Jump To

During a friend’s recent visit, the subject of the Kitchen God (Jou Gwun in Cantonese) came up in conversation. Since I’m Chinese and a food writer, she assumed that I would have an altar in my kitchen. My friend was genuinely alarmed when I told her no. Even though I was aware that the Kitchen God oversees the activities of the kitchen, it wasn’t until that moment that I understood what perfect sense it made for me to have my own altar.

The Chinese feel that the heart of a family resides in the kitchen and that when its members are properly fed and nourished, they will be content and have abundant energy to work hard and prosper. The Kitchen God, also known as the God of the Hearth, is the official guardian of the family. Traditionally, his altar is located just above the stove, a position from which he can watch over the family’s conduct and where incense and offerings are made.

The Kitchen God’s most critical role comes before the Chinese New Year’s celebration. During the propitious period, seven days preceding New Year’s Day, he ascends to heaven to present his annual report on the state of each household’s affairs to the supreme spiritual being, known as the Jade Emperor. My Uncle Sam describes the Kitchen God as the “connecting link between God and man, and the censor of morals.”

Prior to the Kitchen God’s ascent, the traditional Chinese home is thoroughly cleaned, and sweet offerings are made to coax his influences. With his favorable report, a family can expect good fortune and auspicious blessings in the coming year.

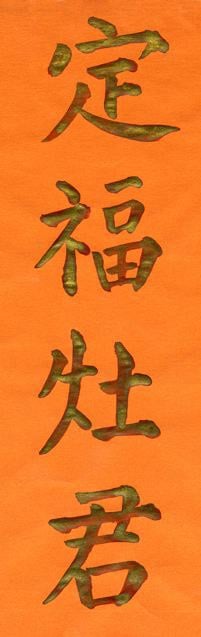

Not long after my friend’s visit, I set off to Chinatown in search of a Kitchen God altar. Since I live in New York City, this journey was merely a matter of a half-hour walk. I went directly to the temple supply store on Mulberry Street. I chose a simple red wooden plaque, about eight inches high and four inches wide, on which the four Chinese characters, “Reserve Fortune Kitchen God,” were written exquisitely in gold. The altar cost about five dollars and included small rice wine cups and incense. The clerk reassured me that my Kitchen God would not only improve my fortunes, but protect me from kitchen disasters, provide extra nourishment, and make my cooking more delectable.

Who could resist?

As I prepared my altar, I reflected on the Kitchen God’s omnipotence. My Auntie Katheryn had told me that she remembers certain times when women were prohibited from worship of the Kitchen God. My Uncle Sam recalls watching my grandmother arrange the incense and food offerings, after which she would ask one of her sons to bow towards the sky. Surely, I could trust that by now the Kitchen God’s views were more inclusive.

A week before Chinese New Year, I thoroughly cleaned my home. Then I placed a bowl of oranges and tangerines as a sweet offering to the Kitchen God. I also poured him three small Chinese cups of rice wine, enough for him to get a little drunk. I lit the incense, regarded as soul food for the Gods, and watched as its smoke enveloped the plaque before making its heavenly ascent.

Coincidence or not, good things began to happen. Three presentations I had been anxiously concerned about went smoothly; new job opportunities were offered to me; and travel invitations came my way. Perhaps the timing of this good fortune was coincidence, but nonetheless, I smiled at my altar every day, happy to share the credit.

Since then, the Kitchen God has become a permanent and reassuring presence in my kitchen. It reminds me to be conscious in the kitchen and in life. Because I continue to interview family and friends on the meaning and protocol of the Kitchen God, I’ve been treated to unexpectedly beautiful conversations about spirituality and graced with remembrances of old China, and I am grateful to be adding ancient rituals to my life that honor my heritage. Fortunately, playfulness does not elude our sensibility: the Chinese acknowledge that the offerings are a bribe to the Kitchen God, that the sugary food is meant to sweeten his report, and that the wine is meant to intoxicate him into forgetting bad deeds—or, at the very least, to slur his words so that the Jade Emperor cannot understand his report. If the year is favorable, many people clean the plaque and reuse it the following year. If the year goes badly, some Chinese replace the plaque to change their luck.

This year, as the New Year approaches, I plan to thoroughly clean my house. Housekeeping is not my forte, but in hopes of a favorable report, I will honor the Kitchen God. I’m confident that it can’t hurt. But it’s also become my custom to make food offerings to the Kitchen God beyond New Year’s. In the winter and spring I offer him the traditional bowl of oranges, in the summer I am convinced he likes peaches and nectarines as much as I do, by autumn I bring him apples from the farmer’s market. After all, a God who protects me from kitchen disasters and makes my food more delicious and nourishing deserves to be given food bribes throughout the year.

Print Your Own Kitchen God Note

The four characters typically found on a Kitchen God plaque (above right) read: “Reserve Fortune Kitchen God.” This calligraphy was written by the legendary Chinese cookbook author and teacher Florence Lin. For more than 30 years, Florence had these characters, framed, hanging by her stove. Many years ago, she generously gave it to me. If you cannot find a Kitchen God plaque, make your own by printing these characters and cutting them out. Once framed, it can be placed by your stove. Fill a rice bowl with raw grains to hold your incense, and your Kitchen God altar will be complete.

Great article! Trying to learn about my heritage and culture so this was super helpful. Is Western Chopsticks still in business? The link isn’t working and I can’t find anything on google about it. Could you also name the temple supply store on Mulberry St? Unsure if it is still there as well. Thank you!

Belinda, sadly, Western Chopsticks doesn’t have a website anymore. I’ve removed the mention of it from the article. I believe the store Grace was referring is KK Discount.

As someone that firmly believes in preserving family recipes and traditions, I found this article incredibly interesting. Thank you for introducing me (and others) to the Kitchen God!

You’re welcome, Jennifer! I’m so pleased that you enjoyed it.

Grace,

This was a very interesting article. We’ve been trying to use the Kitchen God around the new year in my house as my children are adopted from China. But this year my son posed a question I really didn’t know the answer to. What do you do with the food that you offer to the Kitchen God after the offering’s been made? Our Kitchen God alter has a little shelf and we’d been each placing a forkful of food on shelf from our plates at dinner, and then after a couple of days I would throw the food away and start again, but I have the feeling I might doing this all wrong. Can you give me any details on HOW you offer the food and what you do with the food afterwards? Same with the wine. You pour a cup of wine for the Kitchen God and then what? What do you do with the wine?

Josh, The typical food offerings for the Kitchen God is fruit as it will sweeten the Kitchen God. After the Kitchen God has “eaten” the food and the incense is burnt the Chinese are practical enough to then eat the fruit, as nothing should be wasted. Treat alcohol the same way.

In my family when we went to the cemetery to pay respects to our ancestors we would bring a whole chicken with scallion and ginger sauce, roast pork, rice, sesame balls, and 3 small glasses of whiskey (as my grandfather loved whiskey) and make the offering. We would bow, light the incense, and my father would splash the whiskey on my grandfather’s grave. The food would then be taken home and eaten for dinner.