David and I agree on very little in life. That’s a topic for another day. But one thing we’re both curious about is the reason for how we feel when we adhere to a relatively low-carb way of eating. While we still take pleasure in eating, we wanted to learn more about the science behind a more modest intake of carbs. So we sought out one of the most knowledgable and controversial authorities on the topic, investigative science journalist Gary Taubes, so he could elucidate us with his understanding of the science of weight loss following years of research. Here’s what he had to say.—Renee Schettler

Chat with us

Have a cooking question, query, or quagmire you’d like Renee and David to answer? Click that big-mouth button to the right to leave us a recorded message. Just enter your name and email address, press record, and talk away. We’ll definitely get back to you. And who knows? Maybe you’ll be featured on the show!

The Case for Keto

David Leite: Hey, Renee, were you a pudgy kid?

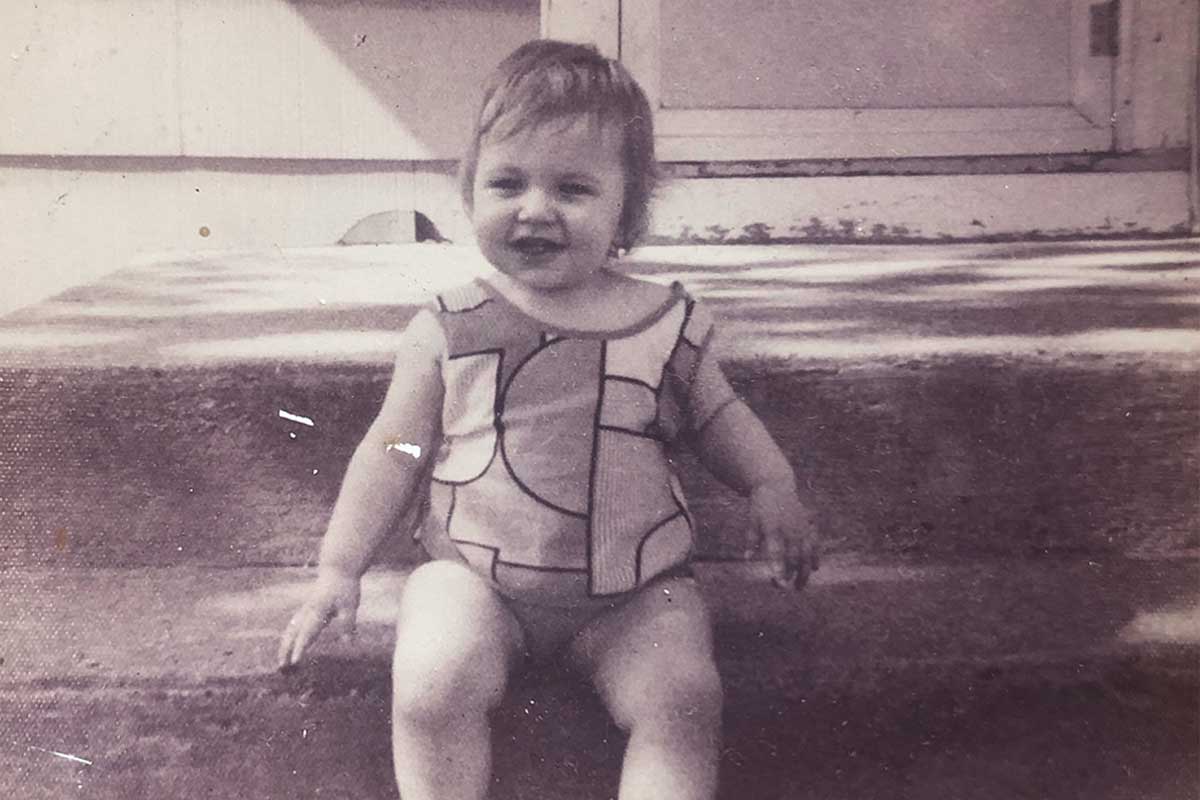

Renee Schettler: [Laughs] I think pudgy is a good word to describe it. I’ve got this great photo of me sitting on the steps of my farmhouse, I must have been maybe two and a half years old, and I’ve got these little rolls of pudge on my arms and my legs, and it’s really sweet. I’m actually, for the record, wearing a very fashionable geometric-design ’70s dress. My mom had a similar photo taken of her on her farmhouse steps as a child and I call them our “generational ghetto photos.” We were both pudgy as can be, as little kids ought to be.

David: Yes.

Renee: So yeah, I was pudgy. It took me a while, until about 13, to lose the pudginess, actually. What about you?

David: I was a pudgy kid and it took me probably until my late teens to lose it, but I always carried around a little extra weight. Always did. Then I gained a real lot in my 20s when I was going through a real bad depression and I was working at Windows on the World, so I just ate and ate and ate and ate and I gained 70-something pounds. Then I lost it and I kept it off. Really, I beat all the odds. I kept it off for about 10 or 12 years, then hello, food writing.

Renee: Ah. Yeah, it’s tricky, food writing.

David: It is. Then I started to gain and gain and gain. I gained a tremendous, tremendous amount of weight. Since then, I’ve battled my weight even more, and so dieting has been a part of my life, I think a part of almost everyone’s life, for most of my life. It’s really been harder as I’ve gotten older. My god. Hit 50, forget it. Hit 60, forget it.

Renee: I hear you. Well, I’m not 50 yet, but I completely get it. I started dieting when I was 12, that’s how I lost the weight. I saw a picture of myself in a bathing suit, and I was like, “Yeah, that’s not going to work.” And then I did really well, I was always very athletic, so while it wasn’t easy to stay thin, it was easier. Then I ended up in a cast, I couldn’t run, and I gained some weight. It gets really tricky, the whole food and emotions thing, as you said. They’re inextricably intertwined.

David: In addition to the emotions that get tied into that and the psychology, there’s also the science of eating and the science of dieting. I think a lot of people put a lot of weight, no pun intended, on the emotional aspect, and the psychological aspect, and that really is very valuable, but there is just some of this that is true hardcore science.

Renee: Sure.

