[I call Wolfert, but she hangs up on me. I call again.]

Paula Wolfert: I’m so sorry. I have a new telephone, and I was on the line with someone. I just don’t know how to use it [laughs].

David Leite: What’s the matter? You don’t know how to flash me?

PW: I did flash you. You didn’t flash back!

DL: [laughs] How are you?

PW: I’m very well, thank you.

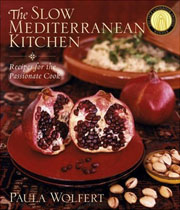

DL: I understand that things are [still] going great with The Slow Mediterranean Kitchen.

PW: They are. But you want to know a funny thing? When I first saw the cover, my first instinct was to cry.

DL: Why?

PW: I thought it looked like a dining room in a whorehouse. But now I love it. It’s so beautiful. I’ve never had so many pictures in a book. In fact, except for the first edition of Couscous and Other Good Food from Morocco, I’ve never had color pictures at all.

DL: I’ve been going through a pile of articles — written by you, about you, for you, because of you.

PW: Well, some of the really nice ones are up on my Web site, paulawolfert.com. My favorite is the one in which Nicholas Lemann calls me a diva. It’s on Slate.com. He refers to me as the food world’s equivalent to John Cage or William Gaddis, and that I’m doomed to be poor because no one ever gets it about someone like me. He was obviously madly in love with me [laughs]. I’m just kidding, but he really said I’m the one person who traipses up to the top of some mountain and gets that one recipe that everyone wants out of that one woman — using only sign language. It’s wonderful and all, but it’s not true, it’s not true at all. But it’s very funny. But he calls me something…

DL: [quoting the article] “Paula Wolfert is very high maintenance, but she’s worth it.”

PW: Exactly!

DL: It reminds me the first time I met you. You walked into the room, and everyone just burbled with excitement. I had no idea what you looked like then. Suddenly everyone was kissing you and hugging you. I turned to a friend and asked, “Did Jesus just walk in the room?” Do you always have that effect on people?

PW: No, not at all. I started publishing at the same time as Giulliano Bugialli, Marcella Hazan, and Madhur Jaffrey, but I just took a different path.

DL: And it’s a path people obviously like. What path was that?

PW: I’ve just done everything my way. I’m very passionate and single-minded about what I’m working on. For example, I got to a point where I actually stopped all other work on The Slow Mediterranean Kitchen to work only on the cannelés recipe for three months. I didn’t do anything else. I flew to Bordeaux to get permission to use the recipe. It’s the true recipe. I was given the real recipe 20 years ago, but I didn’t know what it was because when I was living in Bordeaux, I never heard of canelés de Bordeaux.

DL: Me either, until I read your book.

PW: It’s one of those recipes that goes in and out of fashion. In the ’80s it was well out of fashion, but the pâtissier Daniel Antoine gave the recipe to Madame Daguin, the mother of Ariane [of D’Artagnan fame], to give to me because he knew I was working on The Cooking of South-West France. He thought it should be in there. Then five years later, these desserts take off again. The pâtissiers of Bordeaux got together, all 87 of them, and made a pact. They staged a linguistic coup d’etat and removed one the n’s from the spelling — cannelés — to distinguish theirs from imposters. Then they wrote down the recipe, put it in the vault, and wouldn’t give it to anybody. The funny thing is they were fine with my having it as long as I didn’t publish it in French. I mean, it was ridiculous. I pretty much perfected the recipe using Swan’s Down Cake Flour and coating the molds with beeswax.

DL: Isn’t that funny? Comme les Français.

PW: But I’ve had that same situation with Turkish women. They’ve said, “Don’t tell my neighbor the recipe, but you can have it.”

DL: Now, I understand you couldn’t boil water when you first got engaged. Is that true?

PW: I made only two dishes at the time: pork with banana sauce and something else. Then my mother offered to pay for me to learn how to cook properly.

DL: You went to Dione Lucas’s Le Cordon Bleu Cooking School [at the Dakota on West 72nd Street.]

