Ever stand at your grill and wonder exactly how grilling works? Not just in terms of the pyrotechnics but the thermodynamics and other technical textbook stuff that takes place?

Here to explain all that—minus the boring lectures and annoying homework—is grilling guru and best-selling cookbook author Meathead Goldwyn, who explains exactly how outdoor cooking works in blissfully plainspoken terms.

And even he confesses there’s a little magic mingled with the chemistry, which makes us like him all the more. Following is a mere snapshot of the abundant and articulate information found in his book, Meathead: The Science of Great Barbecue and Grilling and on his site, AmazingRibs.com. —David Leite

What a griller needs to know

You may have thought you left physics and chemistry behind when you left school, but if you want to eat well, you need to understand that cooking–especially grilling–is all about physics and chemistry, with a little magic mixed in. Here are some foundation concepts every outdoor griller needs to know.

What is cooking?

Cooking is the process of changing the chemistry of food, usually by transferring energy in the form of heat to the food long enough so that it achieves the desired flavor, texture, tenderness, juiciness, and appearance.

The three ways heat cooks food

Food gets hot when molecules vibrate so fast that their temperature rises. When cooking outdoors, heat is transferred to food by three methods. Which one you use is crucial. These processes have been described this way:

- Conduction is when your lover’s body is pressed against yours.

- Convection is when your lover blows in your ear.

- Radiation is when you feel the heat of your lover’s body under the covers without touching.

Let’s be a bit more precise:

Conduction

Conduction is when heat is transferred to the food by direct contact with the heat source. Cooking a hot dog in a pan is conduction. Heat from the burner is transferred to the pan whose molecules vibrate, and pass the vibe on to the wiener. As the surface of the meat gets hotter than the interior, the heat transfers to the center through the moisture and fats. That’s also conduction. Grill marks are a good example of conduction. Heat is transferred to the grill grates and the hot metal brands the meat.

Photo: Joshua Resnick

Convection

Convection is when heat is carried to the food by a fluid such as air, water, or oil. Cooking a hot dog in your kitchen oven where it is surrounded by hot air is convection cooking. So is boiling it in water or deep frying it in oil (you really need to try a deep-fried hot dog once).

If you get one side of your grill hot and put the food on the other side, it is cooked by natural convection airflow. Most gas grills cook by convection. A conventional indoor oven uses natural convection airflow to cook, but a “convection oven” has a fan and an extra heat source near the fan and uses forced airflow.

A convection oven cooks 25% to 30% faster. The moving warm air transfers more energy than stagnant warm air. In either case, airflow only cooks the exterior of the meat, the interior of the meat is cooked by conduction as the heat travels through it.

Radiation

Radiation is the transfer of heat by direct exposure to a source of light energy. Put a hot dog on a coat hanger and hold it to the side of a campfire and you are cooking by radiation. This is how most charcoal grills cook.

Radiant heat delivers more energy than convection heat. Let’s say you have two gas grills. On one grill, the two burners on the right side are on full and two burners on the left are turned off. The air temperature on the left side, the indirect heat side, might be 325°F (163°C) as convection flow of air from the right side circulates over the left side. Let’s put a steak and a big honkin’ prime rib roast on the left, indirect side.

On the second grill you have all four burners on medium and the air temp on both sides is also 325°F (163°C). Let’s put a steak and a roast on this grill too. The steak’s bottom will brown better on the second grill because it is above direct radiant heat which is imparting more energy than the first grill where the heat is from convection air. But by the time the roast is done, it will be blacker than a mourning hat.

The distance from the energy source is also an important factor. Energy dissipates as you move away from the heat source. In an $800 grill made of ceramic the heat source may be 2 inches from the cooking surface while on an $89 Weber Kettle the charcoal is only 4 inches away and on a $30 Hibachi the coals may be as little as 1 inch away.

The walls of a ceramic cooker are thick, they absorb huge amounts of heat, and then release it evenly, making a very efficient oven with very steady cooking temps and very low fuel use. Perfect for roasts. But a steak on the cooking surface will not brown as well as on the Weber or even the Hibachi because the coals are so far away and because much of the heat comes from the ceramic side walls and dome, not glowing radiant hot coals right below the meat.

The magic of infrared

If you remember your high school science, you know that infrared is a section of the wavelength continuum around us, just up the road from visible light and down the road from the radio in your car.

Infrared radiation is the best method for delivering high heat to food on a grill. Charcoal grills produce a lot of direct scorching infrared radiation that is converted to heat when it strikes food. Gas grills produce mostly convection heat. Convection heat can be dissipated easily by air currents and distance while IR gets through.

In the past few years, a number of gas grills have been touting their superiority because they use infrared heat or they have an IR sear burner or sizzle zone designed to generate high heat for getting a dark sear on meat. This is an attempt by gas grill manufacturers to close the gap with charcoal grills.

In an IR gas grill a plate of special glass, ceramics, or metal absorbs the heat and light from the flame and re-radiates it to the food in the form of IR.

