For me, Julia Child will always be a mix of joy, delight, sadness, and anxiety. When I was a preteen, my brain felt unplugged from my mind, my body crowded with a blackness I couldn’t describe. All my attempts to explain the desperation I felt went un-understood. My parents tried, but after months and at a loss, my dad said, “Son, everyone has to cope. You’re just going to have to cope.”

“Cope.” To this day, I hate that word.

It took two more years of “coping” before I threatened suicide unless I could see a therapist. Of course, my parents found me an excellent doctor. But he never uncovered the cause of my distress. It took another 20 or so years before I got the diagnosis of bipolar II disorder.

This essay, written in 2014, was one of my first attempts to put into words what I’d felt so very long ago. And it was the response to this story, in the comments as well as via mail, electronic and snail, that led me to think perhaps I had something to say–not unlike what Julia felt when she heard of the 23 letters for viewers. Three years later my book “Notes on a Banana: A Memoir of Food, Love, and Manic Depression” was published. This essay appears in it almost word for word.

Like so many people, I love Julia for what she taught us in the kitchen. And while watching “Julia,” I laugh along with The One at her plucky perseverance and trumped-up antics. But I also say a silent prayer of thanks to her, through the wonderful Sarah Lancashire, for what she did for the sad, lost boy I was.–David

My backpack of school books slumped, unopened, against my father’s La-Z-Boy. My Top-Siders sat pigeon-toed near the breezeway door, where I’d mindlessly stepped out of them. I curled up on the floor in front of the TV, my head tucked into the crook of my elbow so my mother couldn’t study my face for signs that it was happening.

Outside, through the open windows, I could hear the neighborhood kids playing. The Jenningses. The Freeborns. The Medeiroses. Please don’t make me go outside, I begged my mother in my head. I just can’t do it. Outside always unsettled me. The bright sky, the backyard with a lawn like a crocheted green quilt, the street full of neighborhood kids. A 12-year-old’s rightful place terrified me, because it gave me no pleasure and reminded me just how troubled I was.

I cranked the dial on the old Motorola black-and-white TV, looking for channel 2, WGBH.

“You’re going to twist that thing right off,” my mother said. “Then what?”

“Sorry,” I mumbled into my elbow.

Just then the jaunty music from The French Chef mingled with the rhythmic thonk and hiss of my mother’s iron as she pressed my father’s underwear. Suddenly the hamster wheel of punitive thoughts in my head slowed. As I watched the show, mist from Mom’s spray bottle would every so often arc over the board, and I turned my face to its coolness. I felt happy—or, more accurately, I felt the absence of misery. Julia Child had that effect on me. So did sleep. Both of them temporarily stopped it all. The horrible sense of watching the world from the wrong end of a telescope, everything distanced and muffled. The bowling balls of anxiety that ricocheted through my chest with such force, they sometimes catapulted me out of movie theaters, church, family dinners. The pacing and hand-wringing. The relentless analyzing and trying to understand what was wrong with me. While the rest of my day was spent waiting to go to bed, Julia offered a 30-minute reprieve.

It took my soldiering through 23 more years of this hell and working with four therapists before I diagnosed myself with bipolar disorder—and another full year before the medical community agreed with me. “Bipolar II disorder, most likely with childhood onset” is what they decided. Perversely, I was relieved, happy even. Finally, I could put a name to all of this. “Guess what? I have bipolar disorder! I’m mentally ill!” I told The One. But I was also pissed off. It was fine to tell that to a 35-year-old adult with the cognitive ability and emotional support to take such an air-sucking punch to the gut.

But what about that poor scared kid stranded in the ’70s?

There were drugs back then, of course. At a loss after several frantic visits from me, our dolt of a family physician finally leaned against the metal cabinet in his office and shook his head in exasperation. “I can prescribe Valium if you want.”

“I’m only 12 years old,” I said in disbelief. He shrugged as if to say, So? I had no idea what was going on with me, but somehow I knew pumping me full of pills straight out of Valley of the Dolls wasn’t the answer.

I jumped off the exam table. “Come on, Dad,” I said to my father, who looked anguished that no one could find relief for me. For the first time in my life, I wished I were dead.

There were also sleepovers. Too often, though, the mental distraction I’d hoped for ended in burning humiliation, my friends and their families huddled together in their pajamas, looking on in the middle of the night while I called my father and explained how some exotic stomach virus had suddenly hit. (I’d learned that flus and viruses were the ultimate excuses because, unlike faked fevers, there was no way of checking their validity. Plus, they had the added advantage of making everyone all too happy to get me the hell out of their house.)

