The problem wasn’t just that August night. This time last year, things weren’t going well. Work was scarce, household finances unstable. But even money woes seemed preferable when set against my emotional state. Drained and depressed, I’d sunk into a lingering malaise. Maybe it was the realization that I was turning 40. Maybe the role of Restaurant Widow was taking its toll: I almost never saw my husband, a sommelier. Come Sundays, we were too exhausted to connect or even care that we didn’t. Plowing through the weeks with something akin to single-parent status, I sat alone most nights feeling irrelevant and irritable, full of too many thoughts and too much hunger.

Searching for comfort, I immersed myself in the desserts section of the book. A simple spice cake caught my eye. The ingredient list was nothing much—it included the walnuts, cinnamon, and cloves typical of Greek pastry—but the name of the recipe intrigued me, as did its legend.

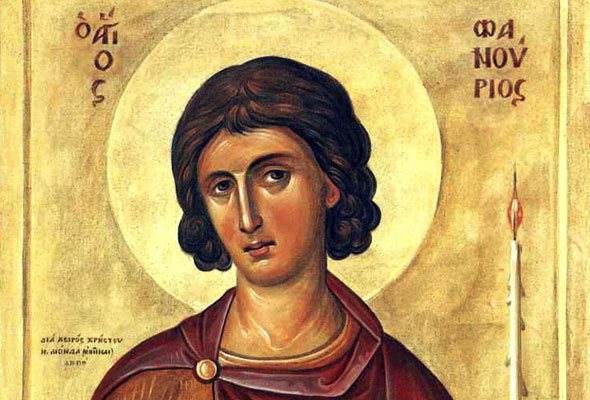

Called a phanouropita (pronounced “fan-oo-RO-pee-ta”), the cake honors the Greek Orthodox Saint Phanourios, a martyred soldier whose icon, lost for centuries, was found in perfect condition under the rubble of a ransacked church in Rhodes in the early 1500s. Since then, worshippers, mostly women, have followed a tradition of baking and giving away this cake when they want to locate something missing. Phanourios, whose name relates to the Greek verb “I reveal,” apparently will find things for you, but you have to ask him. Sweetly.

Phanourios appealed to me. In his icon, he holds a lit candle, the promise of revelation, and I was sick of sitting in the dark. In truth, I felt lost. Maybe this saint and his cake could help.

According to the recipe I used that day, custom required beating the batter with a wooden spoon for nine full minutes. (Nine, I found out later, are the levels of holy angels in the Church.) After two or three minutes, I was losing enthusiasm. At six minutes I started equating the task with penance. By the nine-minute mark, I figured I’d atoned for a lifetime of sin but found myself in hell anyway. My arm was on fire.

The batter had a strange consistency, gummy and dense. I coaxed it to the corners of a loaf pan. I figured it was a flop but couldn’t know unless I baked it. First, however, some ceremony was in order. I placed a printout of Phanourios’s icon on the counter and searched my mind for something the saint could retrieve for me. My husband wasn’t exactly missing; I hadn’t lost my keys or wallet. I could use another paying job, but that seemed too ambitious to start with.

In the end, I failed to ask for anything. I did, however, crouch in front of the oven to make a timid sign of the cross. When my son wandered into the kitchen and asked what I was doing, I quickly straightened and stuffed my hands in my pockets. “Nothing,” I said. “Baking a cake.”

The cake smelled like something from my grandmother’s kitchen. Cutting the traditional nine slices (those angels again), I ate one to be sure it tasted good, then bagged the others. On Sunday I planned to visit Manhattan’s Greek Orthodox Cathedral, where I’d never been before. I had no idea who I’d give the cake to, but it turned out not to matter—encountering a man begging in front of the church (he almost seemed planted there to test me), I realized I’d forgotten to bring the cake along. I gave him a dollar, sat through three hours of service, and went home. I did venture out with the cake later on, but gave up after the first homeless person turned it down.

Even giving the cake away was harder than I’d imagined.

I’m not sure what compelled me to make a full-blown project out of the phanouropita, why I couldn’t just let it go. Maybe it was stubbornness. More likely, I harbored some masochistic hope that if I kept pressing the sore, hollow spot I felt—if I kept making the cake—eventually I’d discover what was missing. I gave away cake after cake, sometimes leaving them next to sleeping homeless people, other times donating them to the church or giving them to friends. I tried different recipes and meditated on more specific prayers: perhaps the saint could find me a new client after all, or a magazine willing to take a story. I started keeping score: cakes baked, prayers answered. I prepared the same recipe in a purgatorial loop, sifting and mixing week after week, waiting for something to happen.