PW: Yes. I took six lessons with Dione for $50, and I was hooked. I left college because of it. After those six classes I said to her, “I love this but I can’t afford anymore.” So she said, “If you work for free — setting up, filing…”. And I said, “Absolutely!” And I worked for her five days a week, 10 or 12 hours a day.

DL: And you quit college to do that. What were you studying?

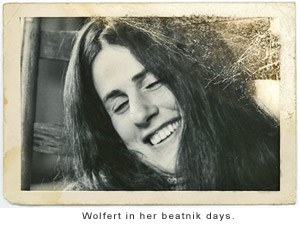

PW: [laughs] Twentieth-century literature. My mother was appalled that I wanted to be a cook, but my first husband, Michael Wolfert, enjoyed the idea. He liked to go to parties and say, “My wife’s a chef.” And I really wasn’t one, but do you know how many people turned their back on me? All the Harvard, Radcliffe, Columbia, and Sarah Lawrence people just looked at me with a sneer. But Michael enjoyed it, because it was offbeat. We were of the beatnik generation. I wore all black and had long hair [laughs]. On the other hand, I wasn’t very responsible: I spent all our wedding money — all $3,000 that were given to us — on things like the proper dish for serving pheasant under glass. It was heaven buying all the equipment. In fact, I bought my first clay pot back then. It was a triperie, and I didn’t even know what tripe was, but I loved the feel of the earthenware in my hands.

DL: You’re working on a clay-pot cookbook, aren’t you?

PW: Yes, it’s called Confessions of a Clay-Pot Junkie [since retitled to Mediterranean Clay Pot Cooking: Traditional and Modern Recipes to Savor and Share — ed.]

DL: Hmm…who’s publishing it?

PW: Wiley. I was going to call it Jack Kerouac Told Me I Had Great Legs but decided against it.

strong>DL: Now, that title I like. I wouldn’t know what the book would be about, but it certainly tells me a lot about you.

PW: Yes, but the joke is that’s about all he ever said to me.

DL: [laughs] When did you meet Kerouac?

PW: It was when I was studying with Dione. I did some private catering for these very wealthy twins who lived on Fifth Avenue, right across from the Metropolitan Museum. They had a party, and Alan Watts was there, and Allen Ginsberg (but I knew Ginsberg from the West End Bar), and naturally Jack was there. Oh, and Joseph Campbell, too. I made Dione’s curried chicken. I also went downtown to some of the Indian stores and bought Bombay duck and put it all out so that it would have a curry feeling.

[After her one-year stint with Lucas, Wolfert worked with James Beard. She also catered and was the sous chef to John Clancy at the restaurant Chillingsworth on Cape Cod. Then she moved to Morocco in 1959.]

DL: What drew you to Morocco?

PW: Well, Michael and I both wanted to be writers, and that’s where writers went in the ’50s and ’60s. It was cheap, too, so writers and artists could afford to live there.

PW: That and also my husband’s family knew [the poet] Muriel Rukeyser, who wrote us a letter of introduction to Paul and Jane Bowles. Paul thought we could get jobs at this little international school, which we did.

DL: Teaching English as a second language?

PW: Well, no, it was a little international school subsidized by the Friends of the Middle East, which was financed by some mysterious U.S. agency. It was set up to finance and help educate the children of the revolutionaries, who were trying to overthrow the French government. My husband became a teacher, and I worked in the library. After a year we left, because not only did Moroccans go to this school, but also ex-Nazis. We spent a year traveling around the Mediterranean before heading to Paris.

It was 1961, and we lived in the Beat Hotel on rue Git le Coeur, and Brian Gyson, the creator of the Dream Machine, was across the hall, and William Burroughs lived upstairs. We stayed in Paris for eight years and then went back to Morocco in 1968.

[In 1968 Wolfert and her husband divorced. She returned to the States in 1969 determined to begin a career in food.]

DL: After you returned home, what happened?

PW: For the two years I lived in New York, I worked on a project for CBS called International Home Dining. It was a mail-order box filled with ideas for a theme dinner party, with music supplied by Columbia House. For example, for the Greek dinner, in addition to recipes and ingredients, we supplied drawings on how to do a Greek dance. I also inquired at a Greek church where to find a brickie, who is a woman who reads coffee grounds. I brought a photographer with me, went out to Brighton Beach, and interviewed her while she read my grounds.

