This post was updated on Jan 6, 2025, to include more answers to questions and technique info.

Jump To

Captain Ahab had the great white whale. I have the pastel de nata–the famous Portuguese egg tart. This little pastry has dogged me for years, taunting me, daring me to figure out its secret.

My quest started when I reported about them for the Los Angeles Times more than 20 years ago. Since then, I even visited the Antiga Confeitaria de Belém—three times!—where pasteis de Belem been sold since 1837.

The recipe has been a close-guarded secret for 187 years! Only six people know it, and they all meet behind locked doors to make both the custard and pastry dough. (Yes, they’re serious about their pasteis, my friend.) No matter what, I couldn’t get into that room.

Still, as I skulked around the confeitaria’s kitchens, I picked up some clues: the consistency of the uncooked custard, the texture and stretch of the pastry dough, the technique for making the pastry shells. (It’s all in the thumbs.)

All those clues and observations have been added to this recipe over the years. And it seems to have helped! It’s been shared on social media more than 65,000 times and has been mimicked (*cough* “ripped off”) by just about as many food bloggers. And I have it on good authority that a certain British judge on a certain British baking show used my recipe as the basis for a baking challenge. (I can’t hide it; I’m wicked flattered!)

Still, I’m working diligently, tweaking this recipe so that it comes as close as possible to the original.

So, dear Reader, meet the Queen of all Portuguese Pastries. My Queen, meet Dear Reader. My work here is done!

Chow,

Read: The History of the Pastel de Nata

Why This Recipe Works

This custard tart recipe works for several reasons. First, size matters. In Belem, the tarts are large, and the ovens blast at blistering-hot 800°F (400°C). By making the tarts smaller, they bake perfectly in a home oven. Then there’s the sugar syrup. Cooking the syrup to the precise temperature of 220°F (104°C) ensures the custard sets perfectly. Last, the folding and rolling of the dough gives you that shatteringly crisp spiral of countless layers.

What’s a Pastel de Nata?

