How did we in 10 decades go from gruel to Starbucks?

“Quickly,” says Melanie Barnard, a Bon Appétit columnist and author of Short & Sweet (Houghton Mifflin, 1999). “Changes to the food we’ve eaten started slowly but then went into fast forward, mirroring the times.”

This century, more than any other, has been one of staggering transformation. Our population has mushroomed by almost 200 million since 1900. Passenger travel zoomed from the horse to the supersonic. Computers accomplish in hours what took a turn-of-the-century factory crew days. And the foods we’ve eaten have taken an equally remarkable journey.

1900—1909

The 20th century was rung in with contagious optimism. As early as the mid-1890s it was dubbed the American Century. The consensus, at least at home, was that we were an unrivaled world power to whom the future belonged.

Such heady times required heady meals. From the denizens of Newport, Rhode Island’s multimillion-dollar cottages to knockabout American laborers, menus were meat-filled. New York City’s haute restaurants offered elk, caribou, bear, moose and even elephant to intrepid diners. Modest eating establishments in the Midwest served mountains of the same (minus the elephant), albeit with less fanfare and a considerably lower price tag.

A particular favorite along the eastern seaboard was Oysters Rockefeller — baked oysters topped with savory shredded greens. Although not a 20th-century dish by definition (it was invented in 1899 by Jules Alciatore of Antoine’s Restaurant in New Orleans), it reached its zenith in the early 1900s. Because of its rich ingredients, Alciatore chose John D. Rockefeller, one of the wealthiest men in the nation, as its namesake.

Alciatore also (deliberately?) shrouded his creation in mystery — an early and successful marketing coup. He emphatically insisted that the finely minced greens were not spinach, as was commonly assumed. Later his great-grandson, Roy F. Guste Jr., was equally tight-lipped in Antoine’s Restaurant Since 1840 Cookbook (W. W. Norton & Company, 1980). “The original recipe is still a secret that I will not divulge…If you care to concoct your version, I would tell you only that the sauce is basically a purée of a number of green vegetables other than spinach.”

But, as Bruce Kraig, professor of history at Roosevelt University and president of the Culinary Historians of Chicago, cautions, “it’s important to keep in mind that this kind of food was reserved for the wealthy and upper classes. The middle and lower classes ate far more humbly.”

One commodity that crossed class boundaries was sugar. By 1909, America had an aching sweet tooth, with the average person consuming 65 pounds of sugar annually. The culprits: chocolate brownies, apple pie, devil’s food cake and baked Alaska. Sweetened tea and coffee (and its newly invented decaf cousin) also contributed to our ancestors’ passion for sugar.

Recipe

1910—1919

Immigration was at an all-time high during these years, bringing new flavors to the kitchen. Italian, German, Jewish, Chinese and Eastern European foods filled millions of tables, mostly in ethnic enclaves in large cities. As a result the 1910s became the “hyphenate decade.” Merrill Shindler describes in American Dish (Angel City Press, 1996) how food descriptors such as Italian-American, Chinese-American and Jewish-American began popping up. Spaghetti and Meatballs, Chop Suey, Chow Mein, Swedish Meatballs and goulashes of every sort crowded specials boards in neighborhood restaurants.

In addition, says Kraig, the 1910s saw the beginning of the proliferation of processed foods. In a scant 10 years, Hellmann’s mayonnaise, Oreo cookies, Crisco, Quaker Puffed Wheat and Puffed Rice, Marshmallow Fluff and Nathan’s hot dogs took a bow. Aunt Jemima’s smile was already imprinted upon the American culinary psyche, as were the Kellogg’s and C.W. Post’s brand names. And lucky Clarence Birdseye — who on an ice-fishing trip noticed that a fish left out in the cold froze instantly and tasted good when cooked weeks later — set about perfecting his “Frosted Foods,” which he would introduce to the world in 1930.

We needed a place to purchase such bounty, and the self-service market was born. Instead of having to hand a list to a clerk and wait as he fetched the items from the back, a customer could amble through the shop’s aisles at her leisure. Stores such as A&P offered up to a thousand items (29,000 fewer than today’s supermarkets), boggling the minds of housewives everywhere.

With such variety and availability, the over-indulgence of the first decade prevailed — at least among the wealthy. Restaurant menus remained chockfull of meats, shellfish, pâtés and mousses, and the girth of the upper classes remained formidable. “Before World War I it was chic to look plump,” says Ruth Adams Bronz, author of Miss Ruby’s American Cooking (Harper & Row, 1989). “Round was in.” The poster boy of the times: our then president, William H. Taft, a hefty 300-pounder. Is it any wonder his favorite meal was Lobster Newburg?

