She Said:

I have a thing for everyday loveliness. When I was little and my mom baked batches of bread, I’d coyly request a slice while it was still warm from the oven…and always from the loftiest loaf. In high school, I opted for cross country’s winding gravel roads rather than track’s monotonous cinder loop. As a New Yorker, I took my time walking through Central Park every chance I could rather than taking the subway. And when, on rare occasion, I took the train home, I’d hop off a stop earlier than I ought, lugging my groceries several extra blocks just so I could emerge amid a cobblestone square with trees rather than the usual sidewalk squalor.

It only seems fitting that I’d be drawn to recipes with a little character. Those far-and-few-between recipes that play loose and easy with language, that dance to their own rhythm of style and grammar, that are imbued with a touch of the writer’s personality.

It’s not that I can’t appreciate the practicality of bullet-pointed recipes in severely succinct language that lets pretty much everything fall to the imagination. I understand. It’s tremendously efficient. Like the shortest way home from the subway. But that approach, quite frankly, bores me. And often leaves me bereft of subtle nuances that could make my understanding of the recipe more complete. So rote are the minimalist recipes with uninspired instructions that even copyright law renders them outside of legal protection, deeming them indistinguishable from one another. It’s only when a writer inextricably interjects her or himself into the instructions, rendering instructions into prose, does a recipe transcend into the realm of copyright-legit art.

I’m not talking longwinded headnotes. And I’m not suggesting a recipe need be poetically epic to be suffused with personality. It can still be simple. Take the succinct recipes penned by the inimitable Laurie Colwin. She memorably blurred the line between ingredient list and instructions, which may or may not appeal to you, yet it’s undeniable that she was fluent in the language of the everyday and all the little annoyances and pleasures that take place in the kitchen. We benefit not just from her culinary expertise, but from her life. Note, if you will, how she channels Katharine Hepburn’s brownie recipe in just four dozen or so words.

There are, of course, others. M. F. K. Fisher. Ruth Reichl. Judy Rodgers. Fran Gage. Whether softspoken, plainspoken, or outspoken, each of them knows how to linger over a description that mirrors their thoughts, their cooking experiences, and, at times, some measure of their very being. Take Gage, who in The New American Olive Oil disregards more humdrum standardized descriptions for caramelized onions and instead paints them “the color of a polished mahogany table.” How helpful to the novice cook to have this explained in recognizable terms rather than simply and rather offhandedly be instructed to “cook until caramelized.” And what a lovely little interlude to happen upon while in the midst of making supper.

Perhaps we’d all save a few seconds here and there if we dispensed with extraneous adjectives and explanations and set them aside to appreciate during a less rushed day. But here’s the thing: You may have every intention of doing so, but that sometimes doesn’t happen. Life goes by pretty quickly. I prefer to cling to what loveliness there is when it happens, even if that means taking a slightly longer glance at that batter-splattered recipe ripped from a magazine long ago.

[renee-signature]

He Said:

Laurie Colwin. Kate Hepburn. Fudgy brownies. Mine is a losing proposition, if I ever saw one. If one of us is going to get strung up in the public square and poked with the business end of sharp farm tools, it surely isn’t going to be Renee. But here goes.

I enjoy beautiful words as much as the next cook. Maybe more, being a writer. I’ve banged my head against the wall countless times trying to find descriptive ways of explaining to you, dear readers, what a perfectly griddled pancake looks like or when onions are at a precise state of wilted-dom. But I’ve got to tell you, I like the division of church and state—or in this case, art and craft.

Gorgeous language is entirely welcome in a recipe, but come on—for God’s sake, not in the directions. Let’s keep it relegated to the headnote. That’s where all of the everyday prettiness—the art—Renee loves should live.

Now, I’ve never seen Renee cook, but I imagine it’s probably an act of supreme Zen meditation. I see her humming a Gershwin tune softly to herself, thrumming her fingers on the counter as she leans over a recipe, smiling at all those conjunction junctions, hooking words and phrases and clauses and making them function. I wouldn’t be surprised if woodland creatures gather at her feet while birds twitter around her head, so at one with the prose is she. And the actual act of putting together a meal? Sheer fluidity Martha Graham would envy, I’m sure.

I, on the other hand, have every intention of cooking like that, and I always start that way. But 20 minutes later, I’ve usually discovered I’ve forgotten something at the grocery store, so I have to stomp around looking for a replacement. The One then asks, for the tenth time, “When will dinner be ready?” As the tension escalates, you’d think my cooking motto, no doubt brazenly tattooed across my ample chest, is, “No pot left behind,” because the counter, sideboard, and kitchen table are strewn with dirty cookware. And the sad thing is I’m the one who lives in the country part-time with a yard of woodland creatures. I’m the one with a huge kitchen. But with all the clanking of pans and cursing to the fates, nary a bird would dare cross our property line.

What does all of this have to do with the way a recipe is written? A lot. I like a recipe to be clear, concise, descriptive, and orderly—that’s the craft. I want to get in and out and get on with it. But that’s a hard thing to do when the ingredients list is embedded in the directions, like Colwin is wont to do. Huh? Or when there’s a lot of chatty Cathy me-me-me narrative going on, and I have to keep returning back to the recipe, wooden spoon dripping olive oil everywhere, while I run my index finger down the page trying to find my place again. I don’t mind snuggling up to a writer, having her take me by the hand through her recipe, her cooking domain. But when I have to sift through anecdotes about her husband’s eating habits and her kids’ preference for dark chocolate in between steps six and seven, it just mucks up the cooking process.

Speaking of numbered steps, I can’t fathom why so many recipes are bereft of them. Numbers are what make society run. (Try not having a social security number, license number, telephone number.) And they have an elegant logic that’s utterly failsafe: two follows one, three follows two, which follows one, and so forth. When a recipe is numbered, it makes for (pun intended) an easily digestible chunk of text. And face it, when you’re making cassoulet from LC recipe tester Cindi Kruth, you better believe you need plenty of number steps to make it through the end without plunging your head into duck fat and ending it all. For me, in the kitchen at least, it’s just the facts, ma’am.

Now, get me away from the stress of cooking a complicated, three-day recipe, or the frenetic pace of a quick weeknight meal, and I thoroughly enjoy being seduced by a recipe, my senses being tickled by letters that become words that become sentences that become, in the end, joy. But like most of my best reading, it’s done prone—in bed, on the couch, on the floor, in a chaise on the patio. Definitely not while standing facing the stove. Originally published June 25, 2010.

Tell us: What kind of recipe do you like?

Are you the sort of home cook who gets lost in the