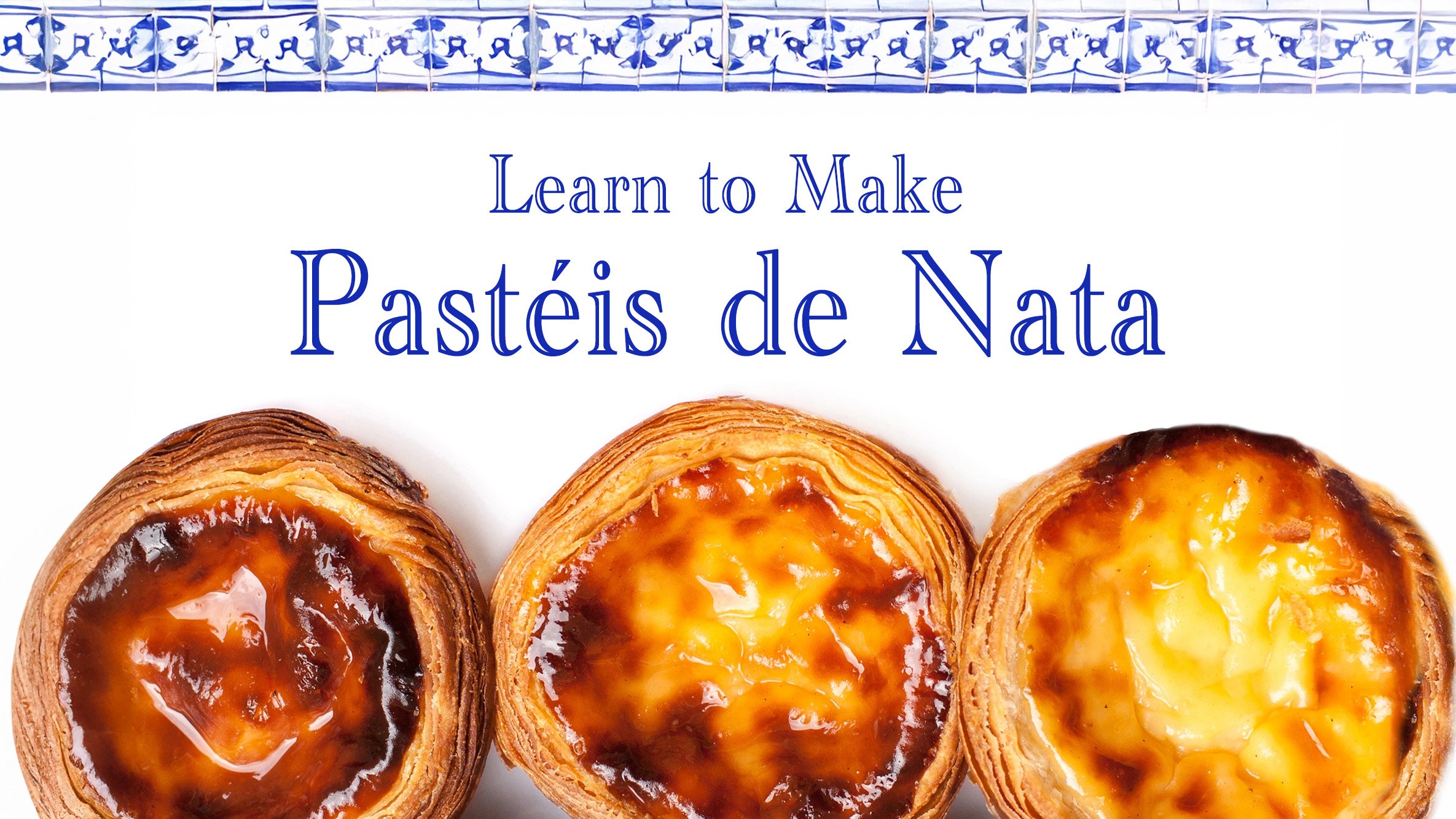

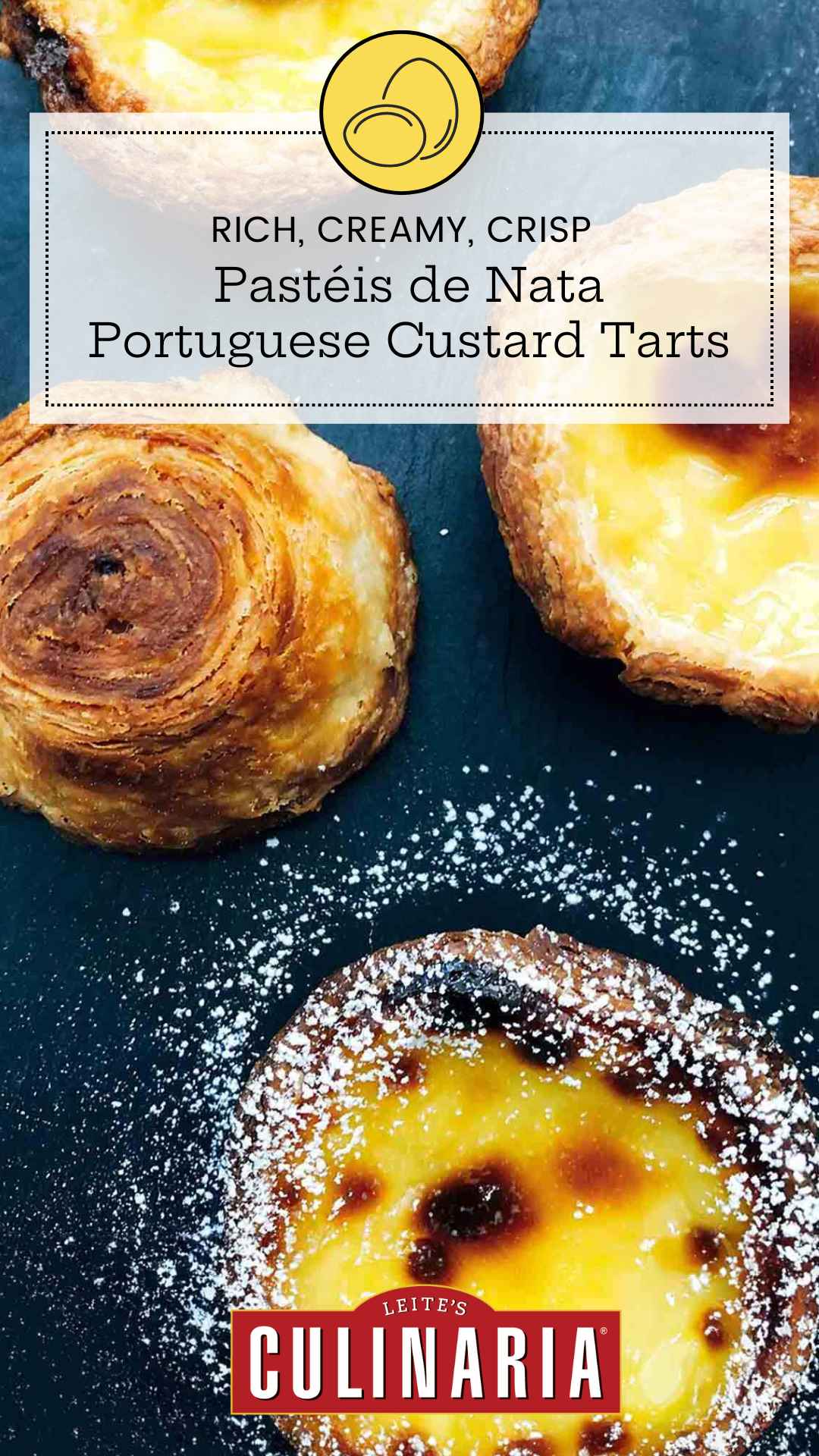

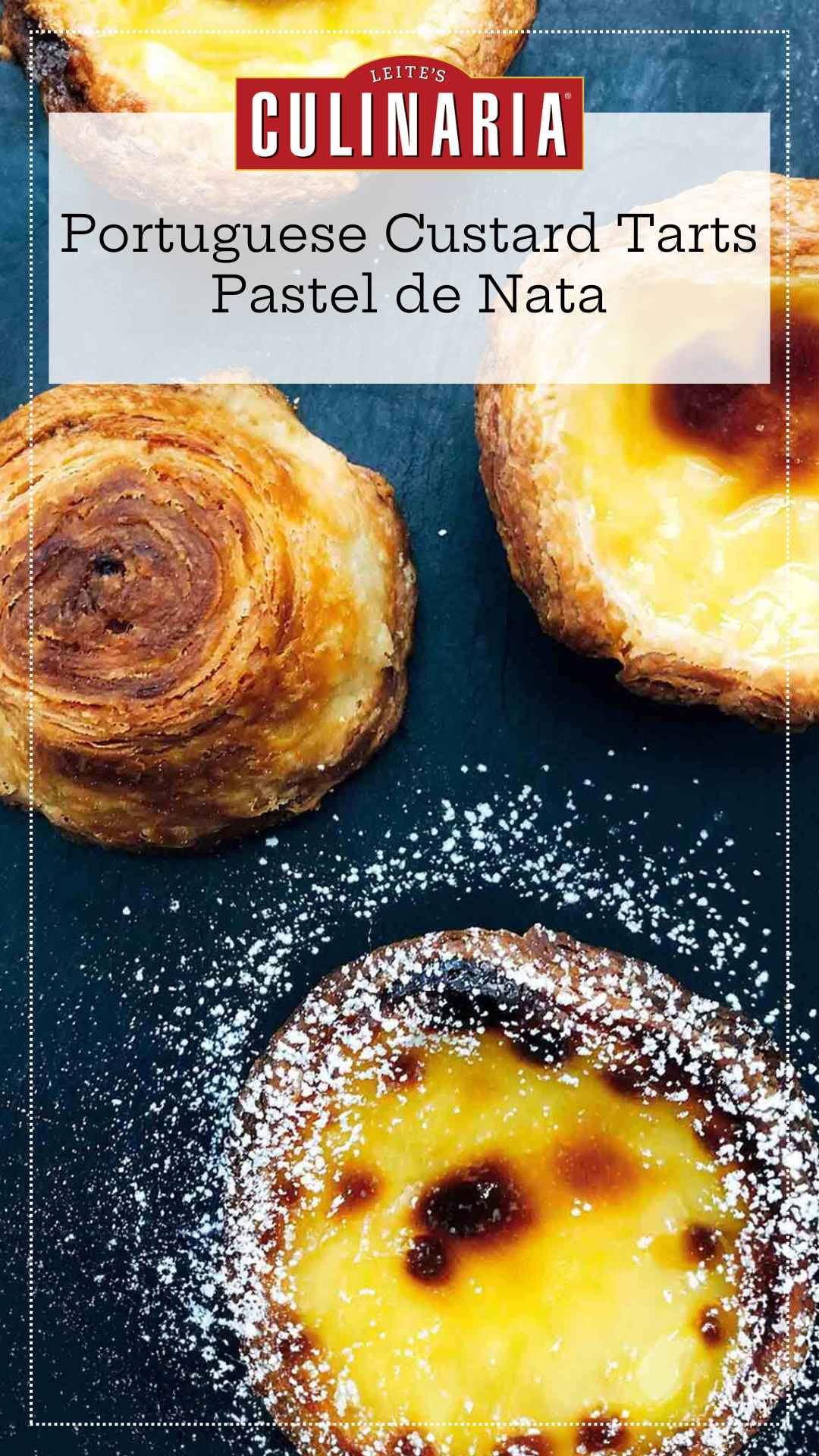

Pasteis de nata are devilishly luscious Portuguese custard tarts made with flaky pastry shells filled with rich egg-yolk custard. They were first made by monks at Lisbon’s Jerónimos Monastery sometime before 1834.

Like many Portuguese convent sweets, these tarts made use of surplus egg yolks, as egg whites were used for various purposes throughout Portugal, including starching clothes and clarifying wine.

The custard is poured into spiraled shells made from spiraled dough, similar to puff pastry, and baked until the tarts develop dark caramelized spots on top. They’re served warm with a dusting of cinnamon and powdered sugar. Alas, sadly for us, the original recipe remains a secret at the Antiga Confeitaria de Belém, where they’ve been sold since 1837.

How to Serve Pasteis de Nata

Serve these delightful custard tarts warm, ideally fresh from the oven. Dust them generously with powdered sugar and cinnamon—this is the traditional way. The perfect temperature brings out the contrast between the crispy, flaky pastry and the creamy custard filling.

They’re fantastic with uma bica, Portugal’s answer to espresso. Or you could opt for my favorite, un galão—a tall glass filled with a shot of coffee and lots of milk and foam, kinda like a caffè latte.