Photo: TEC Infrared Grills

Is IR heating better? According to AmazingRibs.com science advisor, Dr. Greg Blonder, “IR energy is delivered faster than convection, but slower than conduction. So it can brown a little more effectively than a conventional grill but not as fast as a hot pan or grill grates. There are fewer hot spots from IR cookers. On the other hand, you can get thermal runaway with IR. If one section of the meat is dark, it absorbs more IR than the lighter sections. It browns, becomes darker still, and eventually burns.” And real IR burners are not good at achieving low temperatures.

I recommend gas grills with IR burner sections, especially for getting dark sears on steaks and other meats when the browning of the surface creates thousands of new flavor compounds.

How your grill works

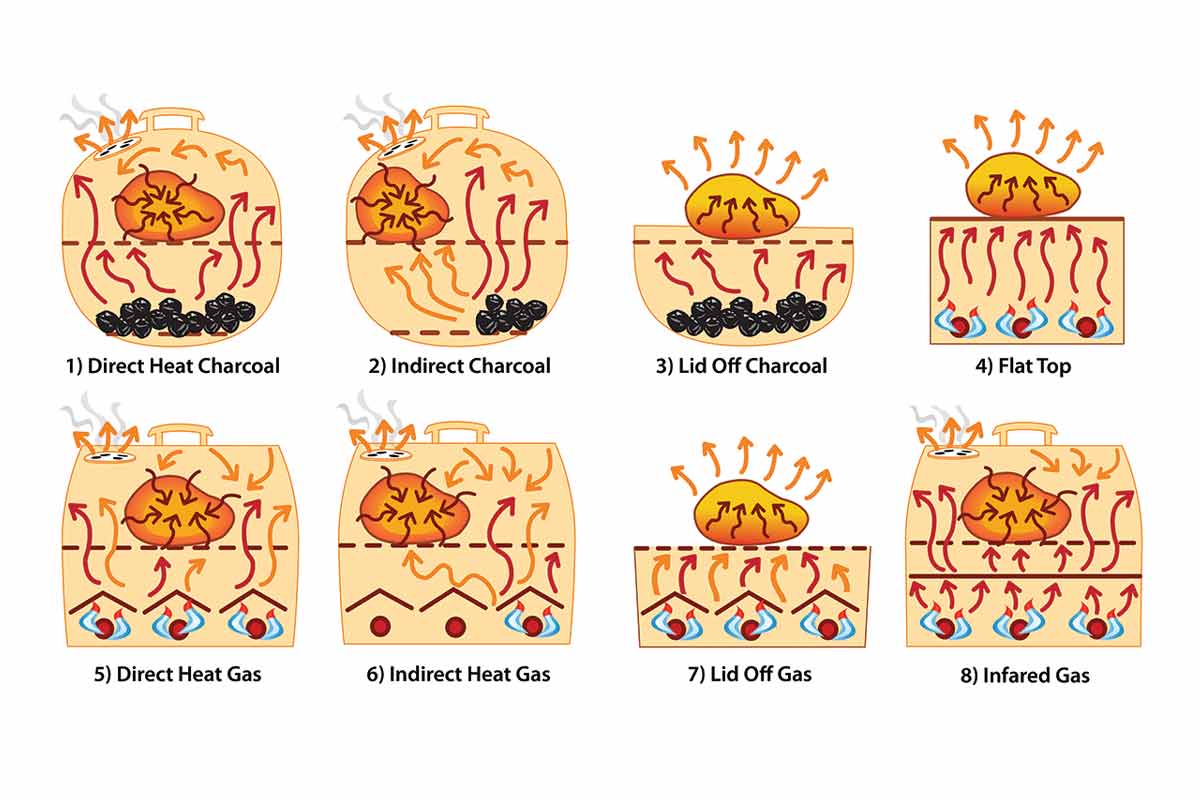

Here’s how different outdoor cookers work:

Direct Heat Charcoal or Wood

Charcoal produces radiant heat in the bottom. The grates absorb heat and produce conduction heat on parts of the surface of the food making grill marks. The lid reflects mostly convection heat. The exterior of the food absorbs direct heat from below, converts it to conduction heat, and it moves to the center of the food.

Indirect Heat Charcoal or Wood

Charcoal off to the side produces both convection and radiant heat. The grates absorb heat and produce conduction heat on surface of the food making grill marks. The exterior of the food absorbs indirect convection heat from all sides, converts it to conduction heat, and it moves to the center of the food.

Lid Off Charcoal or Wood

Charcoal produces radiant heat. The grates absorb heat and produce conduction heat on surface of the food making grill marks. The exterior of the food absorbs radiant heat from below only. The bottom of the food converts the absorbed energy into conduction heat, and it moves to the center of the food. Without a lid, heat escapes from the food upward, cooling its top.

Flat Top

Gas or charcoal grills produce radiant heat in the fire box. Solid griddle under the food absorbs heat and produces conduction heat on surface of the food. The bottom of the food absorbs conduction heat, browns where it is in contact with the surface, and conducts heat towards the top of the food. Without a lid, heat escapes from the food upward, cooling its top.