And there was reading. But it was rare that I could wring meaning from the words. Instead, I’d stare absently through the book, pretending to read so that my parents wouldn’t worry. Sometimes my mother, lying next to me on the couch, would toe me in the leg when I forgot to turn pages.

Luckily, though, there was Julia. Show after show, she fumbled with pots, wielded a sword over her famous kick line of fowl, and thwacked pieces of meat the way mothers back then would swat the asses of bratty kids when they misbehaved. This soothed me. She accomplished something very few people could back then: She helped me forget myself.

It was Julia’s unchecked joy—something I begged God for every night—that captivated me. My rapid cycling—those capricious and exhausting mood swings I experienced countless times each day—lifted for that half hour. I felt normal. Or what I imagined was normal. Sometimes I’d even feel enough like myself to do a rousing imitation of Julia for my mother. As I tootled, my voice rising and plunging, she’d fall back against the door and laugh. Her fingers, red from housework, would burrow under her cat-eye glasses to wipe away tears—as much from relief as delight, I now suspect.

Oddly, I don’t recall a single dish Julia made on the show. What I do remember is the floppy “École des 3 Gourmandes” patch pinned to her blouse. I remember my dog Rusty, who could always sense pain, lying against my back. And I remember that voice—that marvelous voice, a sound so swooping, so throttled, I always thought it’d make the definitive voice for an animated Mother Goose.

At 53, I’ve accepted that my bipolar disorder is as stable as it’ll ever be—which, compared to the emotions of my preteens through my late 30s, is rock-steady. I have pills to thank for that. Proper pills from a proper psychopharmacologist. Three times a day I flood my system with chemicals that I can feel stroking my nerve endings. Sometimes they pull me up, sad and broken, like a rusted car from the bottom of a dirty river. Other times they whisper in my ear and pat my hand until the irritability, machine-gun-fast speech, and grandiose thinking melt away.

Over time, I’ve added my own weapons to my bipolar arsenal. Things no shrink can prescribe and no therapist can analyze—namely, cooking and writing about food. Even on my worst days, when it feels like I have some gargantuan creature threatening to drag me down through the couch cushions, the simple act of swirling a knob of butter in a hot skillet can cheer me. And nothing mercifully bitch-slaps depression for a few hours like the utterly frustrating and highly improbable act of stringing together words, like pearls on a necklace, and turning those words into stories.

