To understand the once-wholesale dismissal of American butter by many chefs requires a look back at two of the great watershed events in this country’s history: the world wars. According to Jonathan White, artisanal cheese maker and owner of Bobolink Dairy in Vernon, NJ, there was no such thing as 80 percent sweet-cream butter — the product today’s chefs find bland and watery — before the advent of refrigeration and industrialization.

“Because of smaller-scale production, butter was churned every second or third day, so the room-temperature cream had time to sour, or ferment,” he says. It was this cream, in essence crème fraîche, that was churned into a richer, more complex-tasting butter — the kind many of the best French dairies were producing. In the United States, the wars put an end to this process by drafting many of the young farmers and encouraging large companies to industrialize the dairy industry, in an effort to manufacture rations for troops and products for foreign-relief efforts. With the introduction of the continuous butter maker, it was possible to pour uncultured cream into one end and, minutes later, get butter with a consistent 20 percent water content out the other. The technology helped win the wars but killed the spirit of American butter.

So what has prompted highly regarded chefs — such as François Payard, owner of Payard Patisserie and Bistro, and Eric Bertoïa, executive pastry chef at Daniel, both in New York City, as well as Gregory Gourreau, executive pastry chef at Le Cirque in Las Vegas — to open their larders to American butters? In part, the reemergence of small, artisanal dairies. Says Allison Hooper, co-founder of the Vermont Butter & Cheese Company in Websterville, VT, “We looked around and saw that in order to make a niche for ourselves, we had to raise the butter bar.” She has done that by producing a cultured butter with an 86 percent butterfat content. Hooper’s company, along with other small producers, such as Ronnybrook Farm Dairy in Ancramdale, NY, and the Straus Family Creamery in Marshall, CA, was among the first to fill a nearly 90-year void.

“Only now can we find very good butter in America [like that] from small farms in upstate New York,” says Payard, referring to Ronnybrook Farms. “It’s very close to French butter.” Others agree. “Some American butters are very, very good,” says Michael Rispe, pastry chef at the Waldorf=Astoria in Manhattan. He uses the domestic brand Beuremont for many of his desserts, including Lemon Pound Cake. “I like the rich flavor and smooth, homogeneous consistency,” he adds. Bertoïa also uses Beuremont for pâte sablée, pâte brisée, tuiles and petits fours. Gourreau, on the other hand, prefers Anderson butter for many of his desserts. “Especially for chocolate ganache,” he says. “The butterfat content makes a smoother product.”

But the appearance of American butter in pastry kitchens isn’t solely the achievement of artisanal dairy producers. To compete with unsalted French butter, which by law requires a minimum of 82 percent butterfat versus 80 percent for American butter, a new wave of commercial American brands with a higher fat content has appeared. Ten-year-old Plugrá, which weighs in at 82 percent butterfat, is a favorite of many chefs. Priscilla Martel, chef-instructor at the Center for Culinary Arts in Cromwell, CT, uses an analogy to drive home the significance of the seemingly small increase in butterfat. “Is there a difference in taste between whole milk and 1 percent milk?” she asks. “Of course there is. It’s the same with butter. It really does add up.”

“The difference is not just the fat content, there’s also less liquid [in Plugrá],” says Pamela Fitzpatrick, executive baker at Fox & Obel Food Market in Chicago. “That extra percentage does so much for pastries and laminated doughs. But where I notice the difference is with bread and brioche. The butter is very plastic and incorporates into the dough beautifully.”

Payard, known for his passionate adherence to quality, also uses Plugrá. “It works very well for pastry,” he says. “But you have to know what to use when. There’s a big difference between using the right product and using the [best] product simply because it’s the best.”

Nearly every chef who was interviewed echoed his sentiment. Most agree they would reach for a French brand when an intense buttery taste was paramount, in a sablé Breton or a particularly delicate lemon curd, for example. But, for the most part, they prefer American butter for making items such as almond creams, ganaches and other fillings. Some, though, turn to American brands for the true test of a butter’s mettle: mille-feuille.

Pierre Hermé, pastry chef and owner of the patisserie Pierre Hermé in Paris, proved this point to himself when he was developing baked goods for the U.S. grocery chain Wegmans Food Market. “When we started to make croissants at Wegmans, we made some with French butter and some with American butter. The difference was amazing. The rise, taste and appearance were better with French butter. But for the puff pastry, we always use American butter.”

While most of the chefs agree that French butter is the answer when flavor truly matters, the accord stops there. There’s no consensus as to which brand is the best. For 15 years Hermé has used La Viette in his Paris shops, which is what has made his Lemon Cream Tart a best-seller for as long as any food critic can remember. Payard is partial to Lescure, as is Yvan Lemoine, pastry chef at Fleur de Sel in New York City. When asked why he prefers Lescure for his Caramelized Apple Crepes, Lemoine says, “It turns into a more intense, buttery caramel. It matters in the crepe batter, too. The crepes don’t dry out after they cook. They stay very moist.”

Gourreau prefers Échiré for his inside-out puff pastry, which he uses as a component for many of his desserts. “I like the flavor and the richness. It also gives a beautiful rise to the dough.” Bertoïa uses Échiré as well, mostly with chocolate and fruits, though he puts Montaigu to work in croissants and mille-feuille because it’s “very dry, drier than Échiré, so it makes great pastry.”