A wildly popular dish of the day was Vichyssoise. Dreamed up in 1917 by Chef Louis Diat of New York City’s Ritz-Carlton Hotel, Vichyssoise is a heavenly chilled soup of puréed leeks, onions, potatoes and cream.

Vichyssoise’s enduring popularity has as much to do with its superb taste as with its relatively democratic ingredients. It could be made in the most well-to-do as well as the most simple of homes. Granted, leeks weren’t common at the time, but that wasn’t something a resourceful cook couldn’t fix with an extra onion or two.

A death knell sounded in January 1919, when the Eighteenth Amendment — otherwise known as Prohibition — was ratified. Scheduled to go into effect on January 16, 1920, Prohibition was going to save those poor souls whose moral compasses had gone awry. Or so self-satisfied politicians told one another over glasses of port after dinner.

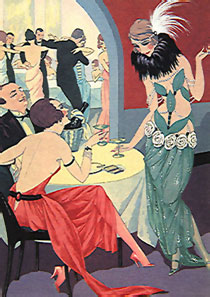

1920—1929

The Roaring Twenties were indeed a deafening decade. The music was loud, the people wild and the stock market boisterous. We had money and were willing to spend it in the most conspicuous ways. Novel electrical gadgets like toasters, refrigerators and gas stoves were being sold by the thousands. Maîtres d’hôtel (as in earlier decades, the best food was still found in hotels) were tripping over themselves to serve the most sumptuous and costly dishes.

The unwelcomed appearance of Prohibition did little to curtail the drinking habits of the masses. The Noble Experiment, as it was called, actually encouraged us to drink more, which is why in part it was repealed in 1933. In fact, the majority of the drinks we know today were concocted during Prohibition.

Speakeasies sprang up everywhere, and patrons slunk into these underground establishments by the millions to drink and to listen to the new music called jazz. To accommodate them, and to soak up some of the harsh bathtub gin, proprietors began offering finger foods. Delights such as Shrimp Patties, Oyster Cocktails and Mushrooms Stuffed With Pimientos filled makeshift bars. Customers brought the idea into their homes, and the cocktail party was born.

While the more affluent crowd sipped and chattered away at their parlor parties, the rest of us repaired to the dining room (or eat-in kitchen) for dinner. Something was missing from most tables, though. “Salads were considered effeminate and French,” says Krishnendu Ray, a food historian at The Culinary Institute of America in Hyde Park, New York. “They were looked upon with suspicion by conservative, middle-class Americans.” That, however, was soon to change.

On July 4, 1924, in Tijuana, Mexico, Caesar’s Place was packed with Hollywood folk who had headed south for the holiday to evade the restriction of Prohibition. By the end of the busy night, the kitchen was nearly empty except for a few ingredients — romaine lettuce, Romano cheese, bread, olive oil and some eggs. With these, proprietor Caesar Cardini whipped up the famous Caesar Salad.

Regarding the pomp of the salad’s tableside tossing, food columnist and cookbook author Arthur Schwartz wrote in a 1995 article for the New York Daily News that Cardini believed “give the show people a little show and they’ll never realize it’s only a salad.” He was right.

Word spread, and Hollywood swells and average joes flocked to Tijuana and sat elbow to elbow feasting on Cardini’s sensation and delighting in his peerless showmanship. Together with The Brown Derby’s Cobb Salad and the Palace Court’s Green Goddess Salad, the Caesar secured a place for salads on menus and tables across the country.

But the one item that best defines the 1920s is nether fish nor fowl nor leafy green. It’s the Martini. No sophisticate would dare be seen without a Martini nonchalantly cupped on one hand and a Camel cigarette cocked in the other.

The origin of the Martini remains unknown. Experts name several sources of pedigree, all of them happy to claim credit. Regardless of its heritage, what’s special about the shimmering, silvery Martini is its elegance. It was the perfect accessory for the slender flapper and the sleek Dapper Dan — the full-figured ideal of the previous decades disappeared, never to return.

No other cocktail has incited such passion or ire when it comes to the proper way to make one. Some, like the genetically cool James Bond, say it should be served “shaken, not stirred” so as not to “bruise the gin.” Somerset Maugham insisted that “martinis should always be stirred, not shaken, so that the molecules lie sensuously on top of one another.” Either way, the best Martini is always served ice-cold.

