Remember those cartoons with a classic apple pie cooling on a windowsill, a billowy cloud wafting from it? The aroma would unfailingly hook an unsuspecting character by the nose and draw him like a ragdoll to its sweet, sweet source. I’m pretty sure that’s what I looked like the first time I caught the scent of Belgian waffles.

It was seven years ago. I’d just moved to Brussels and was eager to explore my new surrounds. I’d set out for the weekly farmers market near my house, and it was there that the scent cloud first tickled my nose. Like a dog with a nervous tick, I twitched my head side to side, sniffing the wind until I found the source of honeyed air. It was a large white and yellow truck the size of a well-equipped motor home and kitted out as a mobile patisserie. One side of the truck was hinged and propped up to form an overhead shelter that protected a glass display case above the wheel wells. Within were delicate pastries and cookies—gems in a jewel case.

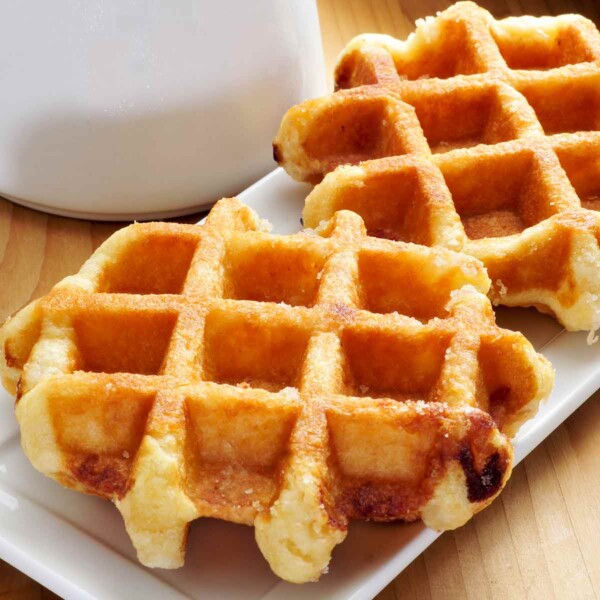

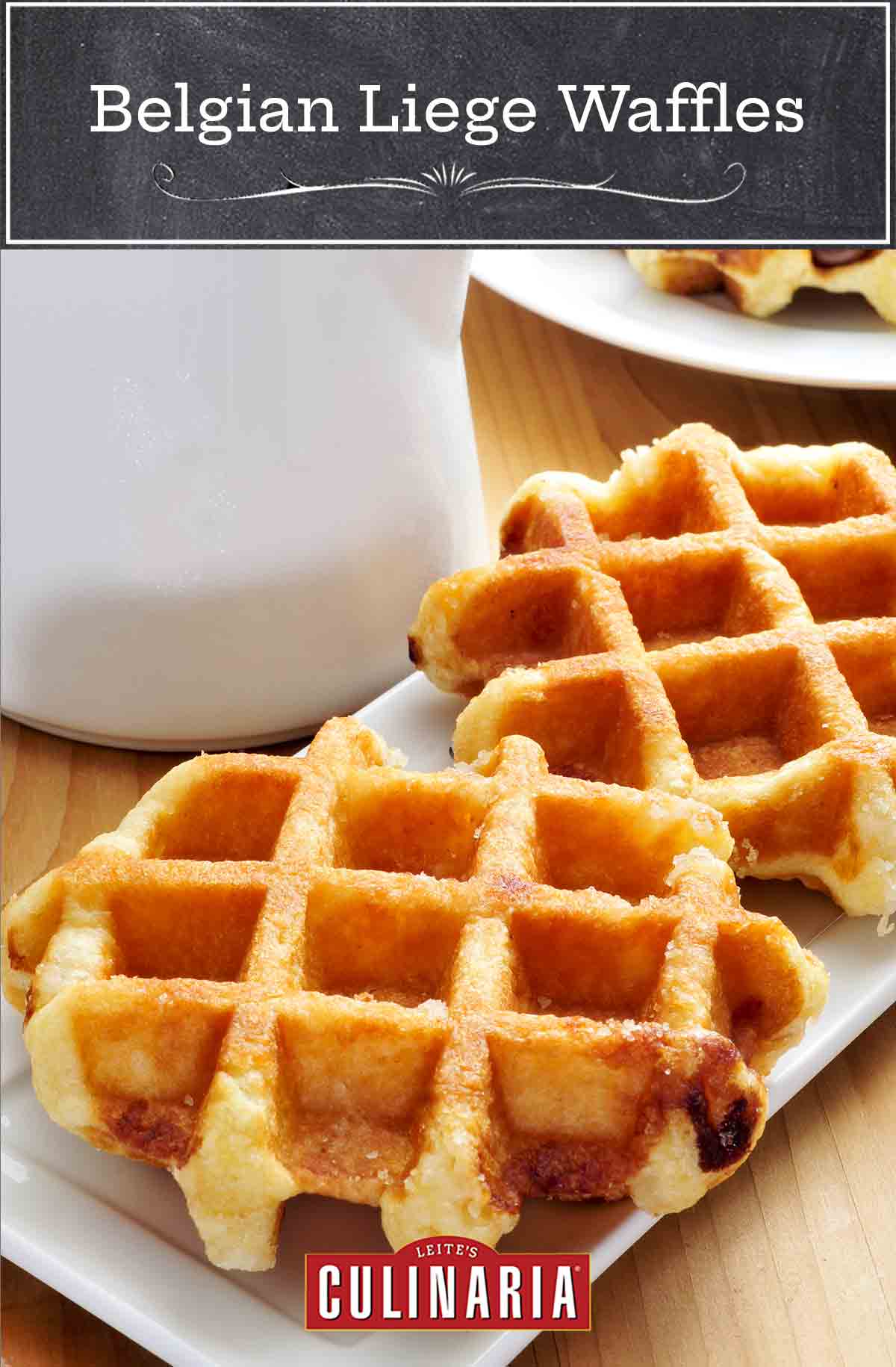

But I was ogling something else. Off to the side, near a stack of baguettes, a waffle iron sat, steaming and puffing, oozing crusted batter drippings. Without hesitation, and pointing dumbly to the billowing iron in hopes of relieving any doubt as to exactly what I wanted, I said, “Une gaufre, s’il vous plaît.” A waffle, please. A man—Gilles, I would later learn, thanks to my biweekly visits—took a utensil resembling a barbecue fork and peeled the crenellated confection off the knobs of the iron, folded a piece of wax paper around it, and handed it over. I cradled it in two hands as if it were a piece of fragile glass. This waffle was nothing like the IHOP version of a “Belgian” waffle I’d grown accustomed to in the U.S. In my hand was a warm, ginger-brown oblong waffle about the size of a kitchen sponge. With no maple syrup and no whipped cream smiley faces in sight, I sunk my teeth into