Jump To

- The origins of the chocolate chip cookies

- What goes into baking the best cookies

- My quest to find the best chocolate chip cookies

- The Warm Rule

- Resting cookie dough 36 hours is the secret

- Testing the dough resting technique

- The bigger the cookie, the better

- The Rule of Thirds

- Couverture chocolate makes all the difference

- Sea salt on top is the finishing touch

The origins of the chocolate chip cookies

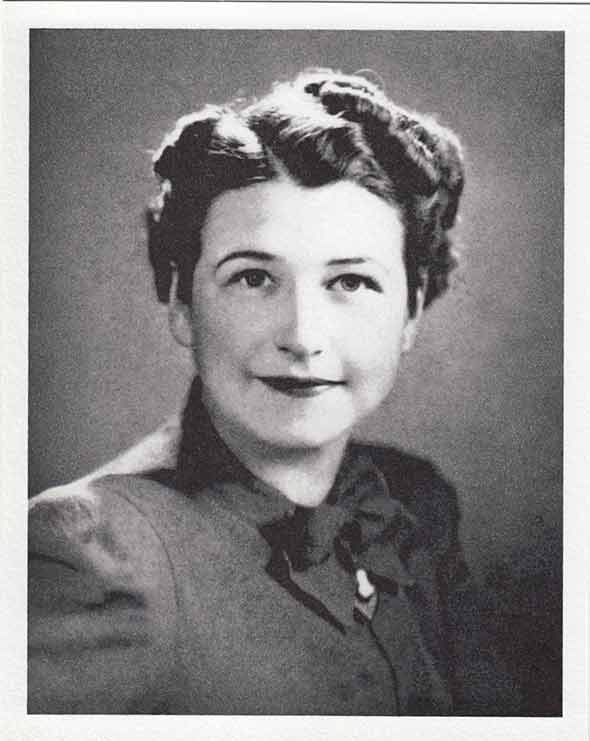

One day in the 1930s, Mrs. Wakefield, an owner of the Toll House Inn, in Whitman, Mass., 23 miles south of Boston, was busy baking in her kitchen.

Depending on which of the many legends you subscribe to, the fateful moment may have happened when a bar of Nestlé semisweet chocolate jittered off a high shelf, fell into an industrial mixer below, and shattered, or when Mrs. Wakefield, in a brilliant move to make her Butter Drop Do cookies a bit sexier, chopped up a bar of chocolate and tossed in the pieces.

Whether by accident or design, her Toll House Chocolate Crunch Cookies delighted her customers and became the mater culinarius, or culinary, mother to an august lineage that almost 80 years later is still multiplying and, in some cases, mutating prolifically.

Made from nothing more than flour, eggs, butter, sugar, leavening agents, salt, and chocolate, the cookie seems idiot-proof. After all, it’s simple enough that an eighth-grader can make it, right?

Not necessarily.

What goes into baking the best cookies

“If it was just a matter of a recipe,” said Hervé Poussot, a baker and an owner of Almondine, in Dumbo, Brooklyn, “we’d all be out of business. It’s what goes into the making of the cookie that makes the difference.”

Like the omelet, which many believe to be the true test of a chef, the humble chocolate chip cookie is the baker’s crucible. So few ingredients, so many possibilities for disaster.

What other explanation can there be for the wan versions and unfortunate misinterpretations that have popped up everywhere—eggless and sugarless renditions; gluten-free chocolate chip cookies, specimens studded with carob, tofu and marijuana; whole-wheat alternatives; and the terribly misguided bacon-topped variety.

All this crossbreeding begs the question: Has anyone trumped Mrs. Wakefield?

To find out, a journey began that included stops at some of New York City’s best bakeries as well as conversations with some doyens of baking. The result was a recipe for a consummate cookie, if you will: one built upon decades of acquired knowledge, experience and secrets; one that, quite frankly, would have Mrs. Wakefield worshipping at its altar.

My quest to find the best chocolate chip cookies

The first visit was to the City Bakery, on West 18th Street, owned by Maury Rubin, who seems to get as much pleasure from talking about food as from eating it. When asked about the secret to his cookies, he said, “We bake them in small batches every hour so they’re always fresh.” He went on to say that the store sells more than 1,000 cookies a day.

Why, then, does almost everybody say they prefer homemade to bakery bought?

The Warm Rule

Mr. Rubin smiled, having already figured out the answer. “It’s the Warm Rule,” he said. “Even a bad cookie straight from the oven has its appeal.”