Common Questions

1. What’s the difference between pastel de nata and pasteis de nata?

Great question! I know it can seem confusing. Pastel de nata is a single pastry, while pasteis de nata are several tarts. Basically, pasteis is the plural of pastel.

2. How can I get those mottled black spots on top of a pastel?

Ah, the eternal question! I’ve tried all kinds of techniques to get those burnt patches on top. I baked the custard on the highest rack of the oven. I heated a baking steel and slid the pastries underneath. I even broiled them, and none gave me the “look.”

I found the only reliable way to get those beautiful spots on top is to use a convection oven (or the fan setting in European ovens).

Storage & Reheating

- Up to 24 hours, cover them loosely with plastic wrap at room temperature, though the pastry may soften.

- For longer storage, pop them in an airtight container in the fridge for up to 3 days, but beware, the pastry will definitely lose its crispness.

- Freezing? Nope. I don’t recommend it, as it can change the custard texture and make the pastry tough.

- To reheat, warm them in a 350°F (175°C) oven for 5 to 7 minutes. Nix the microwave; it makes them soggy. Blech.

Pro Tips for Pastel de Nata

- When making the pastry, make sure the butter is evenly layered, all excess flour is removed, and the dough is rolled very thin and folded neatly.

- As for the egg tart custard, you’ll need a thermometer to gauge the custard accurately.

- These are best eaten warm the day they’re made.

Write a Review

If you make this recipe, or any dish on LC, consider leaving a review, a star rating, and your best photo in the comments below. I love hearing from you.–David

Fantastic recipe, David! Outstanding reviews, and hands down the most positive comments I’ve ever heard from my neighbours and family! Thank you so much, however, now my neighbours are begging for more from me!? LOL! Such a shame to be so popular with your amazing recipe, I suppose it’s a burden that I must bear! Seriously, David, you knocked it put of the park!!

Carrots and Cream Cheese

Well, bakers, I finally did it. I improved on my pastel de nata recipe. I took me the better part of a year, but I crafted a recipe that 1.) is way easier to make (none of that endless rolling), 2.) has a creamer, foolproof custard that doesn’t curdle, 3.) sports more frilly, crispy layers, and 4.) can be frozen and enjoyed whenever your heart desires.

Get the replay of the 3-hour class, equipment list, shopping list, recipe, exclusive access to a community of avid bakers, plus monthly 1-hour complimentary live video chats with me.

Video: How to Make Pasteis de Nata

The delightful and charming London pastry queen Cupcake Jemma uses my pastel recipe to make delicious custard tarts.