The decade’s giddiness from unprecedented wealth — and a surfeit of Martinis, no doubt — came to a gut-crushing halt on October 29, 1929, when the Dow Jones plummeted a then staggering 30.57 points.

1930—1939

Black Tuesday hurled America into the Great Depression for the better part of the 1930s. Families were now faced with the challenge of making due with less. The Depression was a great task master, forcing people to be thrifty and use every bit of food, ad every ounce of ingenuity, to stretch meals.

Menus were radically pared down, notes Ray. “Protein, which is always the most expensive part of the meal, had to be reduced.” He explains that, to compensate, “cooks tried to use other foods such as vegetables and beans as substitutes” — something the revised edition of Fannie Farmer’s Boston Cooking-School Cook Book (Little, Brown & Company, 1930) advocated.

Popular dishes of the period were inexpensive, one-pot meals such as macaroni and cheese, chili, oxtail soup, casseroles of all sorts and — to maintain the illusion of the abundance of beef — meat loaf, stretched to its limit with filler. Accompaniments were usually inexpensive vegetables such as carrots, peas and potatoes. City dwellers, on the other hand, were surviving on cheap meals of hot dogs and hamburgers at automats such as Horn & Hardart’s. Bread and soup lines snaked around the block.

Food producers weren’t about to let the scarcity of money take a bite out of profits. The National Biscuit Company created Ritz Crackers in 1933 and shortly afterward offered a recipe that would remain an adored oddity for over 40 years: Mock Apple Pie. Made almost entirely from Ritz Crackers, the ersatz pie stood in for the real thing, which, because of apple prices, was more expense to make.

In 1937, Hormel pitched in by developing arguably the most indestructible of all comestibles: Spam. Because its shelf life clocks in at more than seven years, few American kitchens (and later World War II military troops) were without it. Almost from Spam’s inception, cults — er — fan clubs were formed to honor and praise this mighty loaf.

A sign that the Depression was loosening its grip was witnessed in 1936 when Irma Rombauer, a housewife from St. Louis, published The Joy of Cooking (Bobbs-Merrill). Filled with practical information that was written in Rombauer’s accessible style, Joy regaled its readers with recipes for nearly everything, including longed-for meat. Though detractors criticized the book’s blanding of the American palate with its use of tasteless white sauces, reliance on vegetable shortening and insistence on overcooked vegetables, it sold out generation after generation to become one of the most beloved cookbooks of the century.

1940—1949

The nation had barely enough time to catch its breath from the hardships of the Great Depression before we were catapulted headlong into the horrors of World War II. Almost overnight a great migration of humanity was under way, with men marching off to Europe and the South Pacific, and women marching out of kitchens and into factories.

Many American homes lost their household help too. “Before the war there was a servant or two in many homes — now suddenly there wasn’t,” says Bronz. Standing patriotically side by side in factories across the country were hostesses and their former maids or cooks. “The war effectively democratized the nation,” she adds.

And in its democratization every family had to ration its food. The government restricted each American to 28 ounces of meat per week (overkill by today’s standard), plus limited the amounts of sugar, butter, milk, cheese, eggs and coffee permitted. As a result sales of convenience and prepared foods increased. “This is when margarine came in as a replacement for butter,” interjects Barnard.

“The government encouraged Americans to plant Victory Gardens,” says Ray. “The vegetables from these tiny plots of land, or sometimes larger cooperatives tended to by several families, helped to fill out compromised dinners.” Reflecting the times, women’s magazines of the day featured recipes for fresh vegetables, while the vegetable sections of popular cookbooks fattened.

“Americans didn’t mind the sacrifices,” says Kraig, “because it was a great patriotic effort.”

By 1948 the war was over and our thriftiness was rewarded by the beguiling Chiffon Cake. Originally dreamed up in the late ’20s by insurance salesman, Henry Baker, the cake grabbed the attention of diners at The Brown Derby restaurants, for whom he was now baking. As buzz spread of this delicious, airy cake, Baker was plied with requests and offers for his closely guarded recipe. It wasn’t until General Mills bought it in 1947 that the secret ingredient, vegetable oil, was revealed. In no time the cake made its way into nearly every kitchen as a sweet counterpoint to almost 20 years of deprivation and sorrow.