During this time, the famous restaurateur Tony May hired me to organize culinary fortnights at the Rainbow Room. We had a Spanish fortnight, a Greek fortnight, an Italian fortnight. I did everything — I even brought different chefs to the restaurant. It was 1970 and we had women from Puglia on the 65th floor of the Rockefeller Center making orrechiette with their thumbs. Then I moved on to a Mexican fortnight, which is when I met Diana Kennedy.

DL: Up to this point, how much cooking training had you had?

PW: Just a year with Dione and six months under Beard’s culinary guidance.

DL: Okay.

PW: Tony paid me a $100 a week to organize the fortnights, which was good because I had two kids to support, and the CBS job wasn’t enough. Diana said to me, “Why don’t you do a Moroccan cookbook?” Which I thought was a good idea because I was planning on moving back to Morocco.

DL: Was that because of economics?

PW: Well, there was economics, but I knew the situation with CBS was going to fail, even though I was working with Diana on the project. Plus I had this new boyfriend, Bill Bayer, who would follow me anywhere in the world, so that was easy.

DL: [laughs] They’re always good to have around.

PW: I didn’t know that Diana told Fran McCullough [an editor at Harper & Row who edited Kennedy and Sylvia Plath, among other writers] about me. I went to see Fran, and she encouraged me to write a proposal for the book. She was a wonderful editor. In 1971 Bill, the children, and I moved to Morocco so I could work on the book. Well, Bill took care of the children with the help of some servants, and I moved into the home of a woman who used to be a dada to the grandfather of the now-presiding king.

DL: A dada is a chef, right?

PW: A chef, a great cook who runs the kitchen. She was in retirement, but the Moroccan government paid her and paid for the food while I lived there for six weeks.

DL: The Moroccan government paid?

PW: Well, part of the government. Some of the higher ups had an idea that this was going to be a wonderful gift book with lots of pictures. It didn’t quite work out that way because Harper & Row didn’t think they’d sell many copies. By the way, Couscous and Other Good Food from Morocco is still in print 32 years later. I get more in royalties each year than I got for writing the book back then! [laughs].

Anyway, the Moroccans had arranged for people to visit everyday at lunch to tell me stories and to inform me about regions of the country. Meanwhile, I was sending the recipes back to my mother and to my best girlfriend to test. My father couldn’t wait for it to be over, he couldn’t stand the food! While I lived there, I went around the country, and the kaid, or the sultan or the mayor, was told to find the best cook of a traditional dish of the town and to teach it to me.

DL: God, were you lucky.

PW: It was an absolute gift. I really got into it. I was dressing like a Moroccan [laughs]. The picture of me on the back cover [of the book] is how I went around all the time.

DL: Very exotic.

PW: Tangier was a very exotic place. I wanted to continue living there but there was no “Son of Couscous” to write. The city was full of people from all over. In 1973 a huge number of Lebanese started pouring into the country, because it was the beginning of the Lebanon war, and I befriended a lot of them. That was how I decided to do another cookbook, Mediterranean Cooking [published in 1975], which is based on ingredients found around the Mediterranean and how dishes move from place to place. I didn’t go back to America after the publication of the book to enjoy the success — all six people who bought the book. Two years later, though, we did return home because my kids were ready to go to high school. It was then I discovered that there were people in different cities who admired my Moroccan cookbook and wanted me to visit and teach. So the next step was to become a traveling teacher.

This was the time I met Barbara Kafka, who had started Cooking Magazine and then The Pleasures of Cooking. She encouraged me, so in every issue she had a picture of me doing something. Meanwhile, George Lang [owner of Café Des Artistes in NYC] took a liking to me and sent me to Manila to set up Filipino food at the newly renovated Manila Hotel. He sent me because he felt anyone who could crack Moroccan food the way I did could crack Filipino food. Only, I got there at a time when there was a terrible typhoon, and we were all under house curfew for weeks.

DL: Did you crack it?

