Who really needs 14 bottles of cooking oils?! Apparently, a lot of us, as a recent survey of some of our pantries revealed. Taste aside, there’s another consideration to use as you’re contemplating which one to use for a particular recipe, namely a term known as an oil’s “smoke point.”

How cooking oils are made

Before we can understand the smoke point of an oil, we need to know the composition of an oil. Some of the most common oils are derived from olives, sunflowers, coconuts, peanuts, and avocados. As such, each type of oil naturally has its own unique chemical composition, which makes it react in a distinct way to heat.

Additionally, the manner in which the oil is processed affects its final composition. How the oil is extracted from the ingredients, whether through chemical extraction, expeller or mechanical pressing, or cold-pressing. (Cold-pressing is typically regarded as the most minimally processed approach which retains most of the original characteristics of the oil.) Any further refining of the oil is essentially, a filtering out of some of the organic materials to render the oil relatively colorless and flavorless. These methods and processes are typically indicated on the label.

It’s this final composition of an oil—the sum of much more than just the actual ingredient—that determines its unique smoke point.

What is a smoke point?

The term “smoke point” refers to the temperature at which an oil literally begins to smoke. This is the temperature at which the components in the oil begin to interact with the oxygen around it. The more an oil has been refined, the fewer compounds remain in the oil to react with the heat and, hence, the higher the smoke point. Unrefined oils retain more of the original characteristics of the ingredient that can react with heat and, depending on the oil, sometimes have a lower smoke point than refined oils.

What happens if you go past a smoke point?

Taking an oil past its smoke point—whether intentionally because you love a good sear or by mistake when you get distracted posing for an Instagram selfie—can have several effects. First, obviously, you’ll see wisps of smoke. This is your most reliable indication that the oil is, indeed, too hot—and it’s pretty certain to ensure your smoke alarm will screech.

You’ll also notice that whatever you proceed to cook in that oil—if, that is, you don’t let the skillet cool, wipe out the oil, and start again—will take on an acrid flavor.

And there’s more happening on a stealth molecular level. Some oils contain beneficial nutrients (Omega 3s, we’re looking at you) that are annihilated when overheated. Many health experts agree that overheating an oil (or, if you’re deep-frying, reusing the oil) not only destroys these healthful attributes but can actually release bad juju—including possible carcinogens—into the air and oil.

And, as if that’s not enough, it’s within the realm of possibility that an oil can ignite if it remains above its smoke point long enough.

We’re not trying to instill fear deep in your soul. We’re simply saying that when your oil achieves that beautifully shimmery stage but isn’t quite emitting any wisps of smoke, you’ve nearly reached the smoke point. That’s when it’s time to stop dallying and cook—and not crank the heat any higher. And if, by chance, the oil does start to smoke, we advise you to turn the heat off, let the pan cool, wipe it out thoroughly, and try, try again.

What are the smoke points of different oils?

It gets a little complicated when it comes to delineating smoke points. Because olive oil isn’t always just olive oil. If you recall what we explained above about oil being refined, unrefined, raw, virgin, or extra virgin, or, you know, processed under the light of a full moon during Mercury retrograde, there’s a lot that needs to be taken into consideration.

This means that refined “light” olive oil may be great for sautéing over a decent flame while an unrefined extra-virgin olive oil is far too delicate to be exposed to that kind of heat.

Furthermore, different research studies conducted on even oils derived from the same ingredient invariably draw on slightly different iterations of the same oil. Even unrefined avocado oil can vary somewhat from brand to brand, resulting in different purported smoke points for the “same” avocado oil.