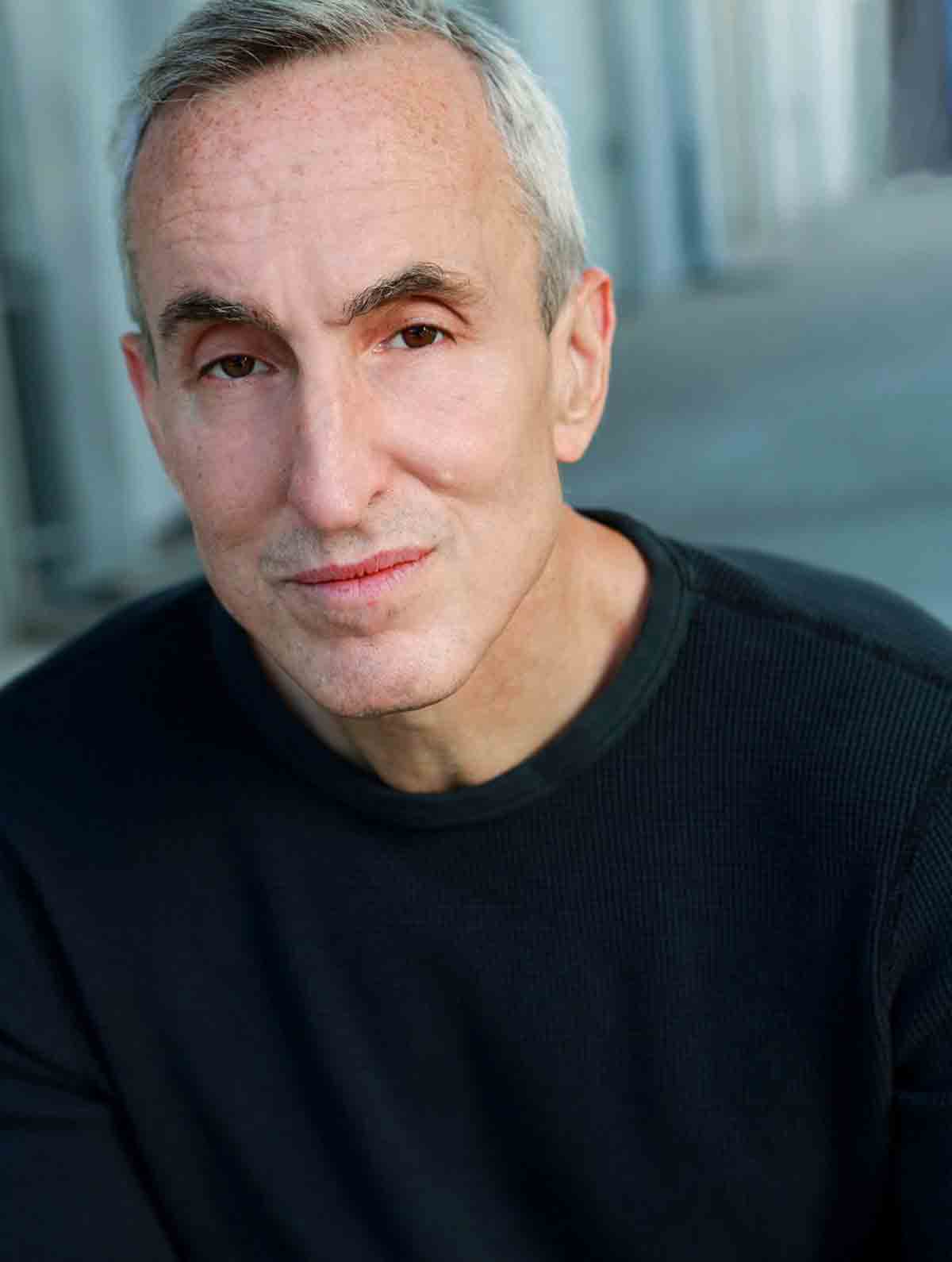

David: Of course, now what’s happening is this real battle in the weight-loss world when it comes to keto. Everybody has opinions on keto: that it’s not good for you, that it’s extremely good for you, that it’s bad for your cholesterol, that it actually lowers your cholesterol, that it lowers your blood pressure. There’s so much infighting. Our guest today knows all about the science of weight loss. For more than 20 years, Gary Taubes has been an investigative science and health journalist. He’s the author of Why We Get Fat, Good Calories, Bad Calories and his newest book is The Case for Keto: Rethinking Weight Control and the Science and Practice of Low Carb/High Fat Eating. I think we can learn a real lot from him and maybe find out why you as that little kid were pudgy on your farmhouse steps.

Renee: And how I can not turn pudgy again even after 50.

David: Exactly.

Renee: I’m Renee Schettler, editor-in-chief of the website Leite’s Culinaria.

David: And I’m David Leite, its founder, and this is Talking With My Mouth Full, a podcast devoted to all things food, the people who make it, and the stories that make the people. Welcome to the show, Gary.

Renee: Thanks for being here, Gary.

Gary Taubes: Thank you for having me.

Why keto?

David: So Gary, explain to our readers, you and I have met, you and I have had breakfast together, although you didn’t eat, I ate, but here you are a journalist writing this book on keto. What’s your reason for doing this and why did you write this book?

Gary: I was an investigative science journalist in my youth, with a hard science background, and in the ’90s, I stumbled into public health research because, quite frankly, the research was so poorly done. The gist of it is, when you’re asking questions about the environment and health, you can’t really test your hypothesis. So science is a process of hypothesis and test, and when you’re looking at these very important questions about, particularly about disease, they’re very, almost perhaps impossible, to test, and so a lot of assumptions are embraced.

By the late ’90s, I did a series of investigative articles for the journal Science on the dietary dogma we had all grown up with, and I believed in this as much as anyone. That salt consumption causes hypertension was the first one. That dietary fat is the cause of heart disease was the second. In both cases, both articles, I won major science journalism awards, and in both cases the evidence supporting our beliefs just wasn’t there. So the nutrition heart disease research communities had, in effect, fallen in love with the hypothesis, they then tested the hypothesis as best they could, and the hypothesis failed the test. So, and this is typical for bad science everywhere, they decided they must have done the tests wrong and they were going to believe the hypothesis anyway and they were going to convince the rest of the country and then the world to do so.

So by early 2000, I was looking into the obesity epidemic and what the possible cause was, and there were a few possibilities. One of them was that Americans just started eating too much, and the other was that the kinds of foods we were eating changed. We embraced this idea that carbohydrate-rich foods were heart-healthy diet foods. Until the 1960s, carbs were considered inherently fattening. One of my favorite articles I quote in virtually every book I’ve written on this, probably every book, was a 1963 article in the British Journal of Nutrition, coauthored by one of the two leading British dieticians, and the first sentence was, “Every woman knows that carbohydrates are fattening.”

Renee: Wow.