Pasteis de Nata ~ Portuguese Custard Tarts

Equipment

- 1 Mini-muffin tin or…

Ingredients

For the pastel de nata dough

- 2 cups minus 2 tablespoons all-purpose flour, plus more for the work surface

- 1/4 teaspoon sea salt

- 3/4 cup plus 2 tablespoons cold water

- 2 sticks (8 oz) unsalted butter, room temperature, stirred until smooth

For the custard

- 3 tablespoons all-purpose flour

- 1 1/4 cups whole milk, divided

- 1 1/3 cups granulated sugar

- 1 cinnamon stick

- 2/3 cup water

- 1/2 teaspoon vanilla extract

- 6 large egg yolks, whisked

For the garnish

- confectioners' sugar

- ground cinnamon

Instructions

Make the pastel de nata dough

- In a stand mixer fitted with a dough hook, mix the 2 cups minus 2 tablespoons all-purpose flour, 1/4 teaspoon sea salt, and 3/4 cup plus 2 tablespoons cold water until a soft, pillowy dough forms that pulls away from the side of the bowl, about 30 seconds.

- Generously flour a work surface and pat the dough into a 6-inch (15-cm) square using a pastry scraper. Flour the dough, cover with plastic wrap, and let it rest at room temperature for 15 minutes.

- Roll the dough into an 18-inch (46-cm) square. As you work, use the scraper to lift the dough to make sure the underside isn't sticking to your work surface.

- Brush the excess flour off the top of the dough, trim any uneven edges, and, using a small offset spatula, dot and then spread the left 2/3 portion of the dough with a little less than 1/3 of the 2 sticks (8 oz) unsalted butter being careful to leave a 1 inch (25 mm) plain border around the edge of the dough.

- Neatly fold the unbuttered right 1/3 of the dough (using the pastry scraper to loosen it if it sticks) over the rest of the dough. Brush off any excess flour, then fold over the left 1/3 of the dough. Starting from the top, pat down the dough with your hand to release any air bubbles, and then pinch the edges of the dough to seal. Brush off any excess flour.

- Turn the dough 90° to the left so the fold is facing you. Lift the dough and flour the work surface. Once again roll it out to an 18-inch (46-cm) square, then dot the left 2/3 of the dough with 1/3 of the butter and smear it over the dough. Fold the dough as directed in steps 4 and 5.

- For the last rolling, turn the dough 90° to the left and roll out the dough to an 18-by-21-inch (46-by-53-cm) rectangle, with the shorter side facing you. Spread the remaining butter over the entire surface of the dough.

- Using the spatula as an aid, lift the edge of dough closest to you and roll the dough away from you into a tight log, brushing the excess flour from the underside as you go. Trim the ends and cut the log in half. Wrap each piece in plastic wrap and chill for 2 hours or preferably overnight. (The pastry can be frozen for up to 3 months.)

Make the custard

- In a medium bowl, whisk the 3 tablespoons all-purpose flour and 1/4 cup of the milk (60 ml) until smooth.

- Bring the 1 1/3 cups granulated sugar, 1 cinnamon stick, and 2/3 cup water to a boil in a small saucepan and cook until an instant-read thermometer registers 220°F (104°C). Do not stir.

- Meanwhile, in another small saucepan, scald the remaining 1 cup milk (237 ml). Whisk the hot milk into the flour mixture.

- Remove the cinnamon stick and then pour the sugar syrup in a thin stream into the hot milk-and-flour mixture, whisking briskly. Add the 1/2 teaspoon vanilla extract and stir for a minute until very warm but not hot.

- Whisk in the 6 large egg yolks, strain the mixture into a bowl, cover with plastic wrap, and set aside. The custard will be thin; that is as it should be. (You can refrigerate the custard for up to 3 days.)

Assemble and bake the pastries

- Place an oven rack in the top third position and crank the oven to 550°F (290°C) for at least 30 minutes. The oven needs this time to maintain this blazing hot temperature.

- Remove a pastry log from the refrigerator and roll it back and forth on a lightly floured surface until it's about an inch (25 mm) in diameter and 16 inches (41 cm) long. Cut it into scant 3/4-inch (18-mm) pieces. Place 1 piece pastry dough, cut side down, in each well of a nonstick 12-cup mini-muffin pan (2-by-5/8-inch [50-by-15-mm] size).

☞ TESTER TIP: If using classic egg tart tins, cut the dough into generous 1-inch (25-mm) pieces. Allow the dough pieces to soften for several minutes until pliable.