PW: I doubt it. But I was fortunate then: Everyone wanted to help me. Kafka, Lang, Gael Greene. I had more mentors than I knew what to do with. Later Michael and Ariane Batterberry had just started Food & Wine, and they were aware I knew [pastry chef] Gaston Lenôtre, because I had worked with him. So they sent me to France on assignment to study with him, and they added, “By the way, would you mind going down to southwest France to learn about cassoulet?”

DL: The proverbial offer you couldn’t refuse.

PW: Exactly. So that’s when I moved to Gascony and met the Daguins. I moved in with them while Bill took care of my kids. I think I took 25 trips over the following five years, and that’s how I wrote The Cooking of South-West France. At that time I was always teaching and writing. In fact, South-West is made up entirely of previously written articles. You can’t make a living in food writing unless you develop a recipe that you can put into an article, put into a book, and teach in cooking classes around America. That’s for the nascent food writers out there.

DL: I’m sure they’ll appreciate the advice, bleak though it may be.

PW: This is the same time of the food-writing hub at Le Plaisir, a restaurant in New York. On Saturdays, writers such as James Beard, James Villas, Barbara Kafka, Suzanne Hamlin, myself, and others would lunch together to talk about food. Masa was the chef. He would create all sorts of exciting new dishes for us to taste. [He went on to make a name for himself in San Francisco in the ’80s, and then was tragically and horrifically murdered.]

DL: That was the late ’70s, right?

PW: Yes, about 1978. My boyfriend, Bill Bayer, walked out on me because I spent more time with food people then with him. At the same time, Pat Brown, who had just been fired from Bon Appétit as editor-in-chief, came to New York to start Cuisine. She needed a place to live, and since I had a spare room, she moved in. And for three years, we’d talk food over the breakfast table. I had a lot of cover stories.

DL: Well, I guess you could say that came from sleeping with the editor — so to speak.

PW: [Laughs] I got her so excited about things, and she cared. She and I are very close to this day. Then she went on to HarperCollins, and Bill and I got back together and married. Around this time I started to look for another book to write. I went to Catalonia only to run into Colman [Andrews, editor-in-chief of Saveur], and he told me he’d almost finished Catalan Cuisine: Europe’s Last Great Culinary Secret. I then went to Sicily. In 1988 World of Food came out and was a result of floating around the Mediterranean — plus excursions into Alsace. Unfortunately, it bombed, and John Thorne attacked me because I said I was in love with “the big taste.”

DL: Define the big taste.

PW: It’s that extra something that makes a dish special. A dish that is deeply satisfying and so good that it appeals to all the senses. Many, many recipes read as if all you need to do is put everything into a pot and let it cook.

DL: Which is very pedestrian.

PW: That’s my point. Yet there’s always someone who makes the same dish as everyone else but who does something special that gives it a unique thumbprint, giving the dish more complexity, more refinement, more memory, more everything. A French writer once said “a recipe has a hidden side, like the moon.” In every recipe there’s a little something that makes it special, and, hopefully, better. And that’s what I was looking for. It’s not good enough to just go to Turkey, bring back a bunch of Turkish recipes, and write a cookbook or an article. These recipes have to be not only good but have a story that can be told about the whys and the wherefores behind the dish.

DL: I’ve discovered these types of recipes almost have to have a specific culinary DNA attached to that particular cook. Hopefully, a good one.

PW: Hopefully the best one. When I go places, I always ask, “Who’s the woman who makes the best this or that?” and all the eyes go in one direction. I always know where to find those cooks.

DL: And I’ve heard that you’ll knock on doors and try and seduce the recipe out of these cooks.

PW: That’s an exaggeration. I’m being introduced. They know who I am. I used to spend six months in preparation for an article.

DL: That’s excessive, not to mention unprofitable. How did you survive financially?

PW: Because I’d teach people how to make the recipes, and then I’d publish them in a book. That’s how I’m writing my clay-pot book. Clay pots have stories to tell, and I’m a storyteller. That’s my job. If my stories can place a dish in context and make it come alive so someone will want to cook it, I have achieved something special. So, you know what? Twenty-five people can use my idea for a clay-pot cookbook now that I’ve mentioned it, but they won’t be creating my book.