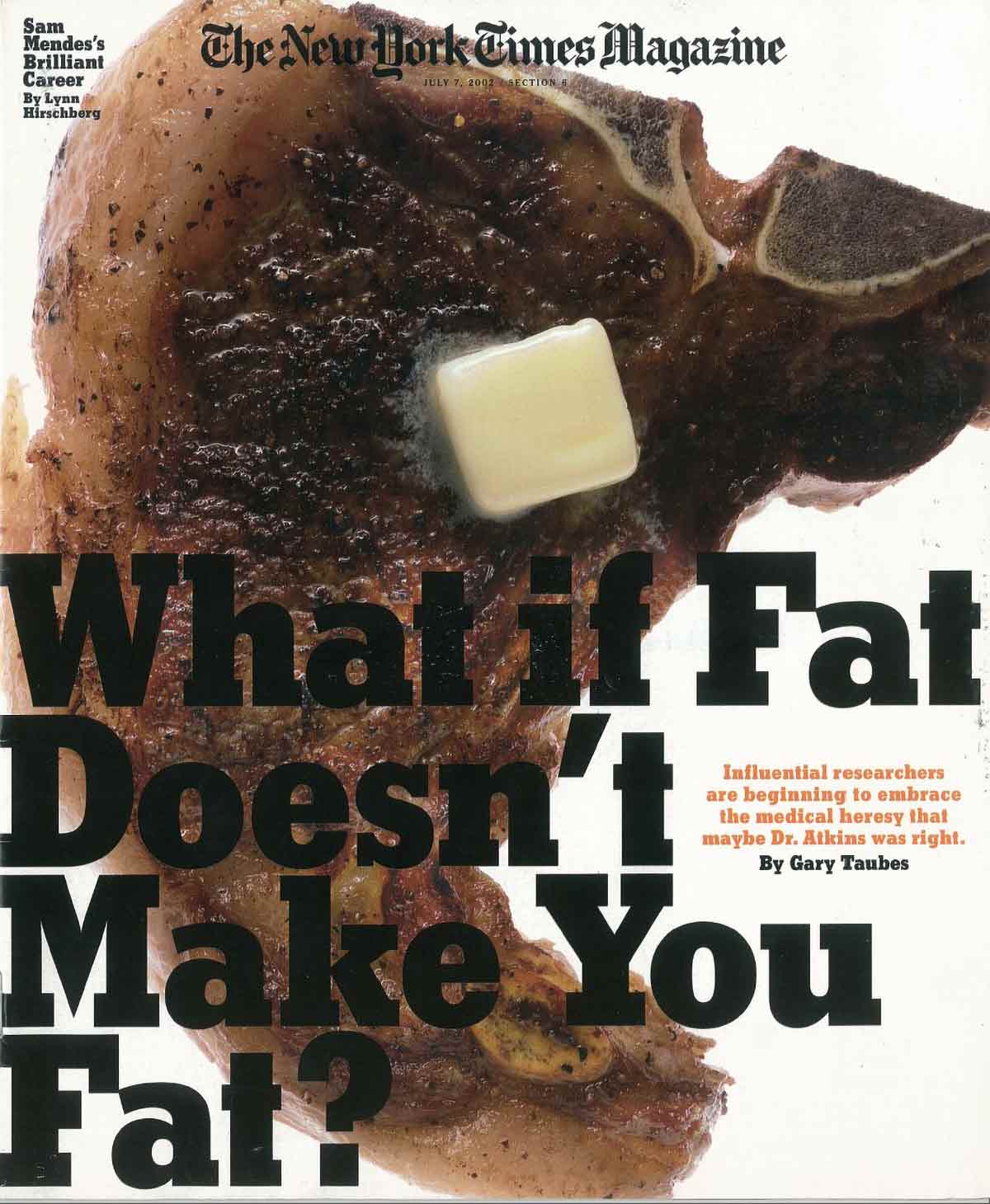

Gary: So what happened, when we decided that—that is, when the nutrition research and public health establishment decided that dietary fat was the cause of heart disease—they basically told the country that it was okay to eat as many carbs as you want, because carbs are heart healthy. In fact, they even assumed, without ever testing it, that somehow eating carbs would make you lose weight. So you took this dogma that every woman knew carbohydrates were fattening and you turned it into, “Every woman and every man should be eating carbohydrates to minimize fat accumulation.” It happened to coincide with an obesity epidemic and a diabetes epidemic. So I wrote an infamous The New York Times Magazine cover story on this.

David: Yes, yes.

Gary: The cover picture was the greasiest porterhouse steak they could find with a pat of butter on it, and the headline was, “What if fat doesn’t make you fat?” The subtitle could have been, “What if carbs do?”

David: Yeah.

Gary: That got me a big book advance, as infamous The New York Times Magazine cover stories will, and that allowed me to spend five years doing more research on this than any human being had ever done, quite literally. The result was my first book, Good Calories, Bad Calories. I’ve been unpacking the research in that ever since, but the one implication is that those of us who fatten easily—not everyone does, some people stay lean effortlessly—but those of us who fatten easily, the link is through carbohydrates. If you minimize your carbohydrate consumption, if you rigorously abstain from carbs, you’re basically eating a ketogenic diet, hence The Case for Keto.

David: So for those who don’t know, can you define exactly what a keto diet is?

Gary: Technically, keto is a diet in which you’re eating so few carbohydrates that your liver is synthesizing what are called ketone bodies. Now let me unpack that statement. The fundamental assumption we’re dealing with here, again, is that carbohydrates are fattening, and they do it not because of the calories involved, and we’ll have to discuss this, but because of the influence on the hormones that regulate fat accumulation, primarily insulin.

If you care about the textbook medicine, the accepted wisdom on the regulation of fat accumulation, then you want to minimize your fat accumulation, you want to minimize insulin secretion. If you minimize insulin secretion, you will be liberating fat from your fat cells, your liver cells will be converting that fat into ketones, and the ketones will be fueling your brain in place of the glucose that it normally uses or that it uses when you’re eating a carb-rich diet.

So a ketogenic diet is a diet that minimizes carbs and replaces those calories primarily with fat. If you do that, you will be in ketosis, your liver will be synthesizing these ketones, and in theory, all kinds of good things will now start happening.

Renee: Where did this approach, this relatively heretical idea, come from?

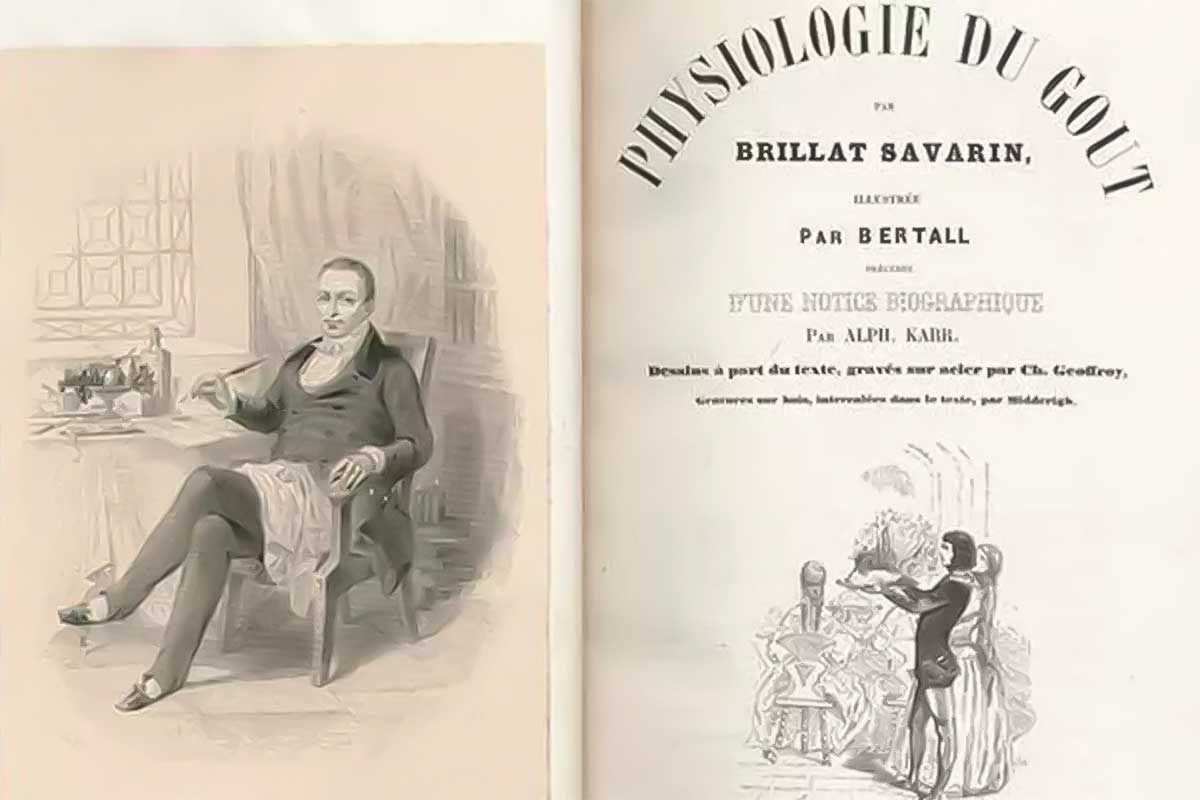

Gary: Well, this heretical idea was first voiced in 1825 in the most famous book ever written about food, The Physiology of Taste by Jean Anthelme Brillat-Savarin, which has been in print since 1825. I don’t think too many nonfiction books, other than the bible, can make that claim. Brillat-Savarin talked about this. He said, “I had interviews with 500 people, obese people over the course of the last 20 years, and invariably they told me that they couldn’t live without potatoes or bread or rice or pasta.” He said, “Animals get fat when you feed them carbohydrates and carnivores never get fat, so my hypothesis of obesity is that it’s caused by the carbohydrate content of the diet.”

He called it “farinaceous foods” back then. Sugar makes it worse, sugar wasn’t that much of an issue in early 19th century, because it was hard to come by and it was expensive. Then he proposed more or less rigid abstinence from carbohydrates. By the end of the 19th century, carbohydrate-restricted diets of various flavors were the standard of care for the relatively rare condition of obesity throughout Europe. Again, it stayed this conventional wisdom through the 1960s. In the 1960s, Robert Atkins came along. Atkins was the first person to really focus on this idea that this was a ketogenic diet, that’s what Malcolm Gladwell would call his “patent claim.” So again, you completely restrict carbs, you’re generating ketones.

If you’re generating ketones, you can bet that you’re losing fat, because that’s a requirement for ketosis. So he had his readers test their ketone levels in their urine with ketone strips, and the medical research establishment didn’t like this and it didn’t like people pushing a high-fat, high-saturated fat diet as Atkins was, just as they were beginning to embrace this idea that dietary fat and saturated fat were the causes of heart disease. So Atkins made a significant amount of money selling his diet, at one point his book was the…

David: The Diet Revolution, right?

