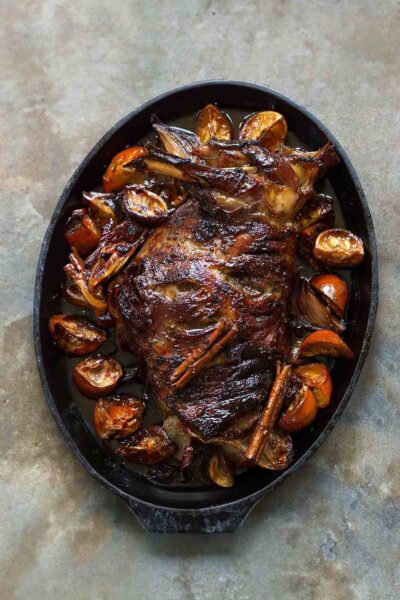

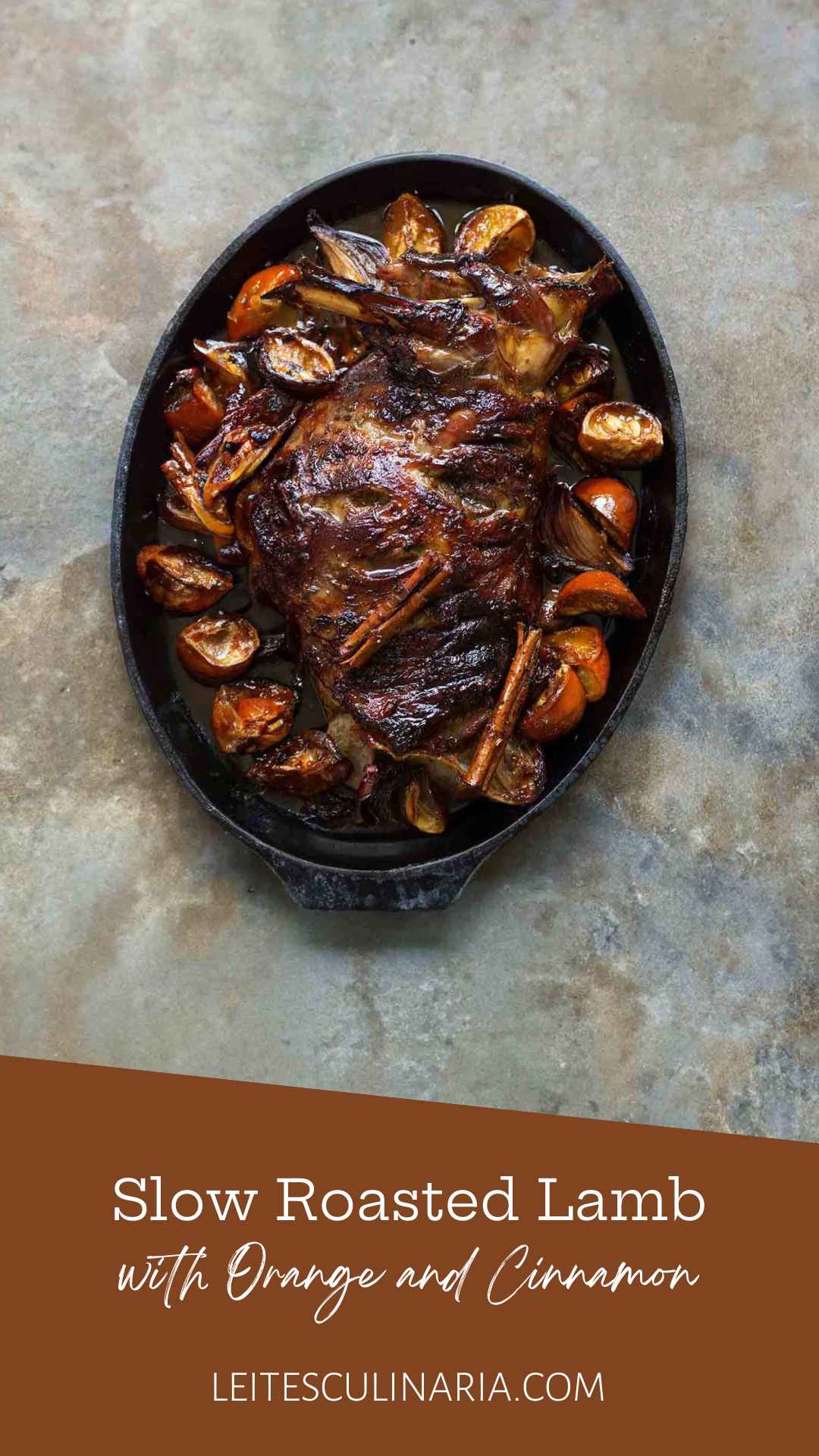

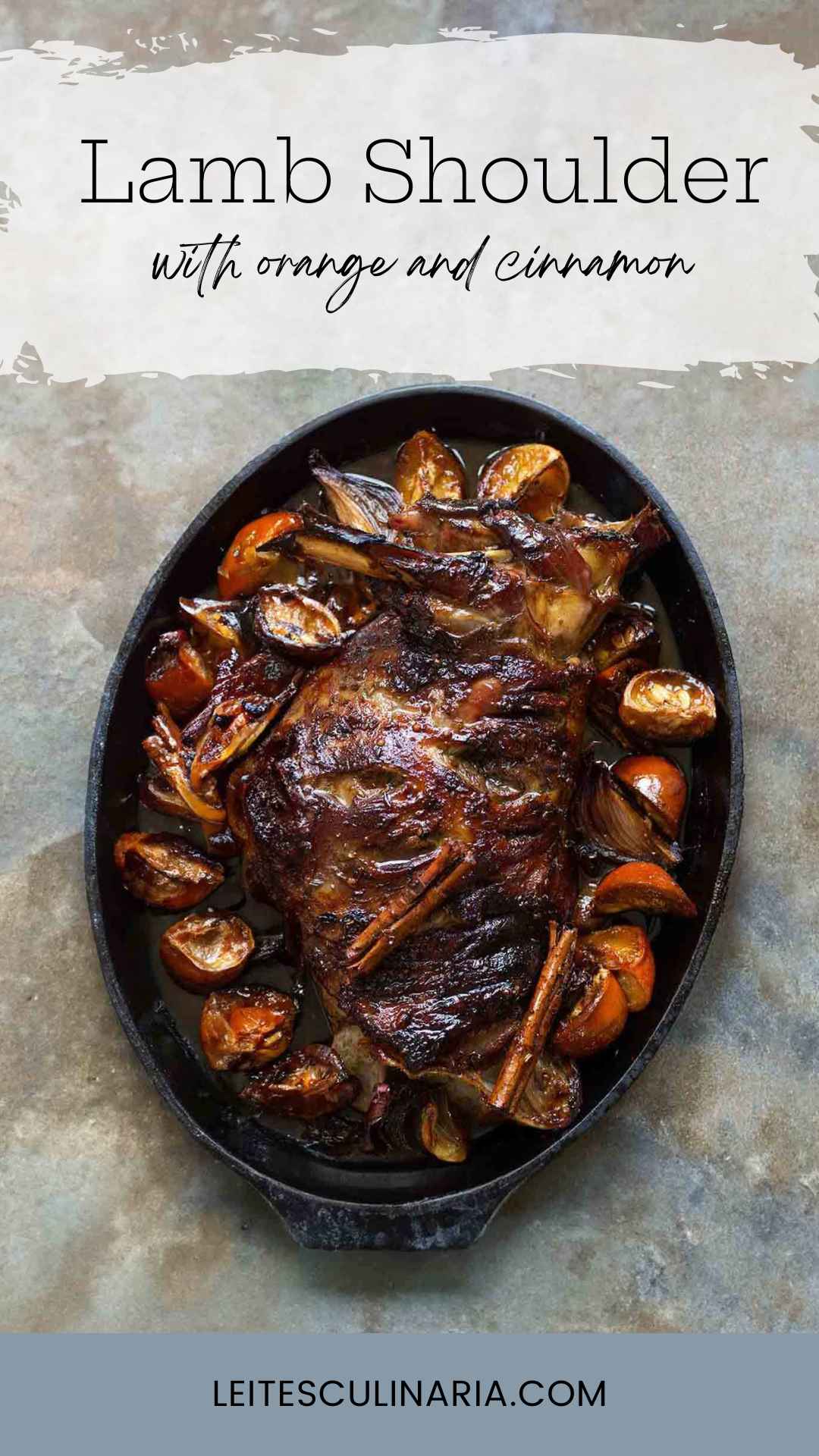

This slow roasted lamb shoulder cooks low and slow, gently intensifying the flavors and coaxing the lamb to fall-apart-tenderness. And it couldn’t be any easier. Just toss some ingredients together, let them mingle in the fridge overnight, then toss it in the oven and forget about it for a few hours. It’s ideal for turning out an impressive Easter lamb dinner.

Even better, notes author Annie Rigg, there’s no need to fuss with making gravy since the onions and oranges create such beautiful pan juices.–David Leite

Why do I need to let my lamb rest?

Essentially, by letting the meat rest before slicing, you’re letting the protein fibers relax and the juices redistribute within the meat instead of all over your cutting board. Not resting your roast lamb, or any meat for that matter, is a common mistake that really does hinder taste and texture. If you’ve avoided doing it because you think you’re just gonna end up with cold lamb, then you’re in for a pleasant surprise.

We’re not telling you to leave it on the counter for hours—a 10 to 20 minute rest is all you need—loosely tent it with foil and get the rest of dinner ready. You can even put it on a pre-warmed platter if you’re really worried about heat loss.