DL: Because it’s your voice, it’s your opinion, and it’s your stories.

PW: Right. I feel that way about all my books. I have common threads throughout my books, including cooking techniques such as slow cooking, attaining richness without heaviness.

DL: Okay, let’s talk about your dichotomous nature. You have so many well-documented phobias: You’re afraid of dogs, of germs, yet you’ll pour an elixir made from fox urine into Armagnac to quell anxiety. Or you’ll troop through the remotest parts of the Mediterranean, where at least an American model of hygiene doesn’t exist. It just doesn’t make sense.

PW: Oh, of course it does. I’m careful, that’s all. I go everywhere, I’m just particularly careful.

DL: You check your demons at the door when you arrive in the Mediterranean.

PW: I’m not afraid to eat on the street. I’m afraid of the plate they serve food on, and if I have to eat from a suspect plate, I’ll eat from the center of the dish. And I’m not afraid of dogs anymore, by the way. I get over my demons. I don’t let them take over my life, but I have had them, and I’ve played with them and I used them to propel me.

DL: And they’ve never stopped you, especially working with people you’ve only just met?

PW: No. You know, thank God, nothing has ever happened to me when I’ve gone into people’s homes. But I sort of can tell. I’ve been very lucky.

DL: I think you have been.

PW: It’s looking at things from another angle. People say to me, “How do you get in?” “Bring presents,” I say. That’s the secret.

DL: Ply ’em with gifts.

PW: You do. And you kiss each woman on each cheek, and you touch your heart. Then she’s at ease.

DL: And she welcomes you into her world?

PW: Oh, completely.

DL: I have this sense that you take on lovers, and of course I’m talking about your books. And are they indeed like lovers to you, in that you get so wrapped up in them all else falls away?

PW: Yes, yes, absolutely! Did you notice on my Web site where I mention I won’t publish a recipe until I’ve had my way with it?

DL: Yes, I did.

PW: [laughs] But I’m a very loyal lover.

DL: So it’s serial monogamy with all these different books. How does your husband handle your infidelity?

PW: He’s a little jealous. Right now, though, he’s very proud of me.

DL: That’s good. When you return from an overseas research trip, these culinary trysts, do you consider it your job to be a social and culinary scribe, faithfully documenting every aspect of your work?

PW: No. I don’t think of my recipes as documentation because I want to convey the integrity of a dish. To that end, I’m certainly willing to change them to make them work and taste better. I believe it’s my responsibility to work on a recipe so that after people have made the dish they’ll say, “This wasn’t a waste of time.” And, hopefully, it’ll give them an accurate taste of that country’s cuisine.

DL: I agree with you. Part of my wanting to interview you was that you inspired me to finally visit my family’s homeland, which is the Azores, in Portugal. Your enthusiasm and respect for other cultures gave me the framework I needed to start deconstructing the romantic fantasies of the “old country” that I had gathered over the years. You also gave me the methodology to start collecting the recipes from my family and my heritage. With all your research and travel over the past 45 years, do you think true foreign cultures still exist, or is the Americanization of the world destroying what makes traveling and eating abroad so pleasurable? So different?

PW: Absolutely not. Good food in Portugal or in Italy or wherever is taken as a natural prerogative. If the Portuguese or Italians are still eating a meal together, they’re preserving their food culture. I went into homes in Tunisia, and while we had dinner the television was on — but we were eating a meal together. I think it’s still the norm in the Azores, and other places, that people all sit down together at least once a day to eat.

DL: It’s true of the Azores, I know that.

PW: And I bet kids there are gastronomically literate, too.

DL: But what bothers me is when I went to the supermarket, there were one or two bottles of piri-piri sauce [traditional Portuguese hot sauce] alongside bottles of Tabasco.

PW: Well that’s the EU. The EU has destroyed everything.

DL: And people are reaching for Tabasco instead of piri-piri because it’s American.

PW: This is why, more than ever, you need to write these things down because Portuguese food and culture has to be preserved, just like ours does. We in America are trying, through cookery books and other things, to recreate some sort of lost culture. But I’ll tell you the real problem here: We have cookbooks, we have newspaper and magazine columns, we have you, we have me, we have fancy-food shows, we have eGullet — yet we have the fastest-growing convenience-food industry in our history…

DL:…which is pathetic.

