Singapore knows food. Across the small island, food stalls collectively flaunt what are perhaps some of the most extensive and diverse menus amassed in a single place on the planet. These emporiums of street food are where Chinese, Malaysian, Indian, and Indonesian flavors co-exist. Hainanese chicken rice could be considered the official dish of the open-air food markets, although there’s considerable competition from nasi lemak, laksa noodles, dumplings, and chili crab, making the entire Southeast Asian city-state a food lover’s nirvana.

Food hawkers recognized as national treasures

Singapore considers their hawkers so tied to their cultural heritage that the country led a successful campaign to have the practice added to the 2020 Unesco Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity. Some of the most craveable food on the planet is being promoted and preserved as an integral part of our collective culture.

Meaning? Unesco, or The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization, “seeks to build peace through international cooperation in Education, the Sciences and Culture.” Unesco looks to protect cultural heritage and the equal dignity of all cultures. Founded right after World War II, the organization is concerned with reaffirming “the humanist missions” of culture, and Singapore’s hawker stalls are considered an integral part of the culture, something that makes them unique and reflects the incredible food diversity found there—and only there.

The city-state recognizes not only that the food itself is a national treasure, but more importantly, that “these centres serve as ‘community dining rooms’ where people from diverse backgrounds gather and share the experience of dining over breakfast, lunch and dinner,” stated UNESCO on their website.

Some of these stalls have been in business since the early 1960s, often specializing in one dish and one dish only. After decades of cooking and perfecting their offerings, dozens of these food hawkers have been awarded Michelin stars for plates of food that cost only a few dollars. Many have also been made famous by celebrity chefs wandering the world, including the late Anthony Bourdain, with the offerings ranging from fried radish cakes and satay to Chinese duck and chocolate fudge cakes.

