Crying may seem an odd reaction to seeing our Connecticut kitchen demolished, for the second time, in the name of remodeling. That kind of behavior is typically reserved for after the renovation, when you’re sitting alone at your desk, a half-empty bottle of scotch at your side, checking and rechecking the contractor’s bill. But my emotional blip wasn’t out of any lingering affection for our appliances. One of the professional double wall ovens hadn’t worked in years, and the other couldn’t keep its heat up even if Julia Child herself were cooing into its cracked control panel. The cooktop’s vent was broken and its burners sparked incessantly when turned on. And the side-by-side fridge was trapped in a corner, so we couldn’t open the freezer door more than 70 degrees, rendering it virtually useless.

No, I cried because beneath the wainscoting, scrawled in sixth-grader-like handwriting between the zigzag of the well-heeled snake, was a wish I’d long ago forgotten: “Here’s to many great meals! Love, Matty and Janet.”

The moment The One and I had first entered that house in 2006, one of many visits before we finally made an offer, an oppressive energy emanated from the place like a foul odor. That’s when most intelligent buyers would’ve hightailed it to the next property. But not The One and me. Just like those fools in horror movies who trip over the hacked-up body of the head cheerleader and decide to still press on, we stayed, trying to justify our feelings. Being exquisitely attuned to my own melancholy, I’d become sort of a high-fidelity depression detector. And I sensed a profound sadness that penetrated every stud, every floor slat, every door frame.

“You do know what happened, don’t you?” asked Donna, our realtor, in that hushed tone that screams THIS IS KILLER GOSSIP!

“No, what?” I asked, saucer-eyed. The One, who prides himself on eschewing gossip, demurely turned away, although I knew every un-Naired hair on his back was listening.

Donna grabbed my arm and pulled me close. I smelled Aussie shampoo and garlic. She whispered that one night several years ago, Caroline, the seller, got a phone call from her husband telling her that his shift was ending early and he was on his way home. But he never made it. He was killed in a head-on collision on a windy back road five miles from home.

“Donna,” I asked, “what does all this have to do with this house?” I thought of Caroline’s dead husband haunting the place. Or of blood weeping from the walls. (After all, one of the bedrooms was a shocking red.)

She waved off my question as if she was batting at a mosquito. “She moved here after he died.” Noticing my confusion, she whispered, “This whole place is a mausoleum. A tribute to him.” She paused dramatically before continuing. “Look at the kitchen. She put in all professional appliances,” Donna continued. “She didn’t cook. This is the house he wanted.”

Then I understood the sadness. Living here, trying to honor her husband, Caroline had been trapped in grief like an insect in amber. That explained the family room, whose wood planks and window frames were chewed by the dog, and the horrible condition of the yard, its gardens overtaken by thorn bushes and trees nearly strangled to death by vines thick as forearms.

I wanted to respect the former occupant’s loss, although I didn’t want to be saddled with it. I’m not a good Ghostbuster. The last thing I needed was to suck up her sadness like an emotional wet/dry vac.

So a week after we closed on the house, we threw a demolition party, inviting our closest friends to wander through the empty rooms and celebrate with us. On the stone patio was a jury-rigged table bowing under the weight of bottles of champagne and platters of food—none of it made by us, as we hadn’t moved in yet. The One had swung by The Pantry, the local gourmet takeaway shop, and picked up a quiche Lorraine, some tubs of egg and tuna salad for sandwiches, and a berry pie. As we refreshed glasses, gave tours, and tried to assure everyone that the red room was not, indeed, a portal to hell, we also passed out pencils.

“What are we supposed to do?” sniggered Matty. “Take dictation?” They all laughed.

“As if you could spell,” The One shot back.

“Most of you are our dearest friends,” I said, directing my sarcasm at Matty. “And before we rip the house apart, we’d like you all to write well wishes to us.”

“Where?” asked Ellen.

“Everywhere,” replied The One. “Every room, every surface.”

The One and I had talked it over and decided we didn’t want our friends or future guests ever to sense that wall of sadness I’d experienced, a wall so thick one could almost lean against it. We wanted a happy home. And we could think of no better way to achieve that than to infuse it with the love of our friends.

Balancing plates and glasses in one hand, everyone, including The One and me, took to the house. Some scrawled their well wishes in huge block letters a foot high, others scribbled hopes for us so small you had to lean in to read them.

“Hey, dis is like when I was a kid in da Bronx and I wrote graffiti everywhere,” said Matty with that cackly laugh of his. Janet chided him, shaking her head at the rest of us, as if to say, “Ignore him.”

Ellen was busy writing in out-of-the-way places, like the edges of window frames. I knew that she’d studied feng shui, so I made a mental note to check the importance of windows on a house’s energy.

Later that afternoon, as The One and I walked through the house picking up empty paper plates and plastic glasses, we stopped every so often, heads tilted like a pair of hard-of-hearing cocker spaniels, to read the wishes and wisecracks. “What’s this say?” one of us would ask, pointing to someone’s indecipherable scrawl.

The kitchen walls were festooned with messages—including the one from Matty and Janet—that foretold many fine meals, if I do say so myself. Someone (I think it was Ellen) was cheeky enough to put in a dessert order for my lemon curd cake, the request angling up the wall behind the back door.