PW: It is pathetic. Everybody is interested in food, but they’re not really interested in cooking it. They don’t want to do it, because it isn’t native to them. Did you know in France they have this event called Le Semaine du Goût? [During this Week of Taste, chefs either go into schools to introduce children to various foods or invite the children into their restaurant kitchens to cook simple dishes.] They have that, and they’re safeguarding it. Alice Waters is trying to create something like it with her schoolhouse programs, but for the most part, not many people are making an effort here.

DL: I agree completely.

PW: There’s a decline in cooking skills. We have to teach people to stop thinking of eating as a pit stop. Americans have to sit down with their families, and once they do that, they’re going to want to eat together, and then they’ll perhaps start cooking a little bit. It can’t be the other way around — people starting to cook first — because they don’t want to cook; they just like to read about food. They’re intellectualizing food. Sadly, all they know is restaurant food.

DL: I don’t think a lot of restaurant food is meant to be cooked at home. Or rather, I don’t want to go to a restaurant to eat food I can make.

PW: Well, chefs can teach us a lot. I love sophisticated kitchen techniques. I’ve known chefs who have reinterpreted peasant dishes and raised them to new and glowing heights. Still, $30 is a lot to pay for a plate of braised oxtails.

DL: It’s all about marketing. I remember when things like osso buco and monkfish were consider peasant food — even junk food, if you will. Speaking of junk food, have you eaten in a fast-food restaurant?

PW: Yes, and you’re in for a big surprise because it was one of the most shocking food experiences of my life. I went to teach in Durham, North Carolina, at the home of Judith Olney, the sister-in-law of the great Richard Olney. Judith picked me up at the airport, and on the way home we had to stop to feed her kid. So we went to McDonald’s, and I ate some fries.

DL: What did you think?

PW: They were good. I’ve also had Burger King once or twice in my life. I don’t eat fast food, but I’m not a person who brays to anyone within earshot, “I’ve never been to Wendy’s. I’ve never been to Dunkin’ Donuts.”

DL: But you do have things that peeve you.

PW: Sure. I was on the plane yesterday, and my biggest worry was dinner. My choices were pasta or chicken, and I kept thinking that the chicken was going to be Tyson’s or something disgusting. Then they announced that the people at the back of the plane — where I was — might not get their choice. And I kept saying, “Please, please make it pasta for me.” That’s what I spent the better part of the flight praying for because I was afraid I’d have to put a piece of Tyson chicken in my mouth. And that’s the kind of neurosis I have.

DL: Okay. We’ve talked about your past…

PW: [laughs] Ha! I’m a woman with a past!

DL: …and your methodology, accomplishments, even Tyson’s neurosis. What about the failures? What are the biggest criticisms that have been leveled at you?

PW: That my work is complicated and fussy.

DL: That the lists of ingredients in your recipes are insurmountable.

PW: Well, that’s just in South-West France. How can you make cassoulet or garbure or any of the other great daubes and soups of the French southwest with less than 15 ingredients?

DL: Jim Villas has been open about his frustration back then of having to track down preserved lemons, squid ink, fenugreek, Aleppo peppers, and pomegranate molasses when making your recipes.

PW: I am not a faddish cook, but when a new ingredient, a true ingredient comes on the market so that my readers can finally make the true dish, I want to encourage them to use it. When I wrote my Moroccan cookbook, I made no compromises. I called for cardoons when there were no cardoons to be found here, yet I found them. I found them among Italians, and they gave me some to test.

DL: Did you give sources?

PW: Yes. Not for the cardoons, but for the spices and everything else in the book. What’s interesting is the pomegranate molasses, the Aleppo pepper — all those things you just mentioned — are common now. Somebody had to write about them. I was one of the writers to start the ball rolling.

DL: Do you think as time has gone on that you’ve acquired more readers who understand what you were doing 30 or 40 years ago?

PW: Yes, but a lot of them think I’m a maniac. When one critic reviewed Slow Kitchen, I think she referred to me as “crazy” [laughs]. It’s not crazy, it’s just my own take on it, whatever it may be.