Recipe

1950-1959

The 1950s brought a renewed vivacity to the country. Hope soared, giddiness rippled and money flowed. As long as I Love Lucy was on the newly invented television, life was good. So good, in fact, that over 16 million babies were born during the first half of the decade.

Gastronomically, though, the Fabulous Fifties were anything but. Experts enthusiastically denigrate the decade as the nadir of American cuisine. The mass distribution of processed foods, thanks to transportation, is often blamed.

“The critical thing about food in the postwar years was the building of the national highway system,” Kraig points out. “Once that was built, [food] processors like Oscar Mayer became really big. And then there was the rise of McDonald’s and [other] hamburger chains along these highways.”

Bronz offers an additional explanation for the dearth of appetizing food in the ’50s: “Once Mom has been out of the house for the duration of the war, she found it really difficult to go back home and work as a housewife. It was at this time that we got all those ads about appliances and prepared foods freeing us from the kitchen.”

So we turned to the well-advertised can, package and pouch. Soups were available both in liquid and dry form, Tang landed on supermarket shelves and frozen dinners poised precariously on trays in front of TV sets nationwide.

Introduced in 1953 by Swanson, 98-cent TV dinners were the ultimate time- and energy-saver of the modern kitchen. A flick of the wrist turned back foil revealing turkey and stuffing floating in gelatinous gravy, whipped sweet potatoes and peas. About a half hour in the oven, and dinner was done. With nary a dish to wash.

Another favorite from the prepackaged ’50s was California Dip. Nothing more than a mixture of Lipton Recipe Secrets Onion Soup Mix and sour cream, the dip was the first thing to disappear at parties. According to Lipton brass, over 220,000 envelopes of mix are now used daily — most of which end up as dip, not soup.

Tuna noodle casserole, sloppy joes, frozen fish sticks, Grasshopper Pie and drinks filled with neon-colored umbrellas conspired to make the ’50s the epitome of culinary kitsch.

Yet even in this decade of gastronomic debasement a few dishes managed to shine. Beef Stroganoff, with its rich sour cream sauce, was considered the height of contemporary entertaining. Depending upon one’s budget, it could be made with strips of medium-rare sirloin or ground beef. With one dish you could impress the neighbors or feed the in-laws.

Something happened during the end of the decade that ushered in a new era of American cooking. “At the end of the ’50s, jet travel came in, and that meant Paris was suddenly seven hours away instead of 20,” says Anderson. “Veterans, who had tasted foreign food while in combat and were hungry for more, packed up their families and headed off to Europe and the Orient.”

While overseas, wives gathered kitchen equipment by the armful, determined to re-create many of the dishes she had tasted there. Unfortunately, with the exception of James Beard, there was little in the way of reliable instruction back home. That was until a charming, six-foot woman with a voice reminiscent of a throttled goose cowrote a tome called Mastering the Art of French Cooking (Alfred A. Knopf, 1961).

Recipe

California Dip

1960—1969

Julia Child was without a doubt the quintessential dish of the 1960s. She tottered into our lives like a marvelously eccentric aunt at the ideal moment: Jacqueline Kennedy had just installed a French chef in the White House kitchen, and our collective appetite was whetted.

Julia (everyone’s on a first-name basis with her) was keenly aware of her good fortune. In an interview with Leslie Brenner, author of American Appetite (Bard, 1999), Julia quipped that “I happened to come along just at the right time. If it had been a bit earlier, it wouldn’t have gone over…People were reading about what the Kennedys were eating. They just needed someone, and I happened to be the right person.”

She nearly single-handedly yanked us back from the crumbling edge of a culinary precipice and reintroduced us to the luxuries of French cooking (read: butter, eggs, cream and lots and lots of Cognac). Only this time is wasn’t just the rich who could afford such extravagance. The growing middle class had money and, like their wealthy predecessors of the ’20s, was more than ready to learn and indulge.

Yet what accounted for Julia’s uncanny success? Barnard’s assessment: “She was highly entertaining, very smart, and gave you the confidence to do really elaborate things. She was a great showman.”

“Julia’s totally nonthreatening,” adds Bronz. “I don’t understand why — she’s six feet tall and wields a knife, yet she makes you feel as if you can do anything.” Perhaps Ray sums it up best: “The newly affluent were trying to attain culture. She made French cooking very approachable. You acquired culture without feeling intimidated.”