the dense, sweet, chewy confection known as a Liège (pronounced LEE-ezh) waffle. The caramelized crust gave way easily and the taste of butter and sugar melted on my tongue. It was love. My understanding of a true Belgian waffle—and my waistline—would never be the same. The Belgian waffle as we know it in America actually originated as the “Bel Gem Waffle,” a food created by Belgian restaurateur Maurice Vermersch for New York’s 1964 World’s Fair. Waffles became a national craze in subsequent years, the waffle iron a fixture in American kitchens. The name “Bel Gem” mutated first to “Belgium,” then to “Belgian,” forever linking the flat country to maple syrup-splattered diner menus across the 50 states.

Belgium isn’t totally blameless here—the small quiet types never are. Though Vermersch’s rendition was a far cry from the waffle nirvana I’d experienced at the market, it was actually patterned after a “Brussels” waffle. This is a cousin to the authentic Belgian waffle yet more closely resembles the American version. Leavened with yeast and egg whites, it’s fluffier than the real Belgian deal and served in a stack throughout its namesake city, with toppings such as chocolate sauce, whipped cream, and strawberries.

Want to Save This?

However, the most common type of waffle in Belgium, and in my opinion the most bewitching, is the doughy diva I discovered that day in the market. Named for a town in southeast Belgium, the Liège waffle is cooked on an extremely hot iron that caramelizes the chunks of pearl sugar in the batter, creating a glistening crust that enrobes the buttery, vanilla-y cake beneath. It’s eaten by hand in Belgium—and never for breakfast—though I’ve been known to eat them morning, noon, and night. Street vendors around Brussels prepare and serve them hot off the iron from vans parked at just about every market and main shopping area. I’m partial to the vans in front of the city’s most beautiful landmarks and vistas.