DL: Is this notion of slow cooking and slow food an evolutionary or a revolutionary step for you?

PW: The truth is, if you look at my Moroccan cookbook, I’ve been slow cooking all along. All through my books, it has been my favorite way to cook. It was just that this was the moment to use the word slow in the title.

DL: So it had nothing to do with the slow-food movement? No piggybacking on the sudden popularity of the movement?

PW: No, no, no. Not at all. I do talk about the slow-food movement in my book, but just to differentiate and show you the similarities. Actually, I was going to call it Mediterranean Slow and Easy, but with me nothing’s easy.

DL: [laughs] Ah, so you agree with your detractors?

PW: Well, my publishers do want to sell books!

DL: If you had a mantra, a message that you wanted to get across to readers, what would that be?

PW: I used to have one, and now I don’t. Basically, I like to explain food. I want to teach you how to coax it, push it, bend it, and make it come alive. That’s the pleasure that I want people to get from my books. My job is to ask questions.

DL: It seems to me that The Slow Mediterranean Kitchen is a perfect book for beginning cooks because there are long, mostly unattended cooking times. Plus there’s a wide margin for error that could attract new readers and new cooks.

PW: Yes, but you need time, though, to cook from this book. Even with my Moroccan cookbook, everything takes three hours, and that’s how long a meat tagine takes, period. You can’t argue the point. It needs that time to mellow, to turn into something better than the sum of its parts. I’m interested in culinary adventures and sharing them, and The Slow Mediterranean Kitchen is the story of people and places. Sometimes I even tell you why something works.

DL: Every cookbook has a theme, otherwise, it’d be very hard to market it to the public. But your themes — from your first adventures in Morocco with Couscous through South-West France, and now with Slow Kitchen — feel deeply personal. To me, they almost serve as a personal journal of one woman’s life.

PW: Yes, my books are a continuum. That’s why I stuck mostly to the Mediterranean.

DL: This is the last question, and one I think you’re uniquely positioned to answer. There’s so much controversy surrounding culinary authenticity. At times, I’ve been called to the carpet because a particular dish that has been in my family for generations has been called “faux food” by someone whose family makes it a different way. And in the Azores, the same dish can vary from town to town, neighborhood to neighborhood, even family member to family member. To you, what’s an authentic dish?

PW: Their way? Your way? What’s authentic? Nothing. I veer away when anyone says the word authentic, because authentic isn’t what I’m interested in. I’m interested in the truth. There’s a difference between the two. The integrity of the dish is important, but I’ll change the recipe to make it work. Integrity is using the ingredients of an area, it’s using what people recognize as what comprises the dish, but there’s not just one way to make something. Even Bordelaise sauce has seven different ways to make it.

DL: Point taken.

PW: The recipes in all my books are, for lack of a better word, authentic in that they were taught to me by locals, but there are people down the road from where I would be learning a dish who cooked it differently. I just try to make it as good as I can and frame the recipe in a story. It is all authentic.

DL: Well, the reason why I asked is I took the idea out of your introduction, where you wrote, “Authenticity is always my guide, but I try not to let it become my straitjacket.”

PW: Oh, okay, that’s different — it’s a guide. I’m trying to get to the truth of a recipe to use the right ingredients, the things that people generally agree comprise the dish. But how they make it is personal.

DL: So it’s being selective within an area.

PW: Exactly, and that’s why I said it’s not a straitjacket, because with a straitjacket, I’d have to go with the first person who said, “This is the way of doing it.” Well, how would I know if she knows, and does she know which is the right way? Does anyone know which is the right way? It’s all subjective. Isn’t it?

Paul, thanks for writing. If you read carefully, she doesn’t say she invented anything. She clearly says she was given access to the original recipe, which states the molds are lined with beeswax. What she did perfect was making it for American cooks who don’t have access to the same types of ingredients as French cooks, which is why she calls for cake flour.

If the photo shows overbaked cannelés, well, that’s my fault. It was all I could find at the time. Any suggestions of photos of perfectly baked cannelés are welcome.