From her TV show, “The French Chef,” came many classic dishes. Julia made good on Herbert Hoover’s promise of “a chicken in every pot” with her wildly popular recipe for Coq au Vin. A simple chicken dish made with mushrooms, onions, bacon and red wine, Coq au Vin was copied in millions of kitchens around the country. The dish was so well-loved that Julia included it in many of her subsequent cookbooks. But while she whipped up Boeuf Bourguignon, Mousse au Chocolat and Duck à l’Orange under the hot lights of the makeshift TV studio in Boston, another movement was afoot.

The late ’60s brought social unrest, growing tension over the Vietnam War and hippies with an unquenchable hunger for unprocessed, proletarian food made from scratch. Derogatorily referred to as granola-crunching, Birkenstock-wearing kind of folk, they eschewed anything prepackaged and began making their own products such as fresh bread, peanut butter, tahini and hummus.

Eventually even the most establishment-entrenched conservatives became curious. While it may have been a novelty to travel to the local cooperative to pick up fresh bean sprouts and gawk, it wasn’t long before some of the more adventurous traded in suits for tie-dyed T-shirts and opened restaurants. Regular items on the menu were vegetarian chili, guacamole, gazpacho, zucchini bread, lemon bars, carrot cake and, of course, granola.

The schism between Julia’s traditional French dishes and the appearance of “hippie food” in the course of only a few years proved jarring at the time. It was the first indication, however, of the speed with which food was evolving. The remaining three decades of the century would only build upon the ’60s and surprise us with greater diversity, occasional pomp and unbridled imagination.

Recipe

1970—1979

Tom Wolfe christened the 1970s the Me Decade, and understandably so with the boom in EST, wife swapping, recreational drug use and transcendental meditation–-TM for those in the know. In defense of those long-ago pleasure seekers, there were plenty of reasons for self-indulgence: most notably the Vietnam War, rampant inflation and Nixon.

We also indulged our tastes and developed a ravenous and eclectic appetite. We ricocheted from Buffalo Chicken Wings to Pasta Primavera to Walnut-Encrusted Goat Cheese Salads to homemade Crock-Pot chili in the course of a week. Brunch, replete with quiches of all sorts, became de rigueur. No self-respecting diner would be caught dead eating before 11:30 a.m. on a Sunday morning. By decade’s end, no self-respecting man would be caught dead eating quiche.

The Immigration Act of 1965 opened our doors to millions of Asians and was responsible for the exotic restaurants that were now springing up in even the most homogenized neighborhoods. The first to hit were Szechuan palaces, known for their hot and spicy cuisine. Foodies, whose taste buds until now were accustomed to nothing hotter than pepperoni, were happily chugging glassfuls of water in between searing bites.

Hungry for more, we soon feasted on Hunan, Vietnamese, Korean and, in the 1990s, Thai specialties. Many experts point to the ’70s as the beginning of America’s love affair with heat. It would take only 20 years before salsa surpassed ketchup as the most popular condiment.

The American palate had finally been unleashed, and anything ethnic was worthy of consideration. Italian food, primarily American adaptations of Sicilian and Neapolitan dishes, now turned to Venice, Abruzzi, Tuscany and Milan for inspiration.

“Many Italians from the North had money and came to this country in the ’60s and ’70s to open restaurants,” says Lidia Bastianich, host of PBS’s Lidia’s Italian Table and author of the companion cookbook of the same name (William Morrow, 1998). “What fueled the renaissance of Italian food in this country was the curiosity of Americans,” she adds. “They were willing to try anything.”

Bastianich recounted how during the ’70s she occasionally featured a dish from northern-Italy such as Vitello Alla Bolognese or Fettuccine Alfredo in her restaurant along with more familiar Italian-American dishes. By the end of the decade only a handful of the hybrid dishes remained.

Despite such ethnic fervor, one of the most popular dishes of the day was the very classic, very British Beef Wellington — a fillet of beef tenderloin coated with pâté de foie gras and a duxelles of mushrooms that are then all wrapped in a puff pastry crust. Some believe that Wellington’s popularity had more to do with America’s competitive spirit than with any deep passion for British cuisine.

It began in the ’60s when couples started dabbling in a bit of culinary one-upmanship. Dinner parties with friends became elaborate as complicated recipes appeared on tables with greater regularity. Beef Wellington was considered the height of difficulty and expense because of the preparation of the puff pastry and the price of the pâté de foie gras. Kudos and furtive jealous glances went to the cook who mastered such a bear of a recipe.

