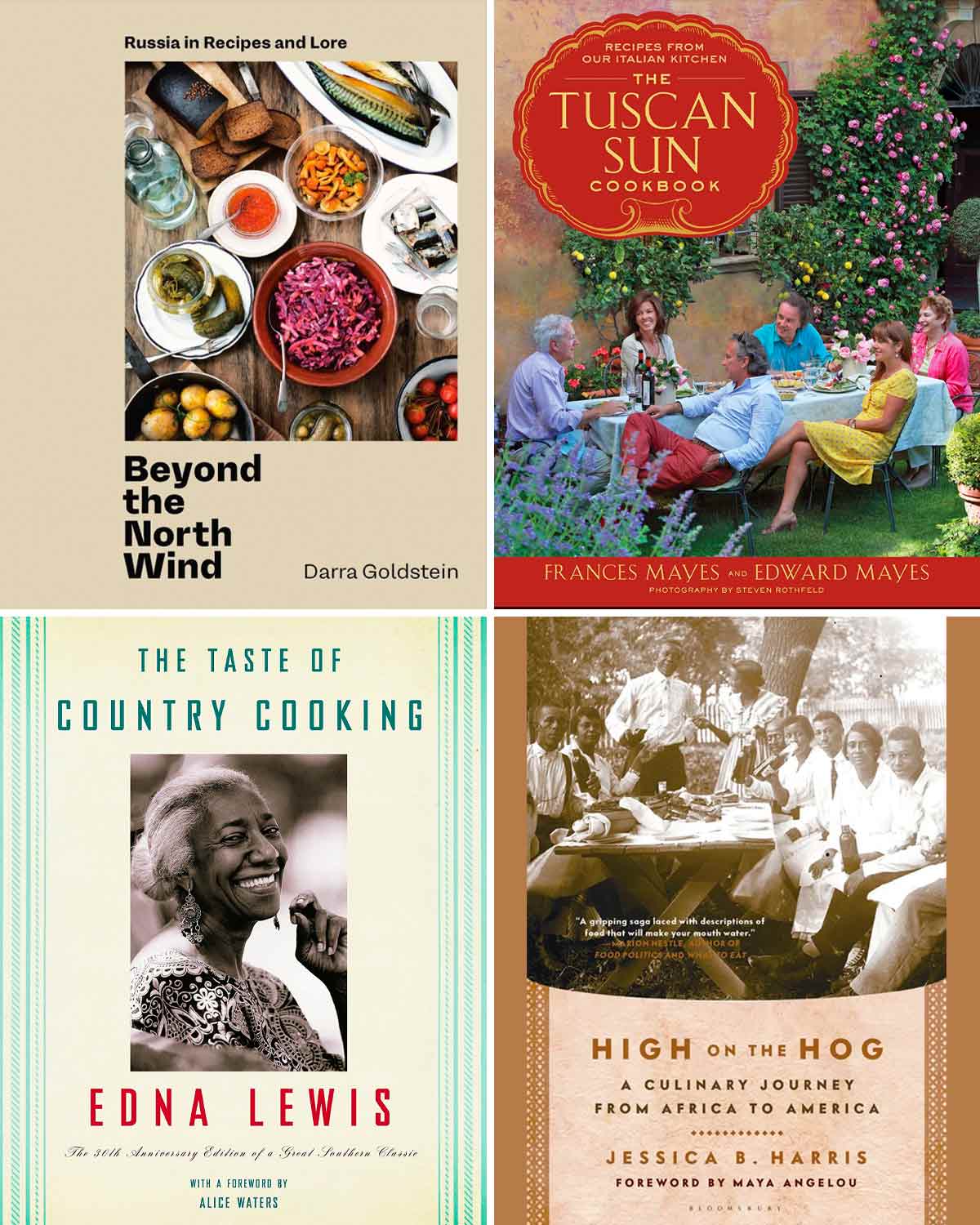

And because we missed friends and traveling, I turned to them and beyond for their comfort foods. From our stash of frozen berries sprung Sara Foster’s strawberry tres leches and with it a familiar return to her North Carolina kitchen. Savory sformati sent me back to a summer in Cortona, as rich and gladdening as the days spent cooking with Frances and Ed for The Tuscan Sun Cookbook. Vowing to have a few no-news hours, I rushed to cook from Darra Goldstein’s Beyond the North Wind, an exquisite love letter to the heart of Russian food, and learned the language of sourdough and sparkling beet kvass. When I dove for seafood in the freezer, we docked in Portland for a cold zakuski spread prepared by Chef Vitaly Paley. (His grandmother’s “fish under a marinade,” pan-fried and piled high with tomato, carrot, and horseradish, has become our go-to favorite preparation for cod.)