- Have a small cup of water nearby. Dip your thumbs in the water, then straight down into the middle of the dough spiral. Flatten it against the bottom of the cup to a thickness of about 1/16 inch (1.5 mm), then smooth the dough up the sides and create a raised lip about 1/8 inch (3 mm) above the pan. The pastry bottoms should be thinner than the tops.

- Fill each cup 3/4 full with the cool custard. Bake the pastries until the edges of the dough are frilled and brown, about 8 to 9 minutes for the mini-muffin tins, 15 to 17 minutes for the classic tins.

- Remove from the oven and allow the egg tarts to cool a few minutes in the pan, then transfer to a rack and cool until just warm. Sprinkle the pasteis generously with confectioners' sugar, then ground cinnamon and serve. Repeat with the remaining pastry and custard. These are best consumed the day they're made.

Notes

- Pastry making–When making the pastry, make sure the butter is evenly layered, all excess flour is removed, and the dough is rolled very thin and folded neatly.

- Tending to the custard–You’ll need a thermometer to gauge the custard accurately.

- Timing–Portuguese egg tarts are best eaten warm the day they’re made.

Variation

If you’d like a citrus kiss to your custard, add two 2-inch lemon peels along with the cinnamon stick in step 10.

An LC Original

View More Original RecipesNutrition

Nutrition information is automatically calculated, so should only be used as an approximation.

Recipe Testers’ Reviews

According to my Portuguese dad, I can make these pasteis de nata again and again and again! I am pretty chuffed with how they turned out since I had doubts throughout the entire process of making these traditional tarts. First of all, pasteis de nata are the epitome of the classic Portuguese sweet treat. So, no pressure!

In following the recipe, when mixing the flour, salt, and water in the stand mixer, my dough never achieved the soft pillowy stage I was hoping, or rather thinking, what it would be. My dough did pull away from the sides slightly but remained sticky; hence I feel I should have added more flour, which I didn’t at this stage.

Doubt started to set in! When working with the dough on the work surface, I needed to add a very generous amount of flour to stop the dough from sticking. At this stage, I probably added so much flour that I actually increased the amount of flour added to the dough significantly.

I found working with the dough a test of extreme patience! I remained calm (yet doubtful) and just kept working with it gently. I was never able to achieve the 18-by-18-inch square, no matter how hard I tried. It was closer to 14 inches.

The custard seemed quite thin, and even though the recipe mentioned it would be, I had my doubts it would firm up into a creamy custard.

While the tarts baked, the butter bubbled and oozed out of the dough and over the edge of the minis tin, causing lots of smoke in the extremely hot oven. I baked the minis for 9 minutes, and the custard was set, and the pastry was golden brown. I expected the custard to have a brown-speckled appearance (like the ones you buy commercially), but it remained an eggy yellow. For the larger tins, I baked the tarts for 15 minutes, and they, too, remained an eggy yellow with a golden brown pasty.

To my surprise, the pastry was super flaky and crispy, and it had that perfect crackly crunch that is the true mark of a great pastel de pata! And the custard? It set and was creamy, sweet, and deliciously perfect.

When my Portuguese mom said they tasted just like the pasteis de Belem (the most famous and original Portuguese custard tarts), then I knew we had a winner!

Talk about the best compliment ever! It was quite a bit of work to produce these little gems, but the end result was definitely worth the effort!

Well, if they’re using margarine (invented circa 1870), then they are certainly not sticking to the original 1837 recipe 😉

Not from the recipe from the Monastery of Jeronimos! My guess–and I can’t confirm this with anyone at the confeitaria–is that it was a 20th-century tweak. It’s called margarina para folhados, which is, apparently, different from margarina para bolos, etc.

Yeh, the nubs vary a bit depending in width depending on the roll, but usually with my mini cupcake pan it’s 1/2”-3/4” thick.

About the mixing the fat–I bet they don’t use butter at all, but rather leaf grade lard (or a mixture of the two as you say). I’ve never worked with leaf lard or even seen the correct cuts of fat to render into leaf lard (it comes from around the kidneys, not the fat back from above the shoulders), but it is supposedly the holy grail of pastry cooking fats. You often hear chefs in the States talking up European butters, especially for puff pastry, because it contains less water and more fat than American butters. I don’t know why exactly leaf lard is supposed to produce such flaky pie crusts and shatter-tastic croissants, but it’s probably got to do with its even higher fat and lower water content.