Although Beef Wellington went the way of Beef Stroganoff and Boeuf Bourguignon, it did stage a comeback in magazines such as Gourmet in the ’90s, when prepackaged puff pastry and domestic foie gras made it much easier and less expensive to make.

The ’70s gave rise to another icon who began her own revolution to rival Julia’s. From her famous Berkeley, California, restaurant, Chez Panisse, Alice Waters reintroduced the notion of cooking with natural, seasonal ingredients–-an almost forgotten concept because of the prepackaged-food boom. Her mantra: fresh food, simply prepared.

To remain faithful to her ideology, she scoured organic farms for fresh, interesting salad greens and vegetables. Through sheer will Waters marginalized iceberg lettuce to make way for arugula, mesclun and chicory. Her passion and respect for food attracted a coterie of young chefs who, under her tutelage, would bring her California Cuisine to the rest of the country — a refreshing counterpoint to the excess of the next decade.

Recipe

1980—1989

Think early 1980s and certain images come to mind: the Reagans draped in designer clothes, Trump’s gaudy towers, and, most horrific, oversize restaurant plates cradling an infinitesimally small amount of food. Nouvelle Cuisine, as it was coined in the late ’70s in France, was the hottest thing here. Diners now paid astronomically more to eat significantly less, and loved it. It was a sign of status to wait a half hour for a table, eat a pigeon’s portion of food, and then be the first to foist a platinum credit card on the waiter, loudly declaiming to the table, “This one’s on me!” The stock market was everyone’s best friend, and generosity flowed. But soon diners rebelled and instead opted for plates filled with sumptuous delights.

At home we collected all types of gourmet foods and gadgets. Cabinets overflowed with $65 bottles of virgin olive oil and 50-year-old balsamic vinegars. Countertops were cleared to make way for the new stand mixer and the food processor. And drawers fairly bulged with the newest culinary gizmos, the result of reverent pilgrimages to the Mecca of cooking, Williams-Sonoma.

This was also the time when many chefs stepped out from behind their stoves and found celebrity. Wolfgang Puck became a household name as his much-touted gourmet pizzas attracted the new Hollywood glitterati to his restaurant, Spago.

Paul Prudhomme, a sizable man with an equally sizable talent, started the Cajun trend at his New Orleans restaurant, K-Paul’s Louisiana Kitchen, with Cajun Popcorn and his now famous blackened redfish. It took no time for others to follow, blackening everything from chicken to, yes, spaghetti. A worthwhile trend, it unfortunately was taken to ridiculous extremes and petered out by decade’s end. It took the flamboyant Emeril Lagasse on cable’s Food Network to revive it in the 1990s.

Although French food had fallen out of favor, Jean-Georges Vongerichten began serving such delicacies as L’Oeuf au Caviar — a shirred egg served in its shell, topped with caviar and crème fraîche — at Restaurant Lafayette in New York City (where the author was one of two front waiters). Even the most jaded foodie was seduced back.

The late ’80s saw Charlie Trotter open his self-named restaurant in Chicago. Leading the charge away from culinary excess, Trotter turned instead to infused oils, vinaigrettes and light meat and fish reductions. The combination still makes critics gush. Later Vongerichten orchestrated a similar shift with his famous vegetable and fruit essences.

Besides celebrity chefs, it seems as if nearly every style of food had its 15 minutes of fame. Ethiopian cuisine, Tex-Mex, southwestern cooking and Spanish tapas tempted us. The only true winner: Tex-Mex. The others enjoyed flashes of fame (mostly in larger cities) but eventually faded from menus.

On the dessert front, chocoholics swooned when faced with decadent flourless chocolate cakes, truffles and chocolate crème brûlée. Desserts also grew skyward as pastry chefs, taking cues from architecture, built towers of sweetness that rose from the plate. Diners often wondered whether to use a fork or a sledgehammer to eat.

History repeated itself when, on October 19, 1987, the stock market once again plummeted — this time 508 points. As with the crash of 1929, spending skidded to a halt and we ran for cover. Haute restaurants began emptying out as more down-home eateries began filling up. Simple comfort food such as chicken-fried steak, mashed potatoes, meat loaf (again), pot pies, pasta, and chili became the rage. “Anything that was reminiscent of childhood was welcomed,” comments Bronz.

A beloved dish at the end of the decade was Risotto Milanese. It was so popular that diners ordered the creamy, saffron-infused rice dish without even opening their menus. “I think risotto’s popularity has to do with the fact that it’s the kind of food that embraces you and holds you tight,” coos Bastianich. “It comforts the soul.”