When the sun rose at 10 am and set again only four hours later, I’d riff on Andrea Ngyuen’s hot sauce recipes, enlisting the green-speckled papayas and scotch bonnet chiles sent from my friend’s garden in Miami. And to continue southward, I revisited Edna Lewis, Michael Twitty, and the always regal Jessica “Queen B” Harris. I’d call my friend, Adolfo, back in New Orleans, and we’d debate the merits of dirty rice and the history of escabeche. As the winter holidays approached, accepting that we wouldn’t be hosting the traditional dinner for a dozen or so guests, I tucked into Christmas cakes and steamed puddings via Nigel Slater’s kitchen chronicles, small points of light in the long winter months to come.

What I wasn’t telling anyone was that despite the refuge of my kitchen, there were so many moments when I foundered. Crying quietly in the bath over videos of an elderly Asian woman being beaten repeatedly because of the shape of her face and the color of her skin. Knowing that each day, thousands were dying–whether due to illness, violent crime, or the natural course of life itself. And closer to home, experiencing our small bubble losing mentors, colleagues, and parents. But I still believed that food could be a balm. Somewhere I had learned to fold in my deepest fears and anxieties along with butter and egg whites. And I was determined to continue to cook for others in hopes of offering even the smallest bit of solace.

Each day as we depleted our larder and hoped that we were another day closer to an end, we debated whether or not our patience and vigilance would reward us. Early on, though, I somehow felt energized and determined; defying the Arctic cold, I walked solo early in the dark mornings, setting the intention for the day, vowing with each crunch of my boot on ice, not to give up, not to give in.

And then a message pinged in my inbox from an older Korean woman who had been following my trail of crumbs on social media. She was direct in her admonishment. “Sunée, where are all the pictures of Korean food, your food!?” I could hear the chop chop of this ajumma’s voice. Just because I wasn’t posting each and every bite I cooked, she wrongly assumed that there weren’t banchan—the rainbow of pickled and fermented sides that accompany every Korean meal—at the ready along with stashes of dried anchovy and fermented bean pastes next to bags of “00” flour and stacks of exquisitely wrapped tins of tuna from Portugal.

My initial reaction was one of shame. I started to write back a hurried response in my defense, but wondered to myself, “Perhaps thou doth protest too much?” So I acknowledged her note by sending a quick but thoughtful message and called my friend Lee Herrick, a poet who had been adopted at 10 months and raised in California. He and I met in Seoul back in 2008 when he was doing a birth family search. He reminded me that Koreans often feel their food is the only food. “That ajumma didn’t grow up in New Orleans like you did. She didn’t live in France, and eat and cook her way through Europe for ten years,” he said. “Food is national…as much as it brings people together, it can be divisive, a source of cultural and familial pride.”

Lee and I talked about comfort foods and agreed that japchae, the sweet potato noodle dish popular in Korea for celebratory and holiday meals, is worth the time and precision required to make it just right. But we also acknowledged that we’d be hard-pressed to find anyone–adopted or not–raised in Southern California and beyond who didn’t also love tacos. What about the Korean adoptee raised in Minneapolis or Michigan? Can’t she also claim pizza and lasagna as hers?

During this same conversation, I was reminded of a television producer who once told me that I’d be more marketable if I could just “stay in my lane” and focus on Asian food. General Asian. “None of that kimchi voodoo.” The producer also liked that I was a banana, or, as he described, “yellow on the outside but white on the inside.” He had said it all so casually, and with such great conviction, that he was perhaps genuinely shocked when I told him what he could do with his banana.

Who has the authority to tell any of us what is or isn’t our food? And can’t food sometimes just be what it is?

I see cooking competitions in which home cooks are berated for not streamlining a more obvious “culinary point of view.” Cue the host’s exaggerated eye roll to the camera as a brown-colored chef presents a classic French beurre blanc sauce. No one tells the white chef who spent a single year in Tuscany that she can’t cook risotto and osso bucco. But put a dark face or slanted eyes behind that same dish—someone who may have grown up or spent decades living and eating in that country—and they will be discounted, at best. In other words, we are told in no uncertain terms, “Stay in your lane.”

There are endless stories of mistaken identity, deliberate exclusion, and lightly veiled bigotry. In my case, some by women but mostly by men who declare someone who looks like me to be a prize or a delicate chinoiserie, an exotic bird. Over the years, I’ve always thought but never quite had the courage to say out loud, “I am not your exotic…”

If you are Other, whether based on gender or color or size, you are taught to assimilate, to be better, to work harder, to become even more while somehow becoming less. Less visible, less curious, less vocal. Less you.

How many layers are we to shed in order to be considered not too much, not too dangerous? And my sisters, some with even darker skin and eyes than mine, are we relegated to squatting next to open fires, stirring only the curries and long-simmered stews, the fermented foods and charred chiles of our birthright?