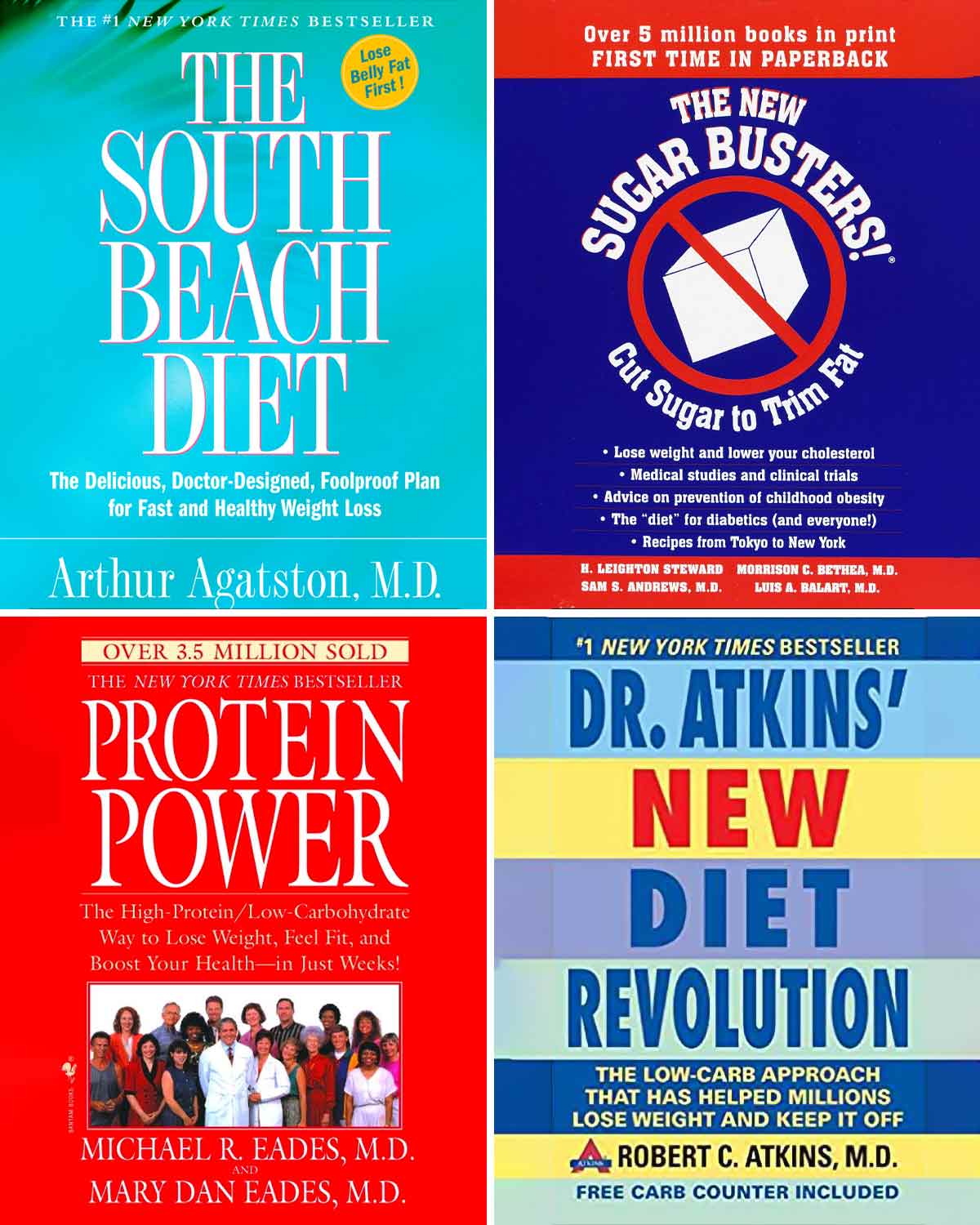

Gary: …The Atkins Diet Revolution sold more copies than the bible for one year, but Atkins was crucified. Ever after, the idea was if you were pushing anything like Atkins, you were a quack. So it never goes away though, physician after physician finds out that if he can get his patients to restrict carbs, he can get them to lose weight and then decides to write a book about it, but each physician has to bring a slightly different story.

Renee: Exactly.

Gary: They can’t push the fat like Atkins did, because if they do, they’ll be seen as either just like Atkins or promoting dangerous diets to their public. So you get things like Protein Power by Mike and Mary Eades, which is a very low-carbohydrate, relatively high-fat diet, but they focus on the protein. Or Sugar Busters by researchers at Tulane University in New Orleans, and you wouldn’t know from the title that this is very little different than Atkins. The South Beach Diet was designed by a cardiologist, a researcher physician in Miami who said, “Look, I was going to create an Atkins that was politically acceptable, so I was going to push the green vegetables in it and fish instead of red meat and dairy fats.” So you keep getting it. The diet never goes away because it works, and we can define what we mean by that.

Will cutting carbs help my health?

David: Let’s talk about the health benefits and what are perceived as the health liabilities of the diet. What are the things that can help people by going on keto? Besides losing weight, obviously. I’ve lost 60 pounds on keto, I’ve lost it before, but I’ve gained it back, which we’ll talk about in a little bit, too.

Gary: Part of what I’ve had to do in the course of my research is rethink a lot of fundamental assumptions of the nutrition and obesity research establishment as just wrong. A lot of it’s so naïve that it’s bizarrely wrong. For instance, the fundamental assumption is that obesity is caused by consuming more energy than you expend. So what that implies, David, is the reason you struggled with obesity your whole life, maybe more so than some of your friends growing up who didn’t struggle, is because you ate too much and they didn’t. That’s the only difference.

David: Yes.

Gary: There’s no physiological difference. And if you believe that obesity is all about this caloric balance instead of fundamental hormonal phenomenon in the body that are driving you to accumulate fat in a way that your lean friends’ bodies weren’t, if you think it’s all about energy balance, then diets work when they get you to eat less.

David: Yeah.