Direct Heat Gas

Burners produce radiant heat that heats metal drip protector bars, lava rocks, or ceramic briquets. They absorb heat and produce radiant and convection heat. The grates absorb heat and produce conduction heat on surface of the food. The exterior of the food converts all this incoming energy to conduction heat, and it moves to the center of the food.

Indirect Heat Gas

Burners off to the side produce radiant heat that heats metal drip protector bars, lava rocks, or ceramic briquets. They absorb heat and produce radiant and convection heat. The grates absorb heat and produce conduction heat on surface of the food. The exterior of the food absorbs indirect convection from all sides. The exterior of the food converts the energy to conduction heat and it moves to the center of the food.

Lid Off Gas

Burners produce radiant heat that heats metal drip protector bars, lava rocks, or ceramic briquets. They absorb heat and produce radiant and convection heat. The grates absorb heat and produce conduction heat on surface of the food. The exterior of the food converts the energy to conduction heat and it moves towards the top of the food. Without a lid, radiant heat escapes from the food upward, cooling its top.

Infrared Gas

Burners produce radiant heat that in turn heats a special plate. It absorbs heat and emits it as radiant heat in the infrared part of the spectrum. Grates absorb heat and produce conduction heat where they contact the surface of the food. The bottom of the food absorbs the radiant heat and converts it to conduction heat and moves it to the center of the food. The top of the food is heated by indirect convection heat bounced from the lid.

Illustration: Amazingribs.com

How heat moves within meat

When you put food in an enclosed vessel like a grill, smoker, or an oven, the hot air, which has lots of vibrating molecules, transfers some of its energy to the exterior of the meat. The energy in the air excites the molecules on the surface of the meat and then they transfer heat to the molecules inside it and so on, slowly passing the energy towards the center of the meat like a wave of heat. It takes time because meat is about 75% water and water is a good insulator, especially when trapped inside muscle. The heat moves inward because physics dictates the meat seeks equilibrium in an effort to make the temperature the same from edge to edge. So most of the meat is cooked by the meat, not by the air.

Heat also cooks points and corners more because it can attack on multiple fronts. That’s why the brownies and lasagna in the corners are crunchier. And bones heat at a different rate than muscle tissue because they are filled with air or fat, so in most cases they warm more slowly than the rest of the meat.

When you remove the meat from the heat, it continues to seek equilibrium and continues to cook because the heat built up in the outer layers of the meat continues to be passed down towards the center while some is escaping into the air and cooling the exterior. This phenomenon is called carryover cooking.

A thick piece of meat such as a turkey breast might rise as much as 10°F in about 15 minutes after removing it from the grill because of carryover. A thinner piece of meat such as a thick steak might only rise a couple of degrees, and chicken breast may not rise at all. This is important to know because this 5 to 10°F can make the difference between moist turkey and cardboard, a medium-rare steak and a drier medium steak. To compensate, use a good digital thermometer and remove thick cuts of meat about 5°F below your target temperature.

Meat thickness is more important than weight

The temperature of your food moves slowly upward during cooking, but the thickness of the meat is a major factor in how long it takes to get the center to the desired temperature. A thin steak cooks faster than a thick steak. So a 5-inch-thick prime rib that weighs 8 pounds will be done in the same time as a 5-inch-thick prime rib that weighs 12 pounds. Any recipe that says “cook your steak for three minutes per side” without specifying the thickness of the steak is seriously flawed.

When is meat ready to eat?

Food is ready to eat when it is safe and the target temperature is reached. A medium-rare steak is 130° to 135°F (54° to 57°C) in the center regardless of how thick, how much it weighs, or what temperature it is cooked at.

The single best way to tell if it is time to eat is with an accurate digital thermometer. You cannot tell by poking the meat unless you’re a pro who has cooked the same steaks on the same grill for years.

The single thing you can do to improve your cooking is to get a good digital instant-read meat thermometer. The second most important thing you can do is get a good digital oven thermometer.

Photo: VDB Photos

OK, some foods are hard to read with thermometers. You don’t need a thermometer to tell when asparagus is ready, and because of all the bones it is almost impossible to tell when ribs are ready. But for most meats, there is no substitute for knowing precisely what temperature the food is.

Master of the flame and keeper of time

Good cooking is finding the proper combination of heat and time. The higher the heat, the less time needed. Lower the heat, you need more time. But you just can’t set your cooker for Warp 10 on every food. Some demand low and slow.

Your indoor oven has three basic components to control heat and time: A heat source, a thermostat, and a timer. Your outdoor oven, and an oven is exactly what your grill or smoker is, has a heat source, but only a few have a thermostat or a timer. And that’s why cooking outdoors is much more difficult than indoors. Tell that to your significant other (and sleep on the couch).

To make good food outdoors, you need to become master of the flame and keeper of time. Many grills come with a thermometer, but they are usually crap. The thermometer on my gas grill is often off by 50°F (10°C)! You absolutely positively must have a good oven thermometer.

In addition to knowing what temperature your cooker is, you need to know what temperature your meat is. Cooking without a meat thermometer is like driving without a speedometer. You might think you’re under the limit, but try explaining that to the judge. Or your dinner guests.