I’m probably more “qualified” to share recipes for soupe d’épeautre and bourride de poissons thanks to the decade I spent in France, Provence in particular, embracing with full heart and stomach the flavors and history of the region. So many evenings spent setting outdoor tables with platters of warm summer peaches and tomatoes, shriveled olives, and the first pale green almonds, raw and tender, to be dipped in salt. I learned to time my visits to nearby villages according to the schedule of the roving markets, always making my way back to Daniel, the butcher in our little village, who took great pains and pleasure with each order while I watched the ballet of his hands as he expertly wrapped garlicky pâté-like caillette or a leg of cabrito. My new favorite words were always food-related: pistou, pissaladière…I even mimicked the roosters as they sang out in their own language, “Co-co-ri-co. Co-co-ri-co.” For years, there was not a vat of kimchi in sight.

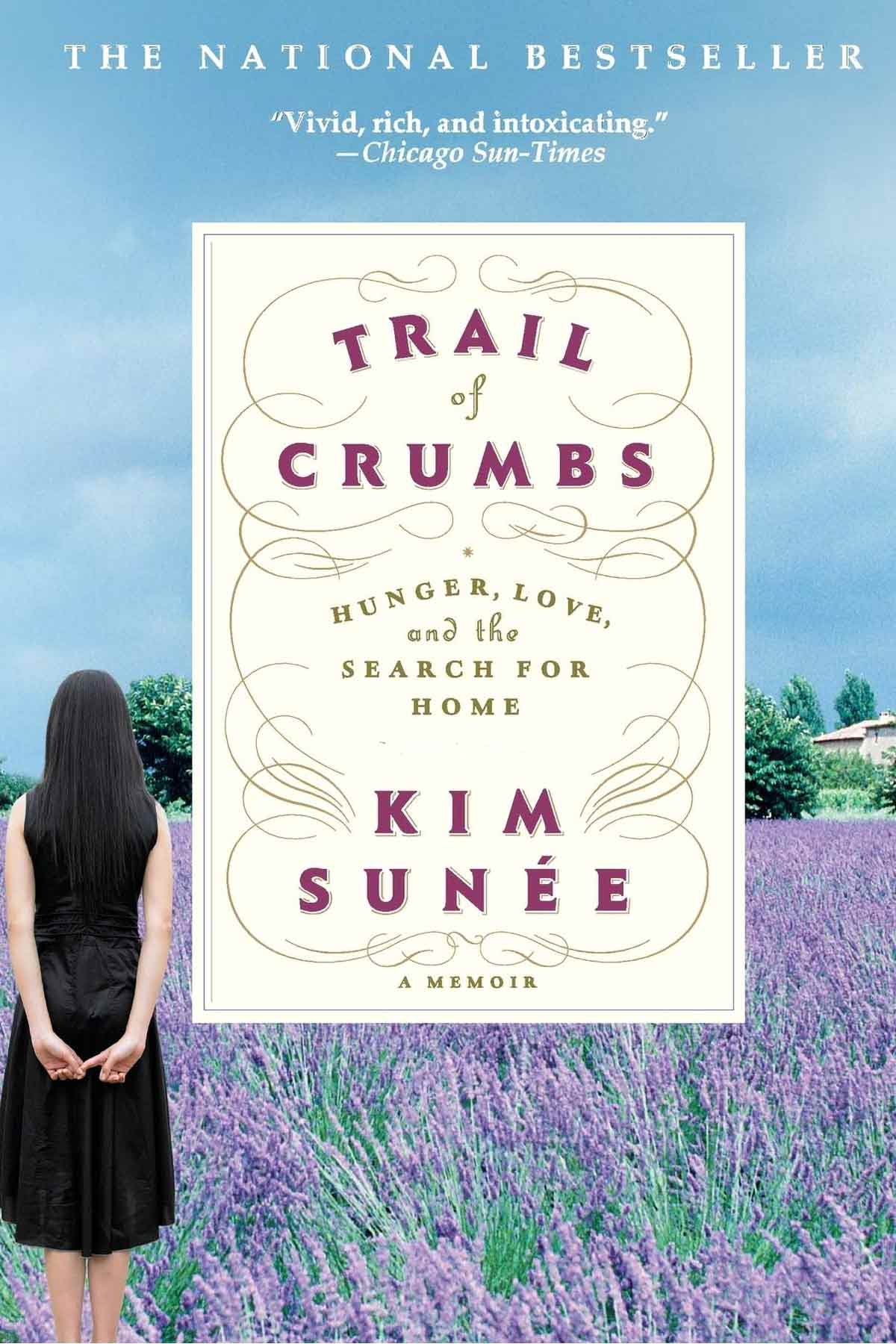

Some of the comfort foods I turn to do indeed include the holy trinity of gochujang, tteok, and cucumber kimchi. With that ajumma’s voice as a reminder, I revisited the recipes from a cookbook, Everyday Korean, I co-wrote with Seung Hee Lee. We first met in 2008, during the book tour for the Korean-language edition of my memoir, Trail of Crumbs. During an emotional journey through Seoul—revisiting orphanages and markets in hopes that I might find some trace of my birth family—we ate and drank with gusto, promising to remain sisters in the kitchen.