You really don’t need an excuse to indulge in a Liège waffle—at least I certainly don’t. But August 24 marks the anniversary of the first U.S. patent for a waffle iron. It’s not the same as the iron used for an authentic gaufre Liège, yet it’ll suffice. Well worth the effort, this recipe is somewhat more sophisticated to make than a toaster waffle yet slightly less difficult to produce than a tiered wedding cake. If you can’t bring yourself to make it from scratch, don’t worry. Chances are there’ll soon be a waffle truck near you. You’ll know it when you smell it. Just follow that billowing scent cloud.–Kimberley Lovato

Liège Waffles

Ingredients

- 1 1/2 teaspoons active dry yeast

- 1/4 cup scalded whole milk*, [110°F to 115°F (43°C to 46°C)]

- 2 tablespoons plus 2 teaspoons warm water, [110°F to 115°F (43°C to 46°C)]

- 2 cups bread flour, plus more for dusting

- 1 large egg, room temperature, lightly beaten

- 1 tablespoon plus 1 teaspoon light brown sugar

- 3/4 teaspoon salt

- 8 1/2 tablespoons (4 1/4 oz) unsalted butter, room temperature

- 1 tablespoon honey

- 2 teaspoons vanilla extract

- 3/4 cup Belgian pearl sugar, (Lars Own brand is an excellent choice) or sugar cubes that you’ve coarsely crushed in a mini chop or a food processor

Instructions

- Dump the yeast, milk, and water in the bowl of a stand mixer and combine until the yeast is just moistened. This ought to take but a few seconds. Add the egg and 2/3 cup of the flour and mix just until incorporated. Sprinkle with the remaining flour but do not stir. Cover and let stand until the batter is bubbling up through its mantle of flour, 75 to 90 minutes.

- With the mixer on low speed, add the brown sugar and salt to the batter and mix just until combined. With the machine still running, add the honey and vanilla and mix until combined. Add the butter, 2 tablespoons at a time, and mix for 4 minutes on medium-low speed, scraping down the sides of the bowl once or twice during that period. Let the dough rest for 1 minute and then continue to mix for 2 more minutes. (The dough should be sticking to the sides of the bowl during the last minute of mixing and then, in the last 30 seconds or so, it should start to ball-up on the paddle. If this doesn’t happen, let the dough rest for 1 more minute and mix for another 2 minutes. Whatever the outcome of the extra mixing, proceed to the next step.)

- Turn the dough into a large bowl and sprinkle very lightly with flour. Cover with plastic wrap and let rise at room temperature for 4 hours.

- Now cover and refrigerate the dough for 30 minutes.

- Stir the dough down by pressing on it gently to deflate it. Carefully scrape the dough onto a piece of plastic wrap and then press the dough into a long rectangle. Fold that rectangle over onto itself in thirds, like a letter, so that you have a square of dough. Wrap it in plastic, weigh it down a bit (I place two heavy dinner plates on top of it), and refrigerate overnight.

- The next day, place the cold dough (it’ll be quite firm) in a large bowl and add all of the pearl sugar to the bowl. It will seem like a lot of sugar, but it’s supposed to be a lot. Mix the sugar into the dough by hand until the chunks are well distributed. Once mixed, divide the dough into 5 pieces of equal size. Shape each chunk into an oval ball (like a football but without the pointy ends) and let it rise, covered loosely in plastic wrap, for exactly 90 minutes.

- If you have a professional waffle iron (meaning it’s made from cast iron and weighs over 20 pounds) cook at exactly 365° to 370° F (185° to 187°C) (the max temp before sugar begins to burn) for about 2 minutes. If you have a regular waffle iron, heat the iron to 375° F (190°C) and cook for 4 to 5 minutes. (Many regular waffle irons go up to and over 550° F (287°C) at their highest setting. I suggest you place the dough on the iron and immediately unplug it or turn the temp dial all the way down; otherwise, the sugar will burn.)

- Let the waffles cool a few minutes before eating, wrapped in waxed paper, if desired.

Notes

*What is scalded milk?

Older recipes often call for scalded milk but it’s not something you see as much anymore. This is a holdover from when milk wasn’t universally pasteurized. So that biscuit recipe passed down from your great-aunt Annie might not need the scalding step for health reasons, anymore. At its most basic, scalding just means bringing milk to a temperature of 180°F and then letting it cool to 110°F (43°C). In the before-times, this helped to kill bacteria and an enzyme that prevented thickening in recipes. But now that milk is pasteurized, why do you need to bother? Scalding still serves a purpose when you add yeast, melt butter, or want to infuse flavor. Scalded milk also has a distinctly different flavor from plain old room temperature milk.

An LC Original

View More Original RecipesExplore More with AI

Nutrition

Nutrition information is automatically calculated, so should only be used as an approximation.

Recipe Testers’ Reviews

This is the best Liège waffle recipe I’ve tried. The waffle comes out sweet with a buttery, malty, yeasty flavor, but not overly yeasty. The outside is crisp and sugary, but there’s a good chew to the interior, along with occasional crunchy sugar-filled bites.

Be forewarned that there’s a lot of non-active time with the recipe; this allows the flavors and texture to develop in the dough. I used pearl sugar but also tried it with sugar cubes crumbled in the food processor. Pearl sugar is best, but I wouldn’t turn down a waffle made with sugar cubes, either. The directions say to mix the sugar in by hand, but I found it easier to knead the sugar into the dough.