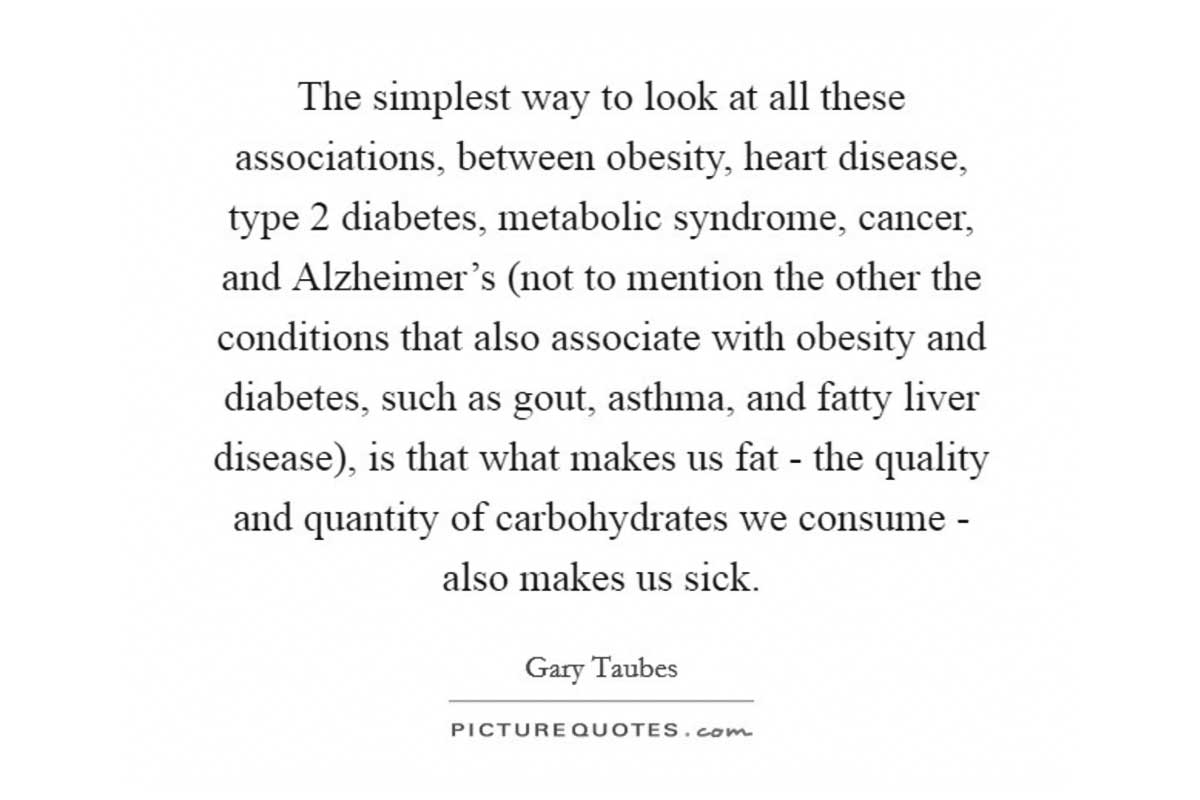

Gary: You can eat less on any diet. You’ll hear a common phrase that gets repeated over and over again in diet stories is “The diet that works is the one that you’ll stick to.” So now they don’t even define weight loss as an end prize, a definition of whether it works, or improved heart disease risk factors. If you stick to it, it’s working, and your doctors are happy. And, to the point of absurdity, so is the American Diabetes Association. One of the related concepts in all this is that type-2 diabetes and obesity are very closely associated, so much so that they’ve always been seen as two sides to the same disorder. We know that type-2 diabetes is an insulin-signaling disorder and a disorder of insulin resistance, and throughout the history of diabetes and diabetes treatment, the idea has always been that it’s a disorder of carbohydrate intolerance. You can’t tolerate the carbs in your diet, so for a very long time people said, “Well then, just don’t eat them.”

Gary: Then insulin came along and then suddenly you needed carbs to balance out the insulin that people were getting, and by the 1940s or so, physicians are saying, “Look, our patients don’t want to go on diets, let’s just let them eat whatever they want and cover it with insulin.”

David: Yep, absolutely.

Gary: Then the idea comes along that dietary fat causes heart disease and now the whole country’s being told to eat carbs, so the diabetics are told to eat more carbs and cover it with more insulin. So the latest document from the American Diabetes Association, which was published in 2019, tells doctors, “Tell your patients they can eat as much carbohydrates as they’ve always eaten, because they’re going to do that anyway, and if you tell them to do that, you can have faith that they’ll follow your advice.”

David: Yeah, interesting.

Renee: Wow.

Gary: I would like to think that this kind of Alice-in-Wonderland logic is me joking, and it’s not.

So again, there’s all these bizarre concepts that have been created by a research community, nutrition obesity researchers primarily, who have been so confused about the cause of obesity that they’ve had to adopt one irrational concept after another in order to defend their belief system. So to me, getting back to what does it mean for a diet to work, you can lose weight without being hungry.

David: Yes.

Gary: You’ll get healthier. We can tell you’re getting healthier, because we can measure all your heart disease risk factors, and there are, I don’t know, easily 26. I can guarantee there are 26 we can measure, and I can pretty much guarantee that at least 22 of them will get better.

David: What are some of those 22?

Gary: Well, your weight’s going down. Weight is the most significant risk factor. Your HDL cholesterol, the good cholesterol, will go up, and I’m pretty confident that it has gone up, and your triglycerides, which are a risk factor, will come down, which means your risk for heart disease and your blood pressure will come down. Your blood sugar will be under better control, by definition, because you’re not eating carbohydrates. There are all kinds of other inflammatory markers, other lipid markers that are more obscure, all of those will get better.

David: I can say that for me, so far with the 60 pounds that I’ve lost, of course I’m lighter, they cut my blood pressure medication in half, I have less pain in my joints, of course, which could just be structural, but I think it might also be some inflammatory markers, and I also have, because of Lyme disease, peripheral neuropathy in my feet. I notice that when I’m on keto, I really don’t have that same burning and pain in my feet. It’s not diabetic neuropathy, because I don’t have diabetes, my A1C is perfect, but when I’m on it, I don’t have the same pain.

Gary: One of the things I did for my new book, for The Case for Keto, is I interviewed 120-plus physicians around the world who had, for lack of a better word, converted to thinking the way I think. They believe the best thing they could do for their patients is to get their patients off these carbohydrate-rich foods, sugars, starches, grains, and eating like they do.

So one of them, a South African physician named Martin Andreas, working outside of Vancouver, Canada. said, “Put it this way,” and I thought it was very well put, he said, “For 50 years, we’ve been told to prescribe diets by hypothesis. We have this hypothesis that we should eat low-fat diets, mostly plants, we should calorie restrict if we’re overweight, and this will reduce our risk of heart disease and make us live longer.”

Gary: This is what we should tell our patients to do, but we have no idea whether it works. If our patients live to 70, if they live to 90, if they die a week later, you have no idea what the diet did for them. You might be able to measure a change in LDL cholesterol, but that’s it. So it’s purely prescribing by hypothesis. David, when you talk to your doctors and they get nervous and say, “Oh, you should be eating a plant-based diet.” A plant-based diet, the hypothesis is if you eat that, you will be healthier and you will live longer. On the flip side is diet by clinical experience, I can put a patient or myself on a low-carb, high-fat keto diet and watch them get healthier.

Gary: Their weight comes down, their blood pressure comes under control, their blood sugar comes under control, their A1C normalizes, their diabetic or non-diabetic neuropathy goes away, and they have more energy, their acne clears up. You name it. I can actually watch them get healthier.

What about the long-term effects of keto?

Renee: But what about the long-term effects of keto? No one, I don’t think, is disputing all these amazing things that can happen when you shift from a too-carbohydrate heavy diet. But what about the long term? Do these gains last?

Gary: Okay, so this is again, a couple of ways to answer that. One is the hypothesis underlying all this is that we get fat and we get sick because of the carbohydrate content in our diet. Some of us can tolerate it, just like some people can tolerate smoking cigarettes and live to be 110, we all know people who could eat all the carbs they want and they stay lean and they apparently stay healthy, but we can’t. That’s the idea, we’re different. Our bodies don’t tolerate it, so if we want to be healthy, we can’t eat those foods. So it’s pretty much that simple.

The simplistic analogy I use in the book is I have a corn allergy, so when I was a kid, I had GI problems all the time, cramps and worse, and my mother took me off to the doctor and we got an allergy test and he said, “You’re allergic to corn.” And I stopped eating corn. If I eat corn, the same problems occur at 64 that occurred at four, there’s just no way to get around it. So that’s one answer to your question, maybe we won’t live as long as ideally, we don’t know. The other is something I brought up when I was telling how I got into this. When we’re asking about the long-term effects of a diet, we’re asking, “Are we going to die prematurely, are we going to increase our chronic disease risk? Are we more likely to become diabetic or get heart disease or cancer or Alzheimer’s or pick-your-demise?”

The way you test that is you’ve got these chronic diseases that take years and decades to manifest themselves, we don’t really care whether the diet makes laboratory mice or rats live longer, we want to know if it makes us live longer. So you have to do these clinical trials where you randomize, say, a few tens of thousands of subjects to one dietary approach versus another. Then you follow them, you keep them on the diets and you have to follow them for five, 10, 20 years, and those trials have never been done. So we don’t know. You’re told to eat the Mediterranean Diet for instance, or a Dash Diet, which is one of the U.S. News & World Report’s favorite diets.

So they don’t know, either, and when, like I said, the whole country was put on a low-fat, low-salt diet in the 1980s, a concerted government program to get us to eat less fat, it coincided with increases in obesity and diabetes. That’s what got me into this field.

All we know is that you go on these low-carb diets, in the short run, you will get healthier, and because going on the diet means not eating the foods that make you sick, the assumption is if you continue to not eat the foods that make you sick, you will stay healthy. We don’t know, you may drop dead at any moment.

David: Well, any of us could drop dead.

Gary: If I did drop dead while talking to you guys, we still wouldn’t know, did the diet keep me alive 10 years longer than it otherwise would have? Would I normally have dropped dead in 2011?