During that same journey, we had the great fortune, thanks to Seung, to spend a day at the prestigious Taste of Korea Institute that is dedicated to the preservation of royal court cuisine and the updating of traditional recipes for modern kitchens. At first, I was allowed to observe. Eventually, I was invited to help prep under strict surveillance. Cleaver in hand, I watched as those women deftly fashioned egg yolks and whites, cooked separately, into perfect diamond shapes to garnish short ribs braised in a fragrant sauce of soy, brown sugar, and ginger. Together we steamed large flat rice cakes in nettle-like ramie leaves. I was gently scolded for not slicing the raw chestnuts and fresh jujube into equal-sized julienne pieces.

I was happy in that kitchen, despite my inadequacies and the occasional grunts at my shoddy knife skills, with those women whose faces reflected mine, doing the thoughtful and tedious work of generations of cooks before us. As we tasted along the way, I wondered what my Korean mother might have cooked for me and the brother I still remember. I longed to recognize myself in the shape of her eyes, momentarily lodge myself in the deepest chambers of her culinary heart.

There were no exotic wallflowers in that group. With our thick forearms and solid stance, we were not some fragile china dolls from a mail-order catalogue. We were no one’s platform or cause, no harbinger of foreign viruses.

So, until the TV executive who tells me to stay in my lane moves over, or the woman who yells for me to go back to my country studies her own twisted roots, I will continue to cook and share the foods that make me who I am. Not just at face value, but the whole of me.

Koreans have an elusive word, han, to indicate a collective grief and longing. For some it signifies both despair and hope, for others, a deep regret. It is not unlike the Portuguese saudade, which resonates with me more in that it also embraces a craving for a happiness that once was.

When cooking, I often listen to my spiritual auntie, Cesária Évora, and lean into her mornas, those minor-key ballads of longing, loss, and a desire for that which is past, that which might have been. Orphaned as a child, she started making her way in the world at age 15, barefoot always and grounded.

So as I step into the quiet kitchen of the night, lighting burners and prepping my mise, I wonder if I have talked myself into believing that even in these times, acts of cooking can ease our longings and our greatest fears. Turning up the volume, I listen to Cesária as she teaches me, even in pain and yearning, there is room for joy and celebration. A promise of give and return. My han for her Sodade.

We’ll damn, Kim, so well expressed. Screw those dolts who crossed your paths. You brought so much here to Bham.

— Bill K

Thanks, Bill. I’m so glad to hear from you here.

And grateful always for when the stars align…you and Jeanetta were a big part of my journey in BHAM.

As for Kim’s writing she hit the nail on the head. The idea as food being a love language, I have often thought that, just never found the words to express it as she has. I have often shared food with other cultures and find it amazing we learn about each other across the table.

Joseph, thanks for reading my piece and sharing your thoughts. Food is such a powerful love language and I feel fortunate to be able to learn and share so much from others’ culinary vocabularies.

Is there a particular cuisine you turn to in times of distress or to communicate your love to others?

It would either be Filipino or Indian for me. Indian because I have always had it by my side throughout life and its warmth while cooking. Plus, the range of spices allows for endless combinations. The only problem is once you find the recipe that you love so much, it is hard to move on from there.

As for Filipino, I went from thinking it was awful (based on a limited experience, namely a bad eatery in town) to find it an exciting, unique cuisine. It is probably also tied to my church, where the Filipino folks there (particularly the women) were warm and welcoming upon my baptism.

Not a cuisine, but more so a dish – chilli. Especially on a cold night or a brisk day, having it bubble away on the stove or in the slow cooker. I guess what the right food in your said circumstance would be whatever would feel comforting if you were brought in from the snow in the freezing dark. If this chili is not an example, I have no idea what would be.

Fantastic read, by the by.

I wholly agree about Indian food–so vast and varied and warming. I’m less familiar with Filipino cuisine, which is fascinating in so many ways. I had a neighbor from the Philippines and she used to make and share hot fried lumpia, garlic rice, and adobo.

Thanks for sharing your chili recipe. I have one on kimsunee.com that is sans beans and uses lots of dried chiles.

But I’ll try this one as well. Happy Cooking and Eating!–KS

“Not just at face value, but the whole of me” is exactly how Suneé writes too! It’s always going to be hard to face the unsavory parts of society, but it’s always better to do it together. Thank you for this piece!

Thank YOU for taking the time to read this piece…and while you’re here, Scott, there are tons of recipes you’d love on this site.