One problem: All that comforting added up to a lot of extra pounds that had to come off.

Recipe

1990—1999

In the early ’90s, under the supervision of personal trainers who looked like the Michelin Man, we ran nowhere on treadmills, bicycled hundreds of thousands of miles while watching TV and climbed enough steps to reach the moon.

At the same time, manufacturers found ways to make everything reduced fat, low-fat or fat-free — even fat. What foodie can forget where he was when he heard that Olestra, the new nonfat fat, was on its way to market? But try as we might, most of us didn’t lose weight. We fooled ourselves into believing that because we were eating low-fat foods we could guiltlessly binge.

Instead of exercising ourselves senseless at the gym, the more moderate among us loosened our belts a notch and began partaking of naturally healthy cuisines, most notably Pacific Rim and Mediterranean. Diners delighted over such fruits de mer as Poached Monkfish With Fennel, Salmon Tartare and Grilled Sea Bass. Sushi and sashimi remained favorites — not as a show of status, as they were in the ’80s, but instead as a matter of taste.

Northern Italy also continued to hold sway over American palates, yet unlike in earlier decades, its food became more distinctly regional. Countless variations of polenta, focaccia, and tiramisu captured our imagination. In fact, it was possible to eat nothing but bruschetta and never exhaust the subtle regional differences.

Inspired by the availability of these foreign foods, chefs began combining cuisines in a trend known as fusion cooking. Coconut broth and tortellini were paired with basil and steamed littleneck clams, and the results were dazzling. In an attempt to highlight these unions, anything distracting was removed so all that was left were unadulterated flavors. It was a return to simplicity, promoted by Waters two decades earlier. “We began finding our way in the ’70s, got outrageous in the ’80s and when we became confident [in the ’90s], we went back to simplicity,” summarizes Barnard.

Pure flavors ruled, and the more intense, the better. Take Vongerichten’s Warm, Soft Chocolate Cake. This ambrosial minicake is absolute chocolate in two forms: a warm, molten center surrounded by a tender, protective shell. Despite its intensity, however, it has nothing of the heaviness of Mississippi Mud Pie or the ubiquitous flourless chocolate cake. Perhaps that’s why it’s one of the most copied desserts in American restaurants.

The movement toward simplicity and paring down also found its way into the home. Powered by the domestic juggernaut Martha Stewart, “cocooning”–-the turning homeward to nest with family and friends — began. We couldn’t get enough of good things like canning, cherry pie and handmade wrapping paper.

As priorities shifted, we began carving out more time for herb gardening, PTA meetings and — arguably one of the most revolutionary cooking tools ever — the Internet.

With the World Wide Web we now had instant access to millions of recipes from around the globe. Want to make Filet Mignon With Mustard Port Sauce and Red Onion Confit? (Our tastes had once again turned toward the luxurious, owing to a booming end-of-the-century economy.) Double-click Epicurious.com and dinner’s nearly ready. Confused about which cookbook to buy? Consult Amazon.com. There you’ll find plenty of reviews from the newest breed of critics–-savvy consumers. If it’s encouragement you need, stop by one of the thousands of online newsgroups for a chat.

Waiting out these last days of the waning century, one naturally becomes reflective — that is, if you were old enough to be born, as Brenner puts it, B.C. — “Before Child.” So much has happened since Julia began flickering on TV screens in 1963; so much more since the turn of the century. But mixed with nostalgia is curiosity about the future. What’s next? What will a person sitting in your kitchen 100 years from now, reading the news electronically for sure, be eating?

Hmmm.

Recipe

(Pardon my English, I speak French)

Thank you for this article which was really interesting ! I can say now I learned a lot about American Food and its history. I wonder you have actually no time to do an update of this article but I hope even so you’ll do this one day. Why ? Simply because I realized with your piece we (Europeans or in any case among my friends) don’t know much about American cuisine or American tastes. Finally I suppose we have more in common that we think (love of good food for example) … ?

Anyway, thank you again for this great article.I think I’ll read soon your other articles 🙂

Aryona, s’il vous plaît pardonnez mon français. Je ne écris pas bien–et j’utilise Google Translate pour écrire cela. Merci pour vos aimables paroles. Je suis très heureux que vous avez trouvé l’article utile. J’ai réfléchi à la mise à jour, mais la recherche qu’il nous obligera énorme. Jusque-là, je vous souhaite beaucoup d’heures heureuses de la lecture de nos articles.