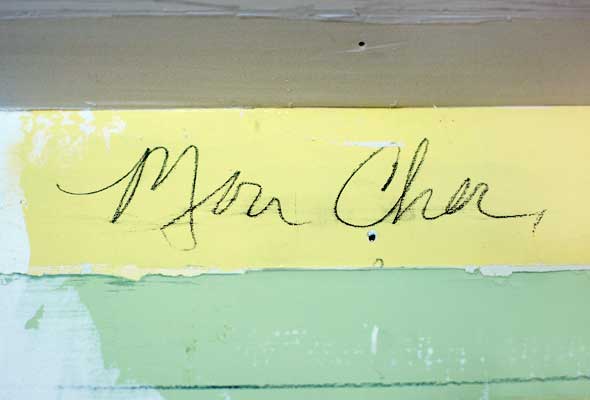

It even seems The One had written a message to me in his movie-star handwriting above the door to the dining room—the holiest of holy passageways—although all that was revealed beneath the ripped-out molding was “Mon Cher.” I must have missed it all those years ago, because last week as I stood on the ladder squinting at it, I simply couldn’t remember the rest. I felt like I had lost an old photo that didn’t have a negative.

In my writing studio, beneath the new cappuccino-colored paint, still lie various wishes for a lifetime of creativity, joy in my work, and pots and pots of money. (The One wrote that. I do remember that.) The living room walls, in a cool, relaxing Benjamin Moore Labrador Blue, conceal wishes for nights of warmth, laughter, and excellent Cognac. There’s even a message from then-unborn Zöe, now the six-year-old granddaughter of our friends Deborah and John, telling us how much she can’t wait to visit. The bedroom is packed with witty and, of course, smutty suggestions, not to mention a few somewhat explicit—and flatteringly out-of-proportion—illustrations. Thankfully, seven years later, most of our friends’ wishes for us have come true.

Last week, as I stepped over sawed-off strips of plywood, bags of dirty pink insulation, and an obstacle course of electric tools, I found myself in front of the only wall in our once-again demolished kitchen whose wiry guts and water-stained two-by-four ribs weren’t exposed.

“What’s that?” asked Dan, our contractor.

“Oh, nothing, really,” I said. Peeking out from terribly out-of-date Martha Stewart-green paint was the word “Deborah.” That’s all. I couldn’t read the message above her signature because it was hidden beneath the swath of green. I’m sure it had something to do with our cooking club.

One Saturday every month Deborah, John, The One, and I, fueled by more than a few bottles of wine, would cook and kvetch all afternoon. Dinner, which was never truly the aim of the day, was eventually served to a ragtag mix of guests—whoever was in the country that weekend. One time we fussed and fidgeted endlessly at the now-destroyed counter over a prime rib recipe from Food & Wine. I can still see us huddled at the dismantled island, poking the meat with our fingers and a thermometer, trying to figure out if it was done.

“Damn it!” I shouted as John, always the carver of the group, cut into it. It was overcooked.

“Oh, who cares?” said Deborah, waggling a plate on her head as if it were a top hat. “Let’s eat!” As long as she was eating, she was happy. And Deb was always very, very happy.

What none of us knew back then as we celebrated our new home, fanning ourselves with paint sample brochures and getting buzzed on Champagne, was that Deborah would be taken from us not a year later. With my back turned to Dan and his men, I stood there for I don’t know how long, tracing her name with my finger again and again.

Before these walls are plastered with subway tiles and a roll-on coat of chic Benjamin Moore gray-green paint (sorry, Martha), I think I’ll once again write The One a message of my own—one right on top of his forgotten good tidings above the dining room door, an invisible, ever-present wish for happiness, love, and much, much chocolate cake.

Dear David, I read your musings with a laugh and a tear.

I too have lived through a reno–“double your budget, and if they say six weeks count on a minimum of 12”-–but I lived–bitched and complained the whole time–but I lived.

My (Italian) father, build our house himself–brick by brick over four years, and-to-date (two years because once you start a reno–it is like plastic surgery: you make something look pretty and then everything else looks haggard) there has not been a workman here that has not cursed my dad and was in awe of his work.

Where there was to be six inches of cement there is twelve–all reinforced with wire mesh, never know when a hurricane may blow through. Where it needed two nails there are twenty-two. And the studs—well my father was from the waste-not school. Even single stud, spaced 11 inches apart not the standard 16, was reinforced at the bottom and top with the purple stamped ends of the grape crates that he made wine with. They are everywhere. When I had a closet made bigger, I put one of the crate ends inside the closet along the molding. No one else knows it is there but I know and somehow it is a part of the history of this house and it make me feel happy.

I look at my kitchen now with its 38-inch cabinets and four-inch quartz counters (I am tall), and I am blissfully happy. Oh, I still find stuff to bitch about–but not in my kitchen–it soothes me and makes me glad I didn’t tear out too much hair along the way. Most of it grew back anyway.

Enjoy your new kitchen, David! May you always eat well and drink plenty.

Pieri, I think we may have the same father. My dad built my childhood home, and my parents still live there. Nothing was spared. Reinforced studs, double insulated walls, and no sheet rock–it was hand-applied plaster all the way. When they were pouring the foundation, my parents buried a loaf of bread, a bottle of wine, a dollar bill, and a bible in the walls. The hope was there would always be food, drink, money, and God in its four walls. And that has been the case. It’s 46 years old, and never has the roof leaked, basement flooded, floors warped, or heating failed. I love that house.

My dad even makes his own wine, too. He has a small vineyard in the lot behind theirs. Gotta love those Old World guys.

We are such romantics. We feel a wide swath of emotions. Someone told me once, “it’s good to be able to feel so much”, but, you know what? It hurts a lot, too often.

Stu, never a truer sentiment has been spoken.

No words. What a tribute to friends and memories. Very nicely done.

Thanks, Sarah. The house is that much more special because of all their warm wishes safely hidden there.