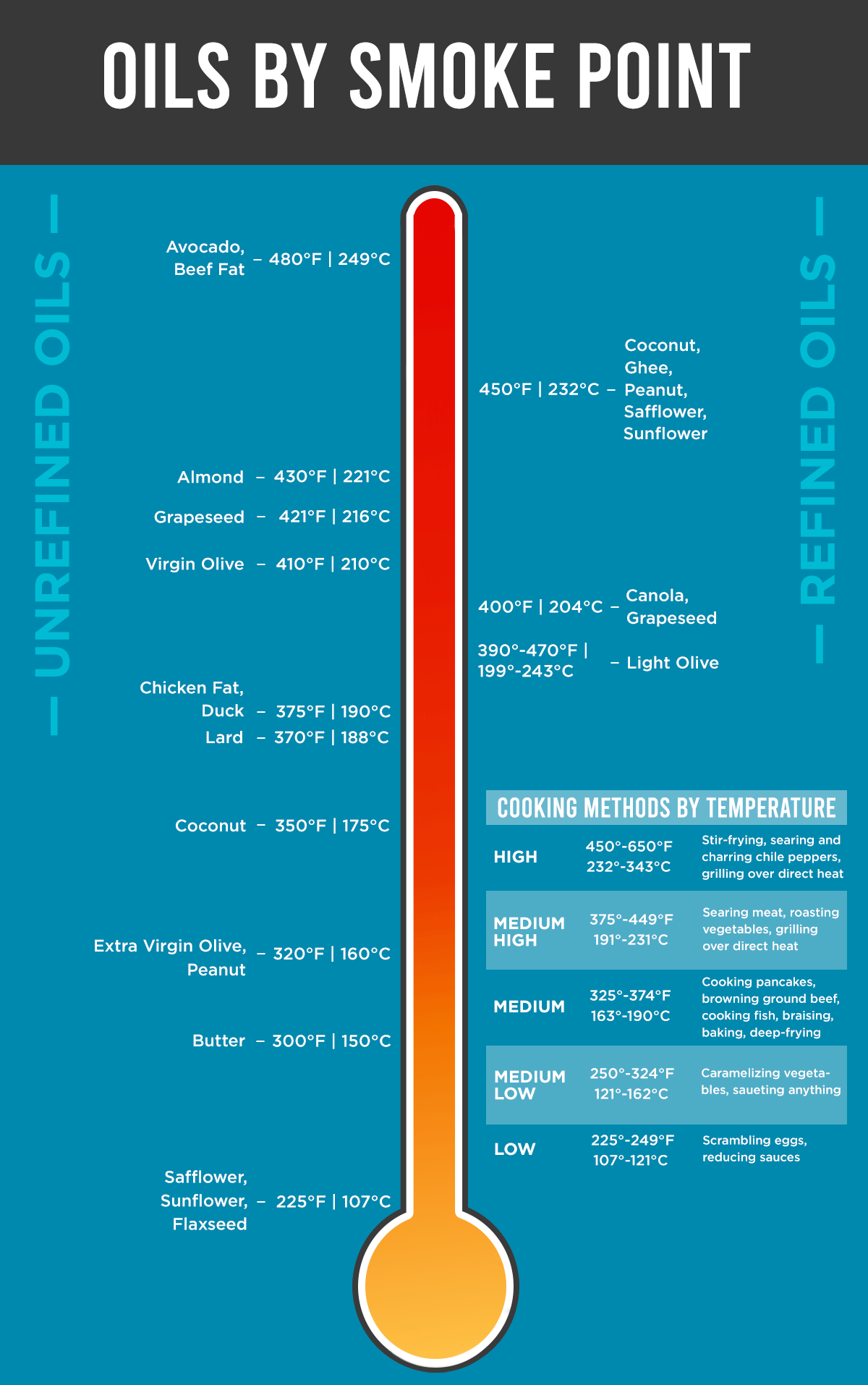

Below is a cheat sheet we’ve compiled on smoke points. We’ve based it on the most reliable research we could find and erred on the side of caution when we encountered a range of temperatures for the same type of oil, opting for the lower end of the reported temperature. But because of the variance in oils, as explained above, actual smoke points may vary slightly from what you see below. But it’s a solid guideline.

So watch for that lovely shimmer. And let’s be careful out there.

Chat with us

I would take this smoke point image down immediately and instead put up a correct one. You have Safflower and Sunflower way at the bottom with the listed Fahrenheit as what their actual Celsius smoke temp is. They smoke at 225C° not F. Whoever checks your facts needs a new job

Thanks for your comment, Robert. If you look at the graphic, you’ll see that the smoke points listed on the left are for unrefined oils, while the ones on the right are for refined oils. Refined oils have a high smoke point, as you’ve referenced, so you’ll find the refined sunflower and safflower oils listed high on the thermometer on that side of the graphic. Unrefined oils have significantly lower smoke points, which is what you are seeing on the left side of the graphic.

Why is coconut oil listed twice?

Jim, you can buy refined or unrefined coconut oil and their smoke points differ, which is why it’s listed twice in the chart.