I was wondering if someone could point me in the right direction. I have in my possession a never-been-opened WWII bread slicer, still wrapped with excess of grease, and in crate—I figured that a museum or collector might be interested.

More details offered,

Sincerely,

Jessica

There are a few possibilities, Jessica (I’m assuming you’re only interested in museums in the US — ‘though there’s a great bread museum in Germany):

Michigan State University

East Lansing MI

Reitz Collection of Food Technology

Department of Anthropology/Calif. Academy of Sciences

875 Howard Street (between 4th and 5th Streets)

San Francisco CA 94103-3009

Not exactly on topic, but might be interested:

The Toaster Museum Foundation

1003 Carlton Ave., Ste. B

Charlottesville VA 22902

This marvelous gem, almost as brilliant today as when new, needs to be updated.

When can we expect you to add the last decade? Perhaps you should update this piece with more recipes and offer something like a CD with all of the recipes bundled with the article.

Thank you. Adding to this piece is a very, very good idea, but I think I’ll wait until the first decade of the 21st century is over so that it could be comprehensive. (That’s not too long from now!) And adding more recipes is a wonderful idea. And a CD? Are you LC’s unofficial sales manager?

Rather than your sales manager, I am more of a greatly appreciative reader with as much of an appetite for satisfying writing as for, well, the rest of what makes this site valuable.

Your article surveys the 100-year term with brisk writing that touches on unarguably salient points. It should benefit from an update in two senses: certainly the decade that will end with this year (as in counting 2000 as the first year of the decade and this year as the last) is ripe for a comparable summary, which will update this 100-year essay; the next update would be to extend your article to book length, with lots more recipes and photos and…(but, alas, you know the challenge of writing and putting together a good cookbook), and coverage of more of the less salient points.

Let’s see. M. F. K. Leite? Only after you give us recipes for how to cook a wolf (the ones which happens to be at the doors of many would be wonderful). Perhaps Elizabeth David Leite? Nawh. There is no fat lady to write an intro.

When James Dickey (he of ‘Deliverance’ and much good poetry) spoke with Bill Moyers about culture, Mr. Dickey honed in on cuisine as integral to culture. He claimed that the only indigenous cuisine is Southern, all else being imported. “Dining through the Decades” seems to collect evidence that suggests Mr. Dickey’s judgment might have been a bit clouded. It would be wonderful to read an expanded version of “Dining” and what I suspect is many and sundry examples of a cosmopolitan cuisine…with recipes.

Sales manager? Nawh. More of a long silent consumer of your work who is now yelling into the kitchen for more.

F.M., Your reply had me laughing so hard I scared both cats. Thank you for your vote of confidence, but I don’t think I could write a book like this. It’s not my forté. The article, written so long ago, nearly had prone on the floor and panting with anxiety. But thanks for the comments. (Of course, if you could persuade my publisher to give me a six-figure advance for the book, I’d reconsider.)

Well?

Isn’t it about time to take aim on the 20,000 buyers of your collection of Portuguese recipes and feed us another book? Or at least the update to this essay (which you seem to have promised to undertake) might be a tidbit…

Let’s see. … I recall, with the help of your website, you saying

“Adding to this piece is a very, very good idea, but I think I’ll wait until the first decade of the 21st century is over so that it could be comprehensive. (That’s not too long from now!) And adding more recipes is a wonderful idea. And a CD?”

It is not news that the first decade of the 21st Century is long over. Isn’t it about time to expand the piece into a book length review for a few 20,000 or so of only your closest friends? Obviously, it IS your forte….

F.M., If only a book publisher would buy the idea. But it’s more complicated than just choosing to do a book. So much more goes on behind the scenes regarding what kind of book is bought, the topic, its appeal, its popularity, etc. As you can see, there are only seven comments on this post–five are ours. That says something.

The next book I’m working on is a Leite’s Culinaria cookbook. Food history is the forte of someone like Gary Allen.

Hey David, just found this great overview of American cooking and would like to point out that we’re well into the second decade of the 21st century … sure you don’t want to do an update? Locovores, GMOs, organic stuff … lots to cover. I can hardly wait!

Judy, well, thank you for the vote of confidence, but I’m still recovering from writing the first article!! Not sure they’ll be another coming any time soon. At least from me. You game to write it?!