A brief history of Singapore street food

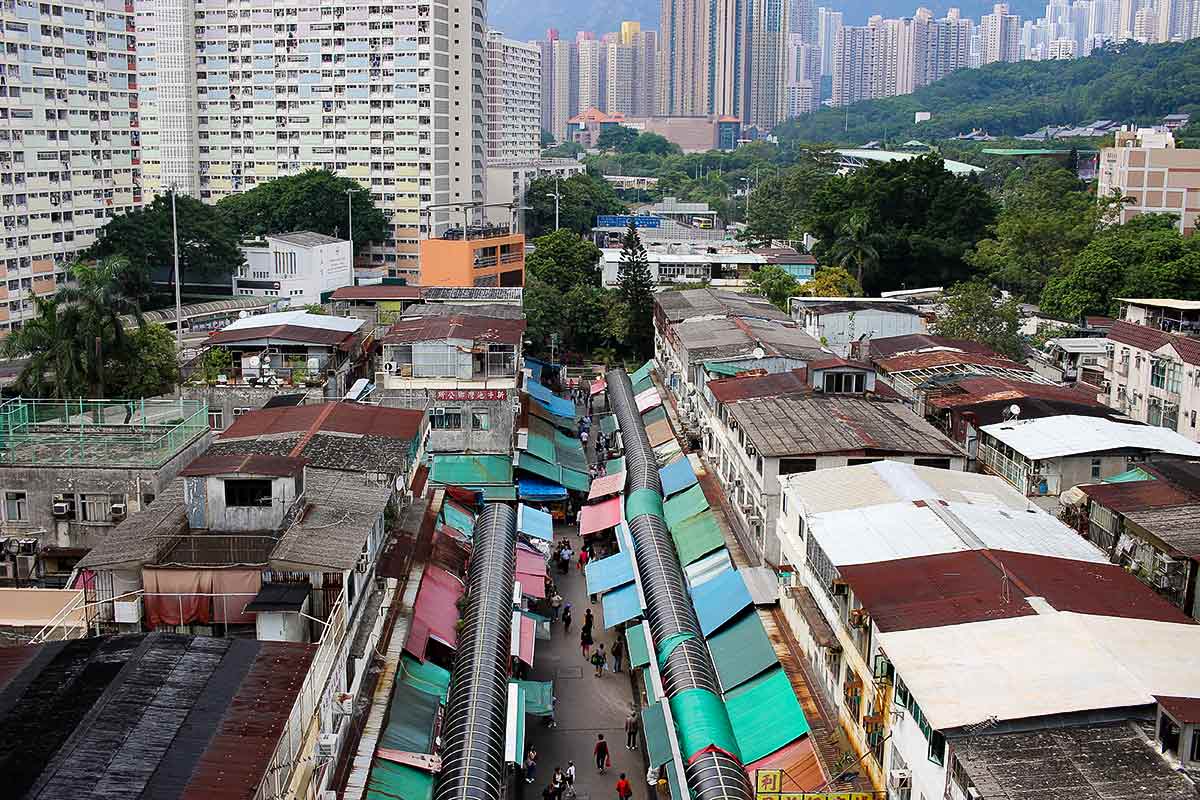

Street food has been available here for centuries, but it wasn’t until the late 1960s that the stalls were brought together in large, clean communal marketplaces, a tangible representation of the evolution of street food culture. Hawker centres (there were 114 at last count) are markers of the multicultural city-state that includes Chinese, Malay, Indian, Tamil and other ethnic designations.

Want to Save This?

The cultural diversity didn’t just happen by accident. Singapore’s government endeavored to accommodate as many ethnic cuisines as possible, to specifically promote inclusivity on the island. Singapore is a relatively young republic, having become an independent nation in 1963, but has still managed to successfully amalgamate a number of cultures in a small space.

With a population of 5.8 million in less than 284 square miles (730 square kms), which is roughly 3/5 the size of Los Angeles, hawker centres serve as meeting places. Racial and religious diversity brought to Singapore through an immigrant-rich society have combined to build a unique and international food culture.

On the endangered list

Now for the bad news. Part of the reason that these food hawker centres have been designated as culturally important places is that they are in danger of dying out. The last two decades have seen a rapidly changing society—one focused on technology and not on chicken rice. The median age of Singapore’s hawkers is 60 years old, and there aren’t many millennials lining up to take over the cramped and sweaty stalls or apprentice in one. As much as locals adore the food in hawker centres, few are interested in running a stall themselves.

It’s not so much an issue of long hours on your feet, as busy stalls only need to be open six or eight hours a day. The biggest problem is that “many Singaporeans still regard hawkers as a low-level trade,” says Leslie Tay, author of The End of Char Kway Teow and Other Hawker Mysteries. “The challenge is how to get more young people to go into the profession.”

“Hawker centers are likely the first places where people will try another [ethnic group’s] food,” says architectural and urban historian Chee Kien Lai, author of Early Hawkers in Singapore. “They’re open to everyone. You can get halal food or try Indian cuisine and get connected to different cultures and religions.”

Hopefully, these centres will continue to enlighten and expand our awareness for an unforeseeable amount of time.

*when I read the article’s title*

Let’s be serious – if you consider yourself a food traveller, that list is incomplete without having Singapore on it. Despite how expensive it is to live in that city, the government has regulated the system to make dining affordable. Dining there is awesome and an experience, more power to going for street food than high life. The high life is boring.

If you really want to get into the heart of the hawker’s centre, this is how you do it. Go with a group of people, and designate one person to one stall. They buy a selection from each – and ever forget one folk for the drinks stall; iced coffee has never been as good anywhere else. Find a table, have a spread and share around.

#^*@! Why did I have to remind myself of that? Now I am itching to get on a plane just for some chicken rice.

Haha! Thanks for the comment and the perfect clip, Mikey. I really enjoyed writing this article—I have a deep fondness for global cultures and foods. I haven’t yet been to Singapore but now I’m determined to go, one day. I’ve heard so many raving reviews about the coffee, too. Thanks for laying out the perfect trip for me!