I can say for sure that it’s not leaf lard or regular lard. It’s actually a margarine-like product. It’s very yellow. My guess is it’s a combination of butter and some form of hydrogenated fat.

This is the only puff pastry recipe I know of that uses an almost 1:1 ratio of flour to water. I don’t know if this is a Portuguese thing or unique to these pasteis, however, there are many different puff pastry recipes that are much easier to work with. Most puff pastries contain water at roughly 55-60% of the flour total (that’s a baker’s percentage). It will make for a much less sticky dough and eliminate the need to so generously flour the rolling surface.

Hi, Peter. I got this recipe from a Portuguese baker, who got it from his predecessor–both of whom are from Portugal. It’s absolutely a different dough from traditional puff pastry. And it’s the only puff dough I know of that uses room temp butter. I’m not a math genius, but according to my calculations, the water is 47% volume as compared to the flour (14 tablespoons of water to 30 tablespoons of flour.) It’s not a 1:1 ratio, but almost a 1:2 ration.

Baking ratios are typically done by weight, not by volume. So, 2 cups minus 2 tbsp flour is equivalent to approximately 230g of flour and 3/4 cup water plus 2 tbsp is 205g of water. 205gH20/230g flour is approximately 89% water as a percentage of flour (a baker’s percentage). So, it is almost 1:1, if you follow me.

I made it both ways and the traditional puff pastry recipe is much better and easier to work with than the method described here. Other recipes for pastel de nata or pastel de belem tend to follow the more tradition 55-60% water as a percentage of flour for the puff pastry. This custard filling recipe is spot on, the flour really helps prevent curdling of the milk under the high heat that the pastel de nata require.

Peter, I definitely got your point. And, yes, I measured by volume, my bad. I’ve never had a problem with the dough, though. Did you know that in Belém the dough is made in a log that’s about one foot in diameter and then pulled and pulled until it’s an inch in diameter? I wonder if the extra water helps that process.

So tell me, would you consider sharing your recipe for puff pastry so that we can offer it as an option for readers?

I’m happy you like the filling. I think it’s quite good.

The recipe is same as yours, just less water (if you’re using AP flour, you’ll want 125ml-135ml of water). I also do the traditional butter square thing as opposed to this room temperature spreading stuff. It’s not really my recipe, just a basic puff pastry recipe you’ll find in almost any culinary guessing book. There’s also an America’s Test Kitchen episode where Julia (one of the cooks) builds the puff pastry using a jelly roll pan and parchment paper making it virtually impossible to screw up.

As for the stretchiness, as far as I know, the elasticity of flour is affected by only the gluten content and the amount of kneading (and to a lesser extent, things like salt and acid). Typically, puff pastries are kneaded very little so as to avoid gluten development, some folks even recommend adding a bit of acid to keep the gluten from developing. I imagine an expert pastry baker would be the person to consult on this sort of thing though–as I understand it, those Belem bakers are rather secretive with their recipes.

Secretive? Secretive?! The dough and custard are made behind a locked door at night. I did discover they also use a fat that isn’t 100% butter. I forgot the name, but it can be bought in Portugal.

But I assume you roll your puff, cut it into 1-inch nubs, and turn them on their cut sides in order to thumb the dough up the sides of the tin?

Ola David, a gordura que eles usam em portugal para a massa folhada dos pasteis de nata e margarina para folhados.

Olá, Maggie. Em Portugal eles usam um produto similar a margarina. Eu não sei a real composição do conteúdo de gordura, mas tem um ponto de fusão mais elevado do que a manteiga. E faz um bolo mais esquisito. Mas elas única coisa é que é um transfat.

Ola David, desculpe de incomodar mas sera que me podias esplicar a causa de a massa folhada encolher quando vai para o forno ? e que ja me passou varias vezes e o creme entorna e os pasteis ficam perdidos. outras vezes ficam mesmo uma maravilha. Obrigada.

Maggie, obrigado pela sua mensagem. Retracção é causada pela massa sendo manipulado muito. A massa precisa descansar na geladeira o tempo suficiente para que o glúten pode relaxar. Além disso, quando você está moldando a massa até os lados da estanho de cozimento, certifique-se de não puxar muito nisso, ou ele vai encolher. Você também pode cortar os pedaços de massa um pouco maior para que você tenha mais massa para trabalhar com comk. Espero que ajude.