It’s an opinion expressed by every baker visited. Jacques Torres, who has three branches of his Jacques Torres Chocolate in Manhattan and Brooklyn, has a small warming tray set up near the register so customers can get their cookies soft and gooey, although he offers them at room temperature, too.

Seth Berkowitz, the owner of Insomnia Cookies on East Eighth Street, goes so far as to have a display case filled with baskets spilling over with stand-in cookies; the real deals are sold straight from a holding oven.

Heather Sue Mercer, one of three sisters who own Ruby et Violette, which recently reopened on West 50th Street, believes that her bakery’s basic chocolate chip cookie “is definitely better warm,” but, she said, “I think some of our others are better served room temperature for the best flavor.” A warming oven allows all their cookies to be served either way.

Resting cookie dough 36 hours is the secret

Given the opportunity to riff on his cookie-making strategies, Mr. Rubin revealed two crucial elements home cooks can immediately add to their arsenal of baking tricks. First, he said, he lets the dough rest for 36 hours before baking.

Asked why, he shrugged. “I don’t know,” he said. “They just taste better.”

“Oh, that Maury’s a sly one,” said Shirley O. Corriher, author of CookWise (William Morrow, 1997), a book about science in the kitchen.

“What he’s doing is brilliant. He’s allowing the dough and other ingredients to fully soak up the liquid’—in this case, the eggs’—in order to get a drier and firmer dough, which bakes to a better consistency.”

A long hydration time is important because eggs, unlike, say, water, are gelatinous and slow-moving, she said. Making matters worse, the butter coats the flour, acting, she said, “like border patrol guards,” preventing the liquid from getting through to the dry ingredients.

The extra time in the fridge dispatches that problem. Like the Warm Rule, hydration’—from overnight, in Mr. Poussot’s case, to up to a few days for Mr. Torres’—was a tactic shared by nearly every baker interviewed.

And by Ruth Wakefield, it turns out. “At Toll House, we chill this dough overnight,” she wrote in her “Toll House Cook Book” (Little, Brown, 1953). This crucial bit of information is left out of the version of her recipe that Nestlé printed on the back of its baking bars and, since in 1939, on bags of its chocolate morsels.

Testing the dough resting technique

To put the technique to the test, one batch of the cookie dough recipe given here was allowed to rest in the refrigerator. After 12, 24, and 36 hours, a portion was baked, each time on the same sheet pan, lined with the same nonstick sheet in the same oven at the same temperature.

12 hours

At 12 hours, the dough had become drier and the baked cookies had a pleasant, if not slightly pale, complexion.

24 hours

The 24-hour mark is where things started getting interesting. The cookies browned more evenly and looked like handsomer, more tanned older brothers of the younger batch.

The biggest difference, though, was flavor. The second batch was richer, with more bass notes of caramel and hints of toffee.

36 hours

Going the full distance seemed to have the greatest impact. At 36 hours, the dough was significantly drier than the 12-hour batch; it crumbled a bit when poked but held together well when shaped. These cookies baked up the most evenly and were a deeper shade of brown than their predecessors.

Surprisingly, they had an even richer, more sophisticated taste, with stronger toffee hints and a definite brown sugar presence. At an informal tasting, made up of a panel of self-described chipper fanatics, these mature cookies won, hands down.

The bigger the cookie, the better

The second insight Mr. Rubin offered had to do with size. His cookies are six-inch affairs because he believes that their larger size allows for three distinct textures.

“First there’s the crunchy outside inch or so,” he said. A nibble revealed a crackle to the bite and a distinct flavor of butter and caramel. “Then there’s the center, which is soft.” A bull’s-eye the size of a half-dollar yielded easily.

“But the real magic,” he added, “is the one-and-a-half-inch ring between them where the two textures and all the flavors mix.”

The Rule of Thirds

Testing once again bore out Mr. Rubin’s thesis, which might be called the Rule of Thirds. The 24-hour and, especially, the 36-hour cookies developed the ring Mr. Rubin enthusiastically described.

The crisp edge gave way to a chewy circle, with a flavor similar to penuche fudge, surrounding a center as soft as that of the first batch. His theory on the impact of size on texture so delighted Ms. Corriher that she wanted to include it in her newest book, BakeWise (Scribner, $40).

Super-size cookies seem to be the 21st-century rage. Mr. Torres and Mr. Poussot sell cookies as large as Mr. Rubin’s.

