For a long time, every year when it came to the interminable turkey-eating season—November to New Year’s Day—I stood there holding a meat thermometer, hands trembling, face twitching, wondering if this bird would be the one I actually cooked correctly. You see, it seemed no matter what I did, I missed the thickest part of the turkey thigh so spectacularly that, for a while, I left the protein-cooking part of the day in The One’s hands and I took up the immensely less intimidating baking portion of the entertaining program.

But not before one memorable Thanksgiving when I had to call our friend Matty, a former butcher, into the kitchen to salvage the bird, not to mention my flagging self-esteem. (To his great credit, Matty, a man who’ll use anyone’s misfortunes as grist for a few minutes of hilarious stand-up cocktail chatter, never breathed a word of it to anyone. At least, never in my presence.)

What happened was the bird was done an hour before it was supposed to be. Or I thought it was. The guests had already arrived so I made some excuse about setting the timer incorrectly and corralled everyone into the dining room before they even had a chance to enjoy a glass of wine and my homemade bow tie cheese straws. Then, when I carved the breast (thankfully in the kitchen), it was like watching a scene from Saw V–bloody hell.

Apparently, in my haste, I had pushed the digital thermometer into the thickest part of the thigh and right on through the other side and into the bird’s unstuffed cavity. There, the probe became superheated super-fast, not giving the turkey enough time to roast properly. So I shooed everyone back into the living room (except Matty), and we reassembled the bird, stuck it back in a slow oven, then all of us had to make that one bowl of bow tie cheese straws and some roasted Marcona almonds last an hour.

My problem was: How to tell where the thickest part of the thigh was so I could jab a thermometer into it? It seemed like a no-brainer, but without an arthroscopic camera attached at the end of my thermometer’s probe, I was lost. Then I discovered an absolutely surefire way of hitting that sweet spot every time, and my birds have been perfectly cooked ever since.

How to find the thickest part of the turkey thigh

Go ahead and roast your turkey using whichever method suits you. To take its temperature, remove the beast from the oven after 30 minutes and stick the thermometer into the thigh. I use an ovenproof digital thermometer with an alarm so I can monitor the temperature during cooking. Now, jab around in there, you’ll see the temperature rise and fall. Find the coldest spot. That’s where the least amount of heat has penetrated and therefore it’s the thickest section.