David: But your doctors haven’t seen any kind of creeping up of your blood pressure, of your cholesterol, obviously not your weight, but have they seen worsening markers over those 20 years?

Gary: Well, I don’t get consistent tests, because the marker that they care about is LDL cholesterol, which mine is bad, by the way. We can talk endlessly about LDL cholesterol. I’m 30 pounds lighter than my heaviest weight, I maintain pretty effortlessly a 30-pound weight loss, which is supposed to be one of the hardest things to ever do in life, but those people who eat the way I do find it easy.

Can keto help make weight loss last?

Renee: Can I ask you a question about people finding it easy? The last statistic I saw indicated something like 98% of people who start a diet drop it at some point and regain the weight. You seem to be an exception in terms of having weight loss last that long.

Gary: Yeah, that’s quite possible. People think of diets as something you go on, you lose the weight, you go off. When I first started my research on this back in the early 2000s, I would often hear people say, “Oh yeah, I went on Atkins and just failed.” I say, “What do you by fail?” And they say, “Well, I lost 60 pounds, but then I gained it back.”

David: Right.

Gary: I said, “Well, did you stay on Atkins?” And they said, “No.” Then Atkins didn’t fail. So again, it’s a different way of thinking. If your idea is a diet has to make you eat less to maintain your weight loss and the weight comes back, the assumption is it failed to make you eat less.

Keto is saying carbohydrates are the problem, we can’t eat them. So it’s like saying most people who quit smoking fail numerous times before they eventually succeed, then as David knows, I’ll bring up smoking a lot as a metaphor. We know that smoking causes lung cancer and we just tell them to quit, and we know it’s difficult and we do everything we can to help them.

So one of the purposes of my writing these books is to get funding, in fact, for this hypothesis that I think is very compelling and very well supported by the evidence, that carbohydrates are the problem, particularly refined grains and sugars, including sugary beverages. If we could establish that they really are uniquely fattening—independent of calorie per calorie, that carbohydrates will make you fat when protein and fat will not—then it tells you what you have to do if you don’t want to suffer from obesity or diabetes.

It may not fix everyone.

How to combat “fat fatigue”

David: Yeah, but these people who are going up and down in weight, and I include myself, I did lose weight by basically starving myself at one point, which I think falls into the fasting element, and I lost 70 pounds, I kept it off about 10 years, but there’s been yo-yo dieting the rest of my life. One of the things I found on keto prior is that I got fat fatigue, I just didn’t want to eat all that fat anymore. How do you avoid or how do you combat fat fatigue?

Gary: Well, it depends. One way to do it is to adapt intermittent fasting. So if you’re not interested in eating fat, don’t eat at all, because your options are pretty slim now. So you could argue, “I got fat fatigue,” which means “I really wanted to eat a potato chip or I-don’t-know-what.” So the question is, what did you want to eat instead? If you didn’t want to eat anything instead, then skip a meal. This is the whole logic behind intermittent fasting or time-restricted eating. When you mentioned I didn’t eat breakfast with you that morning, that’s because about five years ago now, I stopped eating breakfast. I’m perfectly happy not eating until lunch and I don’t even know if my lunches are high fat anymore. You asked what I had for lunch, it was a restaurant around the corner that has a delicious chicken salad with grapes in it.

David: That’s not keto.

Gary: It is not keto, and for all I know, for the three months I’ve been living on this stuff, I may have been getting fatter, I should probably check. At some point, it will get noticeable. So once you get down to a weight that you’re comfortable with, if you start compromising now, you may never know what weight you would stabilize at without carbs in the diet. So you could think of it the way geneticists would talk about it, they say there’s this obese diabetic phenotype that’s triggered by the environment. So you have a certain genotype—David, yours is probably worse than ours in terms of fat accumulation—and then this carb-rich environment triggers it and the result is you manifest this obese phenotype. So the question is, what would your body be like in a carb-poor environment?

David: Yeah.

Gary: So the answer is, my guess is, you could lose 200 pounds.

David: Well, I need to. Not 200 anymore, but I did need to lose that much. One of the things I notice is that when I am on this modified keto that I’m on—it’s medically supervised, but it’s a modified keto—my cravings are gone, this horrible binge eating that I would do, in which I would go from sweet to salty and sweet to salty, are gone. I couldn’t stop no matter what, I tried, I could not stop. I don’t have those nagging cravings anymore, I can actually work all day long and not be thinking about what’s calling out my name in the refrigerator or the cabinet.

That, to me, is a huge relief, and then at the end of the day, which it’s always after dinner where it’s always the worst, I’m sitting there going, “Hmm, I really could have something to eat, but I don’t want to.” That is an amazing, amazing experience and I’ve never had that on any other diet, I must say. Weight Watchers didn’t do it, Jenny Craig didn’t do it, none of them did it.

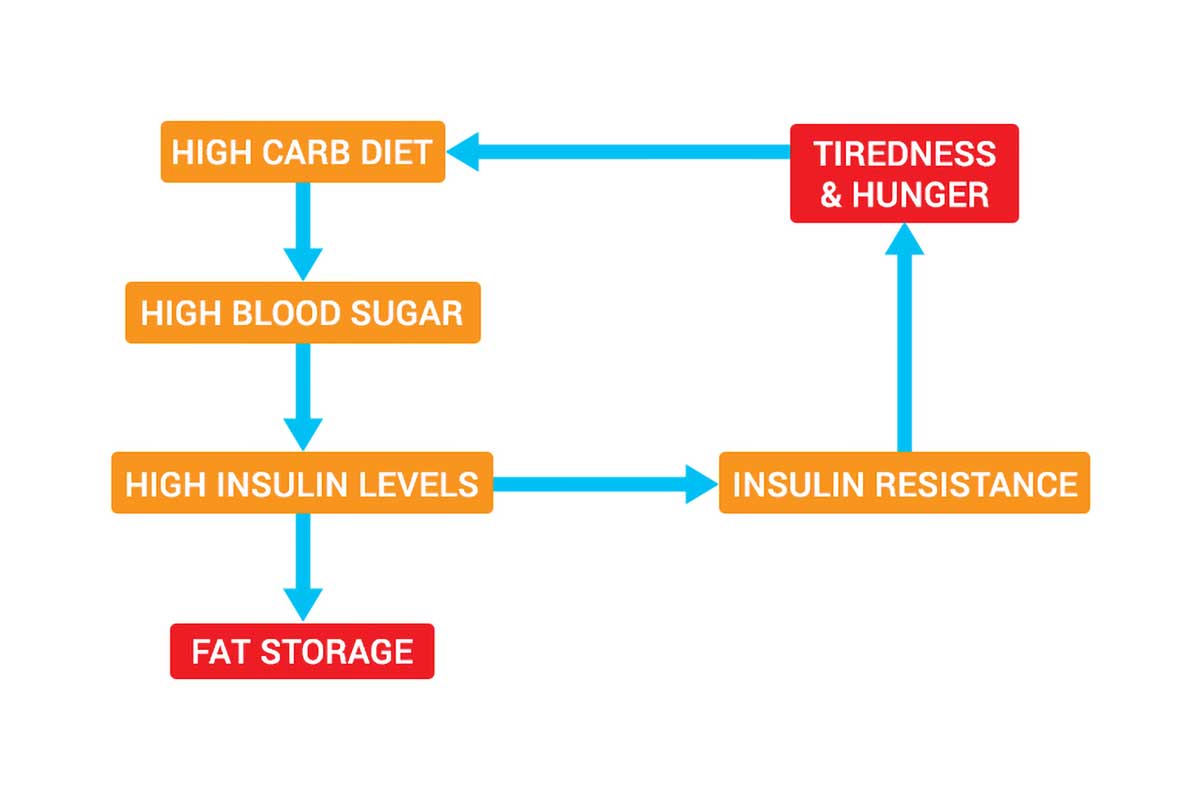

Gary: So the idea, again, is because when I say carbohydrates are fattening, it’s mediated primarily through the hormone insulin. Again, this is textbook science, it was worked out between the 1930s and the 1960s and it was not considered relevant to obesity, which is insane. But the researchers figured out how fat accumulation and fat cells are regulated and the hormone insulin—we secret insulin in response to the carbohydrates we eat—the medical community has always thought of it as insulin’s job to stimulate your tissues to keep blood sugar under control, because that’s what’s dysfunctional in diabetes, but one way it does that is by telling your fat tissue to hold onto fat.