While I waited, I decided to take classes in food writing and offered my services as a recipe tester. I began developing and sharing my own recipes as well, wading slowly into the blogging community. I got to know the owners of Greek bakeries and specialty shops, and wherever I encountered Greeks, I made sure to ask about the cake, unearthing anecdotes about the mysterious saint. I found women who swore that Phanourios had found them a husband, or health, or a tenant for an empty apartment. Salt cellars appeared, as did wayward legal documents. The secondhand testimonials were inspiring and only intensified my craving for an outcome I could call my own.

During the first weeks of 2010, the scorecard for Phanourios stood at 11–0. I’d baked 11 cakes and none of my prayers had been answered.

Sure, the repeated act of baking and giving away a modest cake had brought me a keener sense of purpose. Yes, its traditions shoved me out into the world again, where I was interacting with people who shared my interests, especially food. And it was true that I wasn’t exactly alone anymore, rattling around inside a disconnected life. I’d found—or had been shown—new ways of engaging with others, ways that went beyond the confines I had assumed were inevitable for a stay-at-home mom, a home-alone wife, and a freelance professional whose desk was the dining table and who worked, next to piles of wrinkled laundry, on assignments for clients I never saw.

Suddenly I was stunned by my lack of insight. I’d been waiting for something that hadn’t arrived. Yet the saint had delivered the one thing I’d been missing most of all: connection. He’d done this even when I didn’t know to ask for it by name.

As for the things I did request, from that moment, they started coming, too, fast and furious through the rest of the year. New clients in the city, lucrative projects, recipe contests, and publication—Phanourios and I went on a tear. I began to think of this mysterious martyr, this solider with a sweet tooth, as my patron saint. I continued to haul his cakes around town, making them for charity events and giving them to strangers down on their luck. But the quid pro quo was over, and I stopped keeping score. There was no need to think about it anymore. Baking the cakes was now just something I did, often on Sundays—something that fed my spirit at the end of a rewarding week’s work.

There’s a deliciousness to my days now that wasn’t there before, a gratitude for the many ways I now connect with others and make a more significant contribution to the world around me. I bake the cakes less frequently, that’s true. Writing, recipe development, family life, and a full client load take up most of my time. Tomorrow, though, August 27, is the feast day of Saint Phanourios. Tonight I will bake the twenty-sixth cake in his honor. I’ll sift powdered sugar gently over the top, slice it, and have some in the morning with coffee. When I do, I’ll say a grace for all the ways my life has changed in the past year. As for giving the cake away, with my recipe for phanouropita—and a sense of what’s possible—I give it to you.

Allison, I am a pretty regular reader of Leite’s Culinaria, but I missed your essay when it was originally published. I just discovered it through Saveur’s Best finalists. (Congratulations on making that list, by the way!) I really love this essay….it speaks to me on many levels. I’m off to vote for you. Phanourios has found you another fan!

Kath, thank you so very much. I am glad that the essay speaks to you, and I really appreciate your taking the time to let me know. I’ve no doubt that this saint is still working on my behalf!

Dear Allison,

Happy New Year and I hope your holidays were great. I never got your email, but i did get your final comment that you left me on here. Please use the email attached to reach me. I still am insterested in having a conversation with you when you can. I would like to share with you a story, how a couple I know from sharing this experience and recipe has been making this cake once and sometimes twice a month and conitnue this act of prayer and offering since August. I hope to hear from you soon. With prayers and Best Wishes.

Fr. Ignatios

Thank you, Father Ignatios, and to you as well. I’m sorry my message didn’t reach you. I’ll try again as you suggest. I would love to hear all about the couple who has been continuing to bake the phanouropita regularly!

Allison, I stumbled upon the link to your article quite by chance, reading through some old discussions on “She Writes” forum. And I am so happy that I followed it. You are a wonderful writer and for a moment I was sitting right next to you, depressed and lethargic, throwing all the emptiness away in nine minutes of kneading (I bet it was my Njanja who wrote that recipe!)

I love the symbolism of your story. (I am traditionally Serbian Orthodox, and even though I do not know this particular saint, I am familiar with many others:) and admire “the character arch” you accomplished in such a short time, with St. Phanourious or without ( I have my own little idiosyncrasies similar to yours).

I read LC pretty regularly, but finding your voice on the site is going to make me come back daily. Thank you!

Lana, for some reason I can’t fathom, I am only seeing your comment now. So sorry. I wanted to tell you that I really appreciate your taking the time to leave a comment here. Your words mean a lot to me–if I could bring you on a journey with me, it’s the best part about being a writer. I smile to think that you found such recognition in the scene of perpetual mixing that it made you wonder whether your own “njanja” could have written the recipe! Anyway, I hope that you have indeed come back to Leite’s often in the time since you left your comment—and that you’ve found much to delight your senses (especially that of taste!) here. Thanks again.