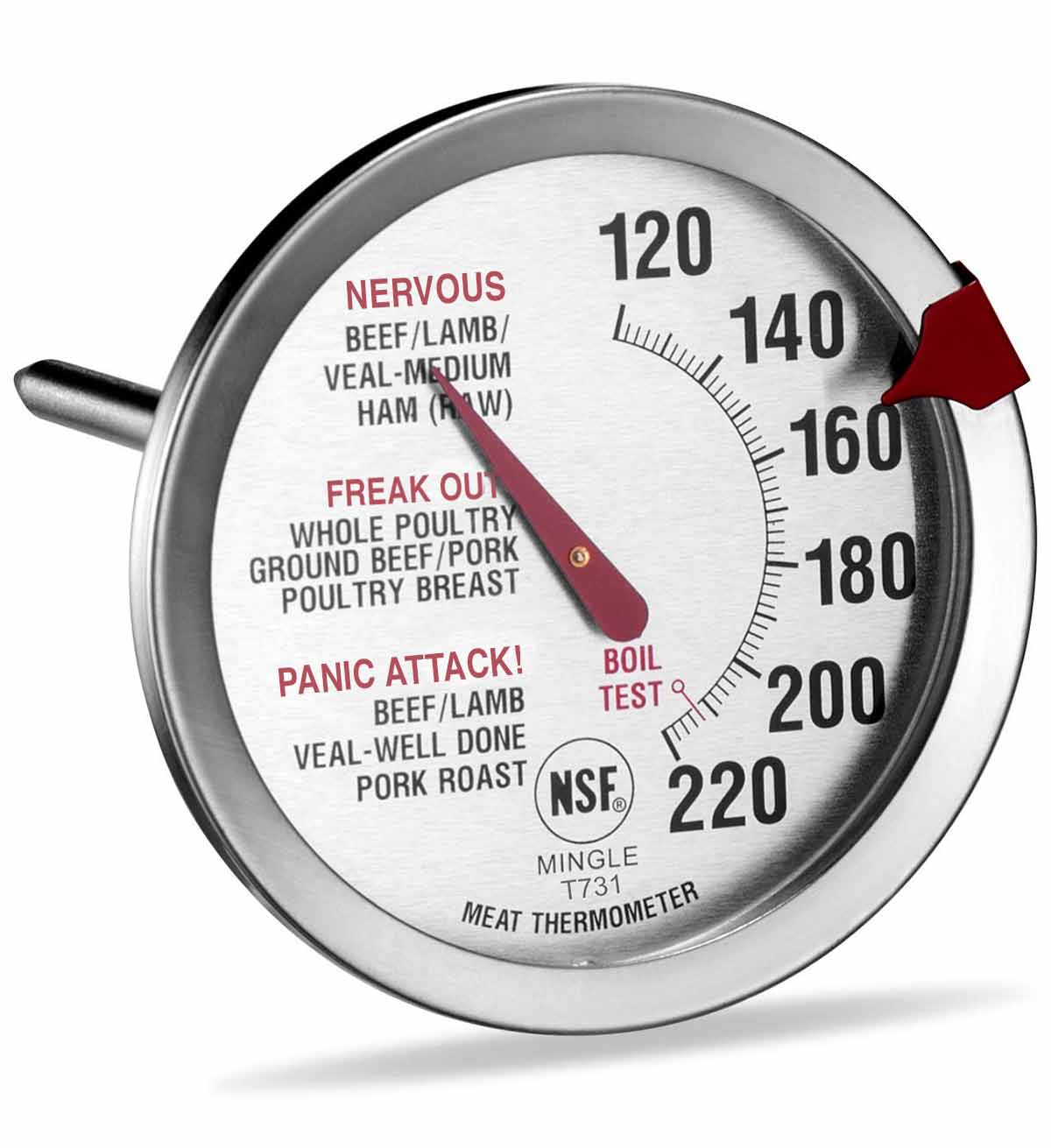

Leave the thermometer where it is, slide the bird back in the oven, and wait until the desired temperature is reached. I go with 165°F (72°C). I feel comfortable with that. For the longest time the USDA said 180 to 185°F (82 to 85°C) was the proper thigh temperature, and the result was a bird that was chokingly dry. But in 2006, the department mercifully revised its temperature rules, which means we all have a chance for a better, juicier turkey.

Of course, they still demand a high 160°F (71°C) for medium pork, but I never go above 145°F (63°C), and, hey, I’m still here. But that’s another story best left for a different holiday. Originally published November 9, 2008.

Thanks, David. I always have trouble finding the right place for the thermometer. Have a happy Thanksgiving.

Jackie, I hope this helps! The One and I wish you a wonderful, loving, and tasty Thanksgiving.

I no longer strive for the Norman Rockwell style of whole roasted turkey. After 42 years of making turkey, I have settled on two techniquest that are foolproof:

1. Spatchcocked and dry brined and cooked on either a smoker of two zone charcoal grill. The uniform thickness of spatchcocking renders the thickness question moot.

2. Breaking the bird down, dry brining, and cooking the white meat and dark meat separately to their respective temperatures sous vide before hand. Then before meal time, a quick trip to the grill to warm up and develop some color and crisp skin.

Bkhuna, you’re a better cook than I! That’s a lot of work. Actually, this year I said to The One I wanted to spatchcock the turkey and he was vehement in his, “NOOOO!” So that unattainable Rockwell turkey will once again elude me, as he wants a buxom beauty to be brought to the table whole.

If one insists on a whole bird, the kind folks at Thermoworks have a great article. I hope sharing this link isn’t a violation of good etiquette.

Bkhuna, in this case, you’ve offered a very helpful article, so no violation! Plus, as far as I know, you’re not a shill for Thermoworks, so we’re good.

I have hosted Thanksgiving for thirty years…that means, of course, thirty turkeys that I never enjoy eating. I have tried just as many suggestions with varying results, though everyone feels compelled to say that every turkey was delicious. I would have welcomed your suggestions this year, however, I’m making a filet of beef instead! Happy Thanksgiving!

Angela, why don’t you like your turkeys? My dad doesn’t like turkey at all, so we always had either capon, ham, or a beef roast.