So if insulin’s elevated, your fat tissue is holding onto fat. Without insulin getting as low as it can be, your fat tissue can’t mobilize that fat, and so your lean tissue can’t burn it for fuel.

If you don’t mind me asking, was your HDL low and your triglycerides high in your previous existence?

David: Yeah, HDL was low, LDL was really high, and triglycerides were really high.

Gary: Yeah. So you had what’s called metabolic syndrome.

David: Absolutely.

Gary: Metabolic syndrome is an insulin resistance syndrome, so that means your lean tissue is resistant to insulin, your pancreas is oversecreting insulin to do the job of trying to control your blood sugar, and it was succeeding, because your A1C was low.

David: Yes.

Gary: But it meant that there was always insulin, elevated levels of insulin, in your circulation, and so you’re always in fat storage mode. That’s what your insulin is telling your fat cells, just as caveats, this is the hypothesis behind the ketogenic diet based on textbook medicine. So now you lower insulin, you can mobilize fat from your fat tissue and your lean tissue can burn it for fuel. So in effect, when you say you lost 60 pounds, that means your body ate 60 pounds of your fat…

David: I know.

Gary: …that it didn’t eat when you were weight stable. That’s why you’re not hungry, by this thinking.

David: Yeah.

Gary: Okay? So you’re not thinking about food all the time, because the cells in what’s called the periphery, below your neck, are perfectly happy burning the fat that you’ve stored over your entire life in excess.

David: And I’m very happy that they’re burning it too.

Gary: Exactly, that’s exactly what you want it to do. So when you do a ketogenic diet or some variation on it, you’re basically allowing your body to work the way lean people’s bodies work naturally. Okay?

Renee: And we like that.

Gary: Yeah. That’s the reason I’m on your show and the reason I wrote this book is because no matter how much we love food, and we all do, those of us who fatten easily, to use this 1950s era diet book terminology, we just may have to avoid carbs. So we may have to learn to do our baking with almond flour.

David: Yeah. But don’t you sometimes feel like you’re King Lear howling into the wind on the heath with all of this?

Gary: Luckily, I’m not alone anymore, but being the guy who is arguing that the entire medical research community got it wrong at this level of screw up, on one hand, it gives my life meaning. It’s terrific. I joke that Don Quixote is my role model, or Sisyphus, depending on how I feel that day.

David: Yes, Sisyphus.

Gary: On the other hand, it just gets very weird. Yeah, you’re trying desperately to get people to pay attention. I’ll give you an example, I spent the winter working on an article for The New York Times Magazine explaining where we got this idea that obesity is caused by eating too much, what the counter argument was, who was promoting the counter hypothesis, and why this idea won out, the eating too much idea, despite the crazy naivety of it, and the implications on the obesity research community ever since. I handed in the article on March 14th and The Times paid for it, but the East Coast shut down around March 16th, and for nine months nobody was doing anything other than writing about COVID, vaccines, politics, and Black Lives protests.

The Times paid for the article, but finally they killed it, because the world has changed. They don’t want a journalist arguing that medical researchers could make a mistake of this magnitude, and I don’t blame them. I would have made the same decision. Then I sent it to The Atlantic, and The Atlantic, after a month said, “This is really interesting and strongly compelling, and it’s just too much for us to deal with in an era where we’re trying to get people to understand COVID and vaccines and whatever’s going on in the world in politics and the racial issues.”

To me, it’s the most important article I’ve ever written. As long as we believe obesity is caused by eating too much, people who are obese will be fat shamed and they will be given the wrong advice for how to fix it.

David: Yes.

Gary: They may never know whether it’s fixable, because they’ll never get the right advice and then they’ll never be able to understand it. I could be a quack, actually my friends say I can’t be a quack, because I’m not a doctor, so the best I could aspire to be is a whack job.

Is it easier for some people to lose weight than others?

Renee: The thing is, you’re telling people both exactly what they want to hear, but also not what they want to hear. They want to hear there’s an answer, but they don’t want the extreme solution that I think keto provides.

Gary: Well, also you’re telling people the exact opposite of what the public health advice for a healthy diet …

Renee: For years, yeah.

Gary: You even tell people to oversalt their foods on these diets to replace the electrolytes you’re losing when you don’t eat carbs. So there’s a cosmic joke in all this, but unfortunately, the people who pay the price are the ones who suffer from obesity, not those who don’t. The ones giving diet advice are the ones who don’t. That’s one of the points I make in the book, which is lean people think they don’t know what it means to struggle with their weight.

Renee: I’m going to jump in there and contest that.

David: As a lean person, as a lean person…

Renee: As a lean person. David doesn’t know my struggles with weight. He doesn’t know that I am careful about my carbs. I was keto-ish for decades, actually, and then I started to eat more carbs because I had to, because I couldn’t think clearly.

David: This is curious.

Renee: So maybe I am graced with better genes, maybe my activity level is stronger than David’s, there’s a lot of different factors that play into the difference between how I metabolize and you, Gary, and you, David. I have sympathy for people who have weight issues, because I do know how you’re treated in this society and it is shaming and it is awful…

David: Yes, it is.

Renee: …but it’s not always easy for someone just because that someone appears thin.

Gary: No, that’s true. Not always.

David: But Gary, can you explain though why, when Renee who is slender and thin and very fit, she’s like Miss Yoga, when she eats carbs, she feels less foggy. When I eat carbs, I just fall into the fog pit.

Gary: The answer is, I don’t know.

David: That’s fair.

Gary: It’s funny, because I’ve been in a brain fog my whole life, and I would blame it on my diet, except that I was writing articles about being burnt out when I was 28 years old. One of the things that I argue in this book and that people in my world argue is that this is all about self experimentation on some point. So for instance, what you did, Renee, is you realized when you ate more carbs, your brain is clearer and maybe you sacrificed a few pounds of weight for cognitive clarity.

Renee: Exactly.

Gary: I experimented with various things and last year, I was lecturing in Australia, I had cramps. Ccramps are often a problem on these low-carb, high-fat ketogenic diets, and they seem to be due to electrolyte loss and they can be replaced by supplementing sodium and magnesium and sometimes potassium. I was talking to a nutritionist in Australia complaining about the cramps, and we were with a British diabetes specialist, and they both said, “You’ve got to take more magnesium.” I said, “How do I know when I’ve had enough?” They said, “When you stop cramping.” I upped the magnesium, I Googled to make sure I can’t magnesium overdoes, and I stopped cramping and my brain fog went away.

David: Interesting.

Gary: So was it electrolytes for me? I don’t know if it’s going to stay away, for all I know, by tomorrow, I’ll be back in a brain fog. Who knows? One of the reasons I continued with intermittent fasting, not eating breakfast, is I found my brain was much sharper in the mornings when I didn’t eat, even though all I was eating was eggs and bacon. So there are various things, basically. Once you do the major fixes on your diet, which are getting rid of sugars and sugary beverages and beer, unfortunately…

Renee: Unfortunately.

Gary: Yeah. The highly refined grains and starchy vegetables like potatoes, and you start playing around to see what works and what doesn’t. The same thing you would do if you had allergies and you were trying to identify what the allergy is, these isolation diets.

Renee: Yes. It’s very bioindividualistic. I’ve done those elimination diets to determine possible allergies, and they can be maddening as they take a lot of time. I think the trick is with keto and Americans, we’re impatient. I think a lot of people want a quick fix and they want definite answers.

Gary: Yeah, absolutely. First of all, this is a quick fix. The problem is that a lot of people don’t want to. You have to understand why you’re doing it and what you’re doing it for if you’re not going to eat a cinnamon bun ever again. I think on my death bed, if Hal’s still exists in Venice Beach, in California, I will have somebody send me their rice pudding.

