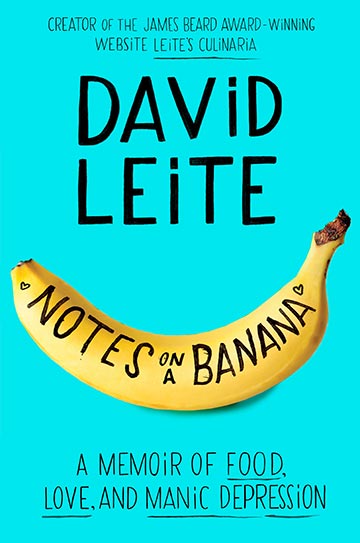

Today, Notes on a Banana: A Memoir of Food, Love, and Manic Depression publishes. It’s taken nearly a quarter of a century for me to write this book. I first sat down to share my story with the world on the very first laptop Apple ever made. That was in 1992. I didn’t get beyond several paragraphs, which are in the book, because, frankly, I didn’t have the writing skills yet. Also, I was still living my story. I didn’t have the distance I needed. The following year, I met The One—Alan Dunkelberger—and, as many of you know, my life was forever changed. I was young, thin, and beautiful when we fell in love. Emphasis on thin. I had recently lost more than 70 pounds, and no one—no one—was going to make me gain it back. Ha! Was I wrong. In this excerpt, I share some of the differences between Alan and me when it comes to food. And how I learned something in those early and carefree months of our relationship. I learned to linger over a meal, something my family didn’t do. We, proudly, were eaters. Alan coaxed me into becoming a devotee of everything about sitting down to eat.—David Leite

Alan, I soon discovered, was a diner. He loved everything about the ceremony of the table. Whenever we were at his apartment on West Eighty-Fifth Street, he’d lay out placemats, those gold-rimmed plates from Macy’s, silverware, glasses. He slipped rolled napkins into shiny rings, like wedding bands, and lit candles and played music—Kenny G, of whom, for some reason, he was inordinately and unfortunately fond.

He especially enjoyed lingering after a meal. He’d push away from his plate, cross his legs, and fold his hands in his lap, like he was ready to be told a story. We were to talk, I came to understand. About our day, about a book one of us had read, about the news. Anything, really. Company and conversation were what was important. I figured it was something he’d picked up from his family. Not so, he told me. When he was a kid in Baltimore, dinner had been a hit-and-run. At suppertime, his stepfather rarely spoke to him. Instead he would glower across his plate at Alan’s mother. Alan would sit in his chair, head down and silent, waiting for the first chance to slip away unnoticed.

I didn’t get this concept of lingering. My people are not lingerers. We’d sit down, platters passing in both directions, a raucousness rising from the table, even when it was just my parents and me. Ten minutes after finishing, regardless of how many of us there were, there was no evidence we’d ever shared a meal. Tables were stripped, dishes washed, food covered and put away. The women then gathered in the kitchen, getting ready for the next meal; the men sat outside on lawn chairs, waiting for the next meal; the kids played in the street, building up an appetite for the next meal. We were eaters, not diners.

Weirdly, food factored in little in Alan’s dining ritual. It wasn’t so much what he ate but how it was presented that mattered. “You can serve shit on a shingle, but as long as that shingle is bone china, no one’ll notice,” he liked to say. As if to prove his point, we were walking up Broadway past Burger King on One-Dollar Whopper Night. Not one to pass up junk food, especially if it was a bargain, he peeled off into the restaurant. At home, he pulled two burgers from the sack and set them on a plate. He arranged fries around the rim and sat down to wait for me. I foraged in the kitchen cabinet for the box of Fiber One cereal I’d stashed there, and grabbed a matching china bowl, a spoon, and a quart of skim milk. “Yes, yes,” he said, motioning for me to eat, his falsetto quavering in his best Julia Child impression. “Bon appétit!” From the satisfied smile splitting his face into two, you would have thought he was eating at Buckingham Palace. Afterward, even though the couch, Roseanne, and my laptop were calling, I lingered. For him.

But I was screwed. Losing and keeping off all that weight for those five years had required Herculean discipline. Not lingering at the table was one of the ways I prevented myself from swallowing donuts and spiral hams whole. So was pattern eating. Every morning on my way to the ad agency, I grabbed a bagel and orange juice. Lunch was a tuna-salad sandwich and a Diet Coke at my desk. Dinner consisted of either a bowl of cereal or, occasionally, pasta with low-calorie sauce. That was it, for a long time.

Alan didn’t understand why anyone who wasn’t overweight would want to limit consumption. All of his life he had tried to gain weight: gulping shakes and wolfing down high-fat foods, candy, and carbohydrates. Yet there we were: he on one side of the table, stuffing his face with burgers; I on the other, making do with three-quarters of a cup of sticks and twigs.

He undid me, meal by meal. Not because he was a great cook; he wasn’t. His mac and cheese came in a blue box. He had an unapologetic love for Velveeta and cakes with fruit cocktail baked inside. It was his act of cooking for me, along with his steadfast desire to make me happy, that released something inside—what I imagined the slow, seductive unlacing of a corset must feel like, and I could breathe again.

David, I’ve always appreciated presentation, but if I bring home a fast food burger and fries I can happily eat them out of their wrappers. Not my husband – like Alan, he’ll unwrap them and arrange them on his plate!

You and I are cut from the same paper napkin, Jean!