Levain Bakery, on West 74th Street, offers six-ounce, slightly underbaked behemoths that, while not adhering to Mr. Rubin’s Rule of Thirds—they’re too mounded for that—do have some crunch around the edges.

Couverture chocolate makes all the difference

And what would a chocolate chip cookie be without the wallop of good chocolate? According to most of the bakers, only chocolate with at least 60 percent cacao content has the brio to transform the dough into the Hulk Hogan of cookies.

Some, like Mr. Rubin and Mr. Torres, have their chocolate made exclusively for them. Others, including the Mercer sisters, use high-quality imported brands, like Callebaut or Valrhona, and shoot for a ratio of chocolate to dough of no less than 40 to 60.

Break apart a Torres cookie, and a curious thing happens. Inside aren’t chunks of chocolate, but rather thin, dark strata.

“I use a couverture chocolate, because it melts beautifully,” he explained, something traditional chips don’t do. Couverture is a coating chocolate used, for instance, for covering truffles.

To get his trademark layers, Mr. Torres has his chocolate, which is manufactured by the Belgium company Belcolade, made into quarter-size disks’—easily five times the volume of a typical commercial chip. Because the disks are flat and melt superbly, the result, he said, is layers of chocolate and cookie in every bite.

Sea salt on top is the finishing touch

Dorie Greenspan, author of several baking books including Baking: From My Home to Yours (Houghton Mifflin, 2006), was asked to fill in any blanks left by the master bakers during the quest for the ultimate cookie.

Although unsure she could bring anything new to the party, she went through the usual checklist: read through the recipe first, make sure all the ingredients are at room temperature, use the best-quality ingredients you can find, don’t overmix. Then she hit upon something everyone else had missed, and some home bakers are nervous about: salt.

“You can’t underestimate the importance of salt in sweet baked goods,” she said. Salt, in the dough and sprinkled on top, adds dimension that can lift even a plebian cookie.

To make the point, she referred to her recipe for Sablés Korova (Word Peace Cookies), a chocolate chocolate-chip cookie with a hefty pinch of fleur de sel, from her book “Paris Sweets” (Broadway Books, 2002).

Five years ago, sea salt as a must-have ingredient and garnish for sweets wouldn’t have registered on the radar of many home bakers, but now it has become almost commonplace, in part because of Ms. Greenspan’s unwavering belief in its virtue.

After weeks of investigating, testing and retesting, the time had come to assemble a new archetypal cookie recipe, one to suit today’s tastes and to integrate what bakers have learned since that fateful day in Whitman, Mass.

The recipe included here is adapted from Mr. Torres’s classic cookie, but relies on the discoveries and insights of the other bakers and authors. So, in effect, it’s all of theirs’—the consummate chocolate chip cookie.

This creation, the offspring of some of baking’s top talent, truly bests Mrs. Wakefield’s. Doubt it? There’s only one way to find out.

Article © 2008 The New York Times. All rights reserved.

© 2008 Leite’s Culinaria, Inc. All rights reserved.Terms of use.

Do you have a substitute flour(s) for gluten-free chocolate chip cookie recipe? Instead of bread and cake flour? the cookies are to die for..I have not made them but my cousin gave me the recipe and made some..OH MY GOD!! Excellent!

Thank you, Carol! We’re delighted that you love them as much as we do. As for making them gluten-free, I’d recommend that you try this gluten-free chocolate chip cookie recipe, as it is designed to be made with gluten-free flours.

What divine timing. My mother just made the bread for her church community’s Eucharistic celebration tonight. The recipe consists of only unbleached wheat flour and water, and once again, she is lamenting that it baked unevenly: some spots are well-done and relatively flaky, others are decidedly dark and heavy-looking. Next time she’s going to let the dough rest a while and see if it allows more even hydration, and whether that improves the outcome.

Christine, marvelous! please let us know if it works.

Mom tried letting the dough rest for half an hour. Don’t know what it did for the dough but Mom had a good nap. Between one and the other, the results were decidedly better this time. Or maybe she was more diligent in reciting the requisite Psalm 26 while kneading (“Do me justice, O Lord, for I have walked in integrity, and in the Lord I trust without wavering . . .”) Something like Zen cookery, I think. Puts one in the proper disposition.

Ha! Well, I’m glad they turned out. You need to let me tak to Momma Venzon. A half hour?! It needs far longer for any real results. At least she got her nap and prayer in there.