Renee: Nice.

Gary: I get it, but on the other hand, I used to love smoking cigarettes. Cigarettes used to be my life, I looked forward to my next cigarette, I got out of bed because that meant in an hour I would have my next cigarette after my first cup of coffee. I quit because I was fairly confident it was going to shorten my life, and I also had, I still have to clear my throat all the time, and I haven’t smoked in 20 years. I don’t miss them. It wasn’t a quick fix, it wasn’t easy. I had to try four or five times before I succeeded. I’m still tempted on occasions, and you couldn’t pay me to go back.

David: Well, it’s interesting, in researching for this interview I went on a lot of keto boards and in a lot of keto groups, and this one person said something fascinating. She said, “It’s just like quitting smoking, you have to keep trying until it actually sticks.” Very few people out of the gate try keto, lose the weight, their life has changed. You have to keep on trying it. This may be the time that works for me. I hope it does.

Gary: I wrote this book to give people, first of all, the confidence that doing this should make you healthier. There’s every reason to believe this will make you healthier and you could quantify that, but to understand it, to understand how best to do it, to understand why you’re doing it, and to give yourself the best chance of succeeding out of the gate. So if it’s true and you eventually have to quit carbs to achieve and maintain a healthy weight, we don’t know what a healthy weight for anyone is, but if that’s our goal, and assuming you’re at a healthy weight, you will feel your best, you’ll have the most energy and the fewest chronic disease risk factors by definition, then you’ve got to understand how to do this right and give it a shot.

Because clearly, for an enormous number of people, it helps them. You’re right, probably a small percentage of all the people who try, Atkins probably sold 20 million books, or 30 million books, since it was first published in 1972, and I very much doubt there are 30 million people on Atkins still. But ultimately, what you’re sustaining is how good you feel. So you understand that the carbs are the problem the way I understand cigarettes were the problem, and I don’t want to increase my risk of lung cancer, I don’t want to wake up at 3:00 in the morning with that horrible taste in my mouth, coughing and sounding like my father. I already look like my father, do I have to sound like he did? Then the other flip side with this is because you’re basically, what you’re doing, what David has done is he switched his body from burning carbs for fuel to burning fat for fuel.

The reason why you would have been hungry all the time and had these food binges, because when you’re burning carbs for fuel and your insulin’s elevated, as you start to burn through the carbs, you can access your fat, so now you just get hungry and if insulin’s elevated, carbohydrates are your fuel. That’s the only thing your cells will burn, so now you crave carb-rich foods and sweets.

Renee: It’s a vicious cycle.

Gary: There’s a cycle, so you switch to fat-rich foods, and this was demonstrated in animals in the 1930s, now you start to crave fat-rich foods.

The case for fat over protein

Renee: Does it have to be fat? Can you replace the carbs with protein?

Gary: It gets tricky. So think about what it means to replace the carbs with protein. Protein tends to come with fat attached, for starters. A classic way to do this, because people want a compromise, so they say, “Well, maybe Taubes and all those doctors and researchers are right and carbs are a problem, but clearly those other people couldn’t have been all wrong, so I’m going to hedge my bets and eat a low-carb, high-protein diet.”

David: Yes, and a lot of medical facilities and hospitals use that model for their weight loss programs.

Gary: Right. So now you’re getting green leafy vegetables and a skinless chicken breast, and as far as I’m concerned, a skinless chicken breast, just culinarily speaking, let’s be serious, the only way to make it edible is to either marinate it some sugar or soy concoction, so you’re adding carbs back, or to bread it with carbs. Right?

David: Right.

Gary: Here’s the biological logic against it. Now, one of the doctors I respect in this business is a Seattle physician named Ted Naiman, who has got to stop putting up Twitter photos of his muscular upper body without a shirt on doing pull-ups, but other than that, he’s a smart guy. He believes that these diets should be high protein. I respect Ted, the way he thinks, maybe he’s right. Everyone else, most other people think they have to be high fat. The logic behind it is you’re trying to minimize insulin secretion, okay? Protein, some numbers I read recently, 58%, 60% of the amino acids in protein are converted into glucose and they stimulate insulin secretion. Now, protein also stimulates a counter-regulatory hormone called glucagon, which is a good thing, it works against insulin in the fat tissue and it will stimulate growth hormone secretion, which is a good thing. But if you have to minimize insulin, you need fat, not protein.

Renee: Interesting.

Gary: So for somebody whose fat cells are really insulin sensitive, as I’m willing to bet David’s are and were, even if you try to replace those calories with protein, you’re going to stimulate some insulin. Now the other way to think about it is you could calorie restrict and use protein, so now you’re not going to get as much insulin secretion, but now you’re going to be hungrier. Okay? Part of the goal is to allow you to eat to satiety. What’s interesting, my next book is going to be on diabetes, so I’ve been reading all the literature on diabetes going back to the 19th century, and they had the exact same debate about diabetes in the six years before insulin was discovered.

The question, is it the calories or the carbohydrates? We can restrict the carbohydrates, but some people go into a coma and then it turned out that maybe part of the problem was that they’re being fed too much protein. So if you restrict carbs and protein and replace it with fat, you’re in much better shape. I use a lot of butter and I use a lot of olive oil, again, maybe I’m going to have a heart attack any second, no guarantees.

David: That’s not a good advertisement for your book when you keep saying that!

Renee: Like you, I love fat…

David: She does.

Renee: …I love salt and pepper rib-eyes, give me pork butt. Of course, grass-fed when possible, so it’s all the healthful fats. So I believe in fat and the power of fat and satiety, as well as just a role in a healthy diet, but is there a rough percentage for people who are looking to try this keto thing? What percentage of your diet do you want fat versus protein versus carb?

David: That’s a great question.

Gary: So that’s an obvious question, but I’m going to confuse it. When you eat a rib-eye, do you have any idea what percentage is protein and what is fat?

Renee: I don’t know. I just know it tastes damn good.

Gary: Exactly. Then again, it depends on how metabolically unhealthy you are, how much extra weight you’re carrying, and how bad your diabetes is.

Renee: There’s a ton of individual factors.

Gary: Yeah. So I don’t like to think in percentages. The nutrition community on my side of this fence will talk about the protein at 10% to 15% of calories, carbs as low as 5%, and the rest fat, so that’s 80% of calories. It might be 70% or 60% to 80% of calories from fat. If it’s 60%, that means you’re getting about 30% from protein, which is a high-protein diet, so now you’re moving towards skinless chicken breast land. I think the best advice is don’t eat these foods, and when I’ve been interviewing these doctors and asked them what the challenges were on these diets, the primary challenge was getting the patients to stop fearing the fat in their diets.

Renee: Right.

Gary: So instead of having a skinless chicken breast, have a chicken thigh, which is fatter, with the skin attached. Now you’re having a high-fat food, not a high-protein food. Instead of cutting the fat off your rib-eye or buying a lean cut of beef, which is sinful also, sinful in a bad way, not in a culinary way, just embrace the fat on the fish and the fowl and the meat that you’re eating.

If you’re doing that, if you have type-2 diabetes, then you might want to go so far, really up the fat intake, so now you’re really talking about putting extra fat, butter or olive oil, on the green vegetables you’re consuming. The smartest person I know in the diabetes world, she advises her patients to see green vegetables as a platform on which to put fat.

David: Oh, I like her.

Gary: But that’s it. I think if people start thinking in percentages, they’re going to confuse themselves. Don’t eat these foods, this is okay.

Renee: Great advice.

David: Well, Gary, we could talk about this forever. Maybe you can come back on the show after I’ve lost all the weight and we can do a catch-up. How’s that?

Gary: That would be great, although we have to talk about the calorie restriction you’re on.

David: We’ll talk about it.

Renee: Gary, thank you so much.

David: Thank you.

Gary: Okay, thank you, guys.

David: Gary Taubes has been writing about the science of weight loss for more than two decades. His latest book is the Case for Keto. You can find out more about Gary at GaryTaubes.com, as well as on Twitter @GaryTaubes. Ciao.

Renee: Ciao.