I let my waffle iron heat up to 3/4 of the max heat setting and then measured the temperature with an infrared thermometer. I placed the dough oval in the middle and at 370°F, the waffles cooked in two minutes. It seems like a lot of work for five waffles, but they’re rich and easily split into quarters for sharing. All the sugar and butter in the dough left a mess in my waffle iron, but a pastry brush and warm water (on the still-warm iron) cleaned it up.

You need quite a bit of lead time for several rounds of proofing, including overnight refrigeration, for this Belgian Liege waffles recipe. But all of the work and time are worth it when you get five absolutely beautiful waffles that are more like pieces of fine pastry than what we Americans typically call “waffles.”

I used a regular waffle iron and was able to get it to a temperature of 360°F. The dough balls took five minutes to cook–the iron was hot enough to create a beautifully caramelized sugar crust on the outside while cooking the waffle inside to a lovely “brioche-like” texture. I didn’t have pearl sugar so I made my own by crushing sugar cubes with a meat mallet. My only complaint would be that some of the sugar melted and stuck to the waffle iron, making clean-up rather challenging. Perhaps by using actual sugar pearls, this would be less of an issue.

Rick. Hi! So glad you are enjoying these waffles. Sure wish I had a warm batch of my own right now. Yes! Crunches of pearl sugar in the waffle are normal and part of the delicious surprise of biting into a liège waffle. As for your previous question about why the dough must rest overnight–you have me scratching my head. Good question. It must certainly have to do with the yeast and chemistry, letting the right reaction occur to achieve the desired texture, but frankly I am not sure why it has to be an overnight versus a four-hour waiting period. I can’t answer specifically, but have put out the waffle feelers to some “experts” who might know. Have you tried letting the dough sit for a shorter time? If so, were the results any different? Thanks for being so waffle-curious.

Hi Renee – thanks for that! Could you also perhaps ask about the presence of of the pearl sugar? What I mean is that…I get a good caramel on the outside…but there SHOULD be some kinda unmelted chunks in each waffle to be crunched into correct? Thanks!

You’re quite welcome, Rick. I know for a fact that yes, there should be some chunks of kinda unmelted pearl sugar in each waffle to be crunched into. Will get back to you on your other curiosities stat….

Hello, I made these waffles and I did like them…just some questions though, because this recipe is so different to other recipes Ive tried. First, on the last 90 min proving, I found the dough had a “beery, kinda fermented” aroma. Is this normal? After I cooked the waffles ( I used a Cuisinart a on 4.5 and pressed down a little for the 2min cook time), they came out looking wonderful and had a good result from the pearl sugar – but still, that slightly alcoholic taste ( I just want to know if this is common,) Cheers

Hi Rick, I spoke with Leanne and Linda our testers who made the waffles. Leanne said the waffles do have a malty, yeasty aroma in the dough from all the yeast, but there shouldn’t be a fermented aroma. And the cooked waffles definitely should not taste alcoholic after cooking. She wondered if the type of yeast may be the culprit. Linda suggested that you could try increasing the vanilla by an additional tsp or by adding a second complementary flavor, such as orange flower water or a little bit of almond extract, if you found the malty flavor not to your liking.

Hi there- thanks for the reply. Yeah I don’t mind the malty flavor, but I was just wondering if a beery taste was supposed to be prevalent. Personally I don’t think I measured the ingredients correctly. As for the yeast, I used a dried active yeast–everything seemed to be working fine, but it was just the last 90-minute proof that I’m wondering about. Also, could you tell me what exactly the overnight refrigeration accomplishes? I’m an amateur baker and I’m not experienced in how this all works, so was wondering if it improves the flavor? Is is just as good to perhaps leave the dough in the fridge for a shorter amount of time, say, an hour or two? Is the process made faster in the freezer instead? Sorry for all the questions–but at the moment I’m very invested and interested in Liege waffle creation. 🙂 Cheers!

Rick, I’ve forwarded your queries along to our most experienced Liege waffle makers and I expect a response any time….

Rick, I see you’ve gotten some answers as well as had some success. Wonderful.

For the record, yeast dough (also called a fermented dough) can have a fermented/alcohol flavor if it rests to long, called over proofing. So my guess is twofold: not properly measuring the ingredients–so you may not have had the optimal ratio of yeast, carbohydrates, and sugar–as well as over proofing.

Hello, David. Yes, overproofing coupled with the definite possibilty of too much sugar/honey I think contributed to the cause of the fermentation. As such, I have not had an issue since I tweaked a couple of things.