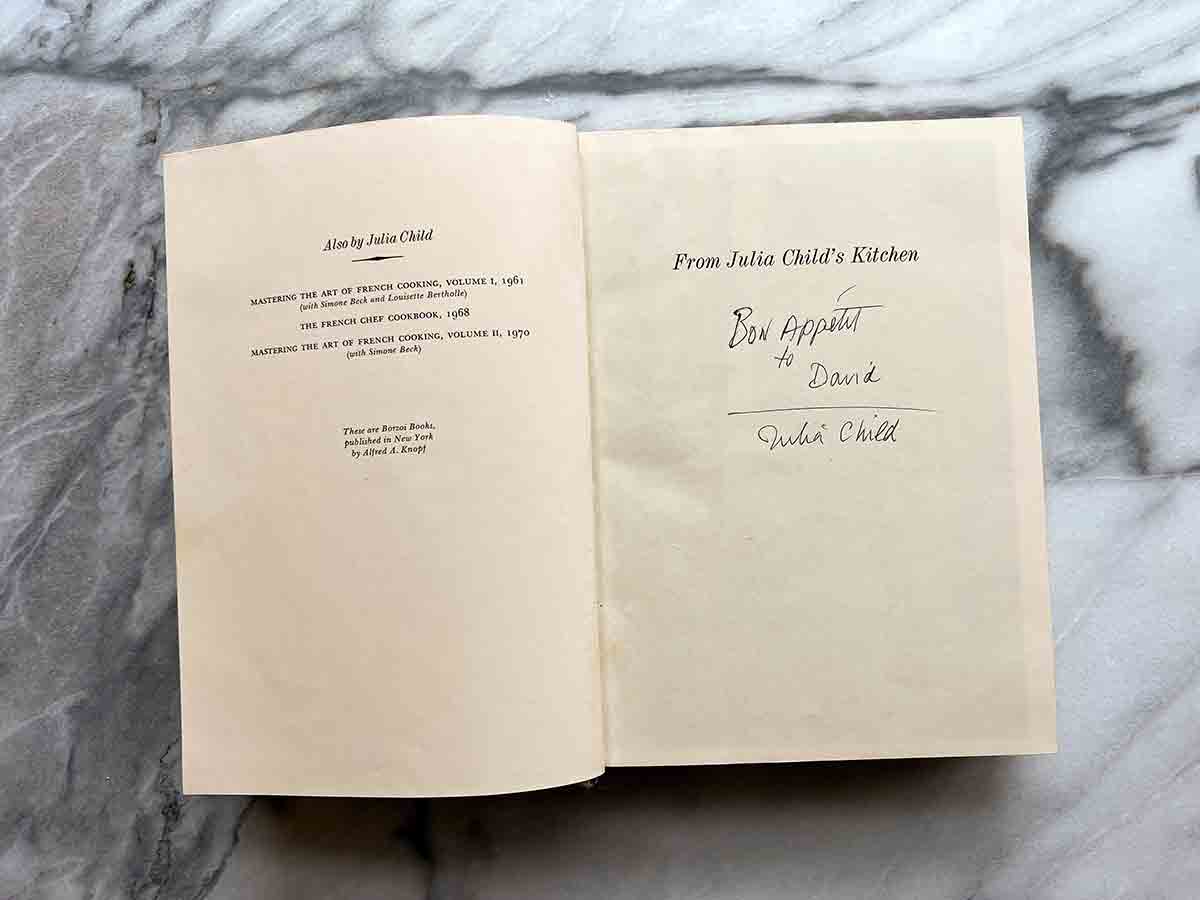

Not long ago, I was clearing out shelves of cookbooks to give away to the local library. As I sat on the floor flipping through each one for lost shopping lists and other scribbles, I opened a beat-up copy of From Julia Child’s Kitchen. Scrawled on the title page in an unsure hand was “Bon appétit to David—Julia Child.” A former therapist of mine who was friendly with Julia had asked her for this favor. When she signed it all those years ago, I’d forgotten my afternoon reprieves in front of the TV. Back then I still had no idea what the thing was that once had such a grip on me; I just assumed I had outgrown it. But within months, it blindsided me again with such brutality I had to move out of my and The One’s apartment and into a friend’s house because, as with my father two decades earlier, I couldn’t bear to see what my newly labeled illness was doing to him. Every night for almost four weeks, I crawled into my friend’s childhood bunk bed right after work and read the book over and over again while the summer sun streamed through the curtains. It was as if Julia’s writing tapped my brain like a keg and drained the blackness for a while.

“What are you going to do with it?” The One asked, toeing the book in my lap with his slipper. I ran my hand over Julia’s inscription. Though it’s a totem of all that pain, I couldn’t give it away.

“Saving it,” I said. “You could say it kind of saved me.” He smiled and walked into the kitchen to start dinner.

It’s tempting to think that watching Julia all those years ago is somehow, consciously or unconsciously, the reason for my career choice. But it isn’t so. Before I turned to food writing, I was a failed graphic designer, day-care worker, actor (read: waiter), receptionist, past-life regressionist (another story for another time), and copywriter. Besides, in my late 20s and early 30s, food actually became the enemy as I lost interest in eating and dropped to an alarming 169 pounds, slurping nothing more than a bowl or two of Fiber One cereal at dinner each day.

But what Julia did do, which I’ll always be grateful for, was teach me, there on that nubby brown carpet in front of the TV and, two decades later, alone in that twin bed, that despite being bipolar happiness is possible. Even for me.

Oh my, cried as I read this – so open and beautiful. “the simple act of swirling a knob of butter in a hot skillet can cheer me” I understand, deeply and truly. Wishing you and The One many years of ups, (and some downs, let’s be realistic), and lots of swirled butter. Bravo!

Thank you, Mary. It touches me that the piece touched you. Cooking does have such a restorative effect. Wishing you and yours many years of happiness, too.

David your story took much strength to share…you are so loved and supported. I appreciate everything you’ve shared…. Both personal and recipes.

Cindy, thank you so much for your kind words!

david you’re tops in my book…love your recipes and you as well…thanks for all your wonderful recipes posts… pat

pat, thank you so much for your very kind words!