But this French-butter feeding frenzy among chefs can be misleading. The brands sitting on pastry tables in the finest restaurant kitchens represent a small percentage of the butters produced in France. “Right now, only 10 percent or 20 percent of French butter is any good,” remarks Rispe. “The remaining 80 percent is similar to America’s double-A butter. I believe the reason why people think French butter is the best is because they’ve only tasted that 20 percent.”

Regardless, this small percentage of butter is outstanding for good reason. “They’ve been making it [the same way] for many centuries, and they’ve got it down to a science,” comments Steven Jenkins, dairy buyer at Fairway Market in Manhattan and Plainview, NY. “On a scale of one to ten, it’s a ten-er.”

Because of the history and consistency of the production of these exclusive butters, nearly all of them fall under the designation of Appellation D’Origine Contrôlée (AOC). At the moment only a handful of areas in France, which include Charentes-Poitou and Normandy, produce AOC butter. The AOC requires that each butter’s character be rooted in a limited geographic domain. So the pastures where the cows graze, the feed they are given, and even the local springwater the farmers wash the butter with are carefully monitored. “It’s the quality of the land that makes French butter so good,” Bertoïa says. And it’s this inalienable French concept of terroir that many chefs, both French and American, use to draw a line in the sand.

Yet some believe that good land is good no matter where it is, and they argue that American butter, if carefully produced, can match or surpass French butter. “We have superior pastures, and we have superior animals,” Jenkins points out. “The result of that would make better butter, if we knew how to culture it properly.”

Hooper, whose butter is made from the milk of cows that graze on some of Vermont’s most verdant pastures, land reminiscent of France’s protected terroir, agrees. “The key to making superior American butter is in the culturing,” she says. “It’s what gives a longer, lingering flavor. When we were testing our butter, I gave some to a chef who was raised in Brittany. After tasting it, he said, ‘Don’t change a thing. It’s just like the butter I grew up eating.'”

Often, though, taste takes a backseat to cost. By definition AOC-butter production is small scale. “The [Échiré] cooperative produces 950 tons of butter each year, just 0.2 percent of all the butter produced in France annually,” wrote journalist and author Dorie Greenspan in a New York Times article last year. This limited supply creates a seller’s market, which ratchets up the butter’s price. “Butter is like Wall Street,” says Payard. “Prices go up and down. Sometimes if I get a good price, I’ll lock it in.” According to Hermé, some chefs even engage in butter speculation, hoping to get the best possible price. One solution they’ve found for keeping costs down, while sacrificing little or no quality, is adding commercial American butters, such Plugrá or Beuremont, to their inventory.

Surprisingly, it’s not just French butter that can burn a hole in a chef’s wallet. American butter has on occasion edged out its French rival when it comes to price. “Sometimes you’re better off buying French butter,” remarks Payard. “Two summers ago the price of American butter went sky high. Why? Because all the cream was being used for ice cream.” Instead, he ordered French butter at a lower price than he could get for domestic brands.

Despite all the posturing about the quality of French versus American butter, nothing can cause a chef to disregard personal preferences, transcend nationalism, and overlook cost faster than freshness. Chefs rely on it to give their pastries a competitive edge. Hermé prides himself on the freshness of the butter he uses. “When it’s delivered to me, it’s a maximum of seven days old,” he says. “Many times it’s four days, three days, even two days old. It’s not butter that was stored for months.”

Although some chefs freeze their butter, especially when they’ve purchased the lion’s share because they wrangled a low price, Hooper warns against this: “The butter’s structure changes. It doesn’t perform the same way; it doesn’t give the same lift to laminated doughs as it does when it’s fresh.”

Cheese maker Jonathan White cautions that some of the French butters, although at the peak of freshness when packaged, can sometimes taste old when they arrive in the United States. “It’s most likely by dint of how they were handled,” he says. “My recommendation? You want to get the freshest butter you can get, regardless of how it was made or where it was made. I’d rather have fresh Land O’Lakes than anybody’s old [AOC] butter.”

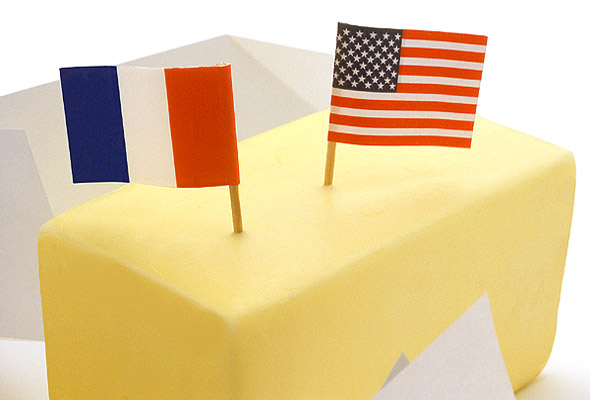

In the end, the 90-year-old stronghold that French butter has had over pastry kitchens seems to be loosening. Many chefs are accepting what American artisanal dairies have to offer, oftentimes collaborating with them to produce a meticulously cultured butter that, because of its American terroir, can rival some of France’s best. And ironically, French butter’s continued allure and status are assured by the addition of high-quality, less-expensive commercial American brands. This culinary détente, unimaginable just 12 years ago, is helping chefs turn out products of superb quality, consistently and economically.

Photo © 2003 George Jardine. All Rights reserved.