Slow Roasted Lamb

Ingredients

- 1 heaping teaspoon cumin seeds

- 1 heaping teaspoon fennel seeds

- 2 small dried red chiles

- 1 teaspoon ancho chile powder or smoked paprika

- 3 tablespoons olive oil

- 3 tablespoons honey

- Salt and freshly ground black pepper

- 4 1/2 pounds bone-in lamb shoulder*, (or substitute boneless leg of lamb)

- 3 medium (about 1 lb) red onions, peeled and cut into wedges

- 2 Seville or bitter oranges, scrubbed and dried, then quartered (or substitute 1 thin-skinned orange and 1 thin-skinned lime)

- 2 heads garlic, unpeeled and halved horizontally

- 1 cinnamon stick

- 2 tablespoons pomegranate molasses

Instructions

- In a small, dry skillet over low to medium heat, toast the cumin seeds, fennel seeds, and dried chiles until they start to become aromatic, shaking the pan almost constantly so that they toast evenly, about 1 minute.

- Lightly grind the toasted spices using a mortar and pestle but be careful not to reduce them to a powder. In a small bowl, combine the ground spices and chiles with the chile powder or smoked paprika, olive oil, honey, and salt and black pepper to taste.

- Using a sharp knife, cut 5 to 6 slashes into the lamb shoulder. Place the lamb in either a 2-gallon resealable plastic bag or a roasting pan and rub the spice mixture into the meat. Add the onions, oranges, garlic, and cinnamon stick. Massage everything together so that the meat is really well covered and then either seal the bag or cover the meat.

- Stash the lamb in the fridge for at least 8 hours or overnight. (Ideally, you’d flip the lamb occasionally to keep it evenly coated with the marinade, but this isn’t going to make or break your roast.)

- The next day, preheat the oven to 375ºF (191ºC). Place the lamb on the counter.

- If using a plastic bag, dump the lamb and the rest of the contents of the bag into the roasting pan. Make sure the lamb is skin-side up and that there is an even distribution of onions, oranges, and garlic around the meat, doing your best to keep the onions in intact wedges if possible. Roast the lamb, uncovered, for 20 minutes. Then cover the roasting pan tightly with foil, reduce the heat to 300ºF (149ºC), and cook until the lamb is tender and registers 160°F (71ºC) if you prefer medium doneness or 175°F (79°C) for fall-apart tenderness, which ought to take anywhere from 2 to 2 1/2 hours. Be aware that leg of lamb will take less time than lamb shoulder. If you are cooking leg of lamb and prefer tender, medium-rare meat, remove it from the oven when the internal temperature is 140°F (60°C).

- When the lamb reaches the desired temperature, take it out of the oven and crank the oven back up to 375ºF (191ºC).

- Uncover the lamb, spoon the pomegranate molasses over the top, and then spoon the pan juices over the lamb while you wait for the oven to reach 375°F (191ºC). When the oven reaches temperature, slide the lamb and roasting pan back in the oven and cook, uncovered, until it’s nicely browned and sticky, 10 to 20 minutes.

- Loosely cover the lamb with foil and let it rest in the pan on the counter for a good 20 minutes.

- Meanwhile, using a slotted spoon or tongs, gently move the oranges, onions, and garlic to a plate. Strain the juices from the roasting pan into a fat separator or a bowl and set them aside until the fat rises to the surface. While the juices rest, squeeze some or all of the garlic cloves into the strained juices or reserve the roasted garlic for another use. If you used a Seville orange, you can finely chop it and scatter it atop the lamb for modest bursts of sweetly sour loveliness.

- When the lamb has rested, carve it as thickly or thinly as you please or grab a couple forks and use them to pull the meat from the bone into shreds. Pile the lamb on a platter. Serve it with the pan juices poured over the lamb or passed on the side.

Nutrition

Nutrition information is automatically calculated, so should only be used as an approximation.

Expanding on Angie’s comments: those lamb and beef cuts that are cooked to 130 degrees are generally from the animal’s muscles that are soft because they don’t do much work and are usually a single muscle-like a rib eye or loin chop. They are quickly cooked at very high temps. Cook those at high for too long and it gets very tough. Shoulder on the other hand does a huge amount of work and therefore is quite hard, and is comprised of many muscles that are held together with all manner of connective tissue. The tough connective doesn’t begin to break down until around 165 degrees and the tough meat not much lower. So it takes hours. If you cook shoulder at high temperature fo a long time , it will dry out. So, shoulder is cooked at low temperatures for a long time.

Thanks, Neal. That’s very helpful.

Neal, I greatly appreciate this!

Hello, please clarify my confusion re lamb and internal temp. I see several recipes in this group and other lamb recipes that call for internal temp like beef, about 130 with notes not to overcook else dry and tough. But then other recipes such as this one calls for internal 170+ for tender fall off bone meat. I am not clear as to different internal temps giving both favorable and unfavorable results depending on the recipe. If the shoulder roast is used it’s more understandable but if using a leg, why isn’t it dry and tough at such a high finished internal temp? Thank you for helping me understand this.

Den, for this particular recipe, if you’re using leg of lamb, you’ll want to aim for a lower internal temperature, depending on your preferred level of doneness. The original recipe was written for lamb shoulder, which benefits from a higher internal temperature to achieve that falling-apart tenderness, but the leaner leg cut can be cooked to a temperature of 135 to 150°F, depending on how you like it. It will likely be a little tough if you cook it to 170°F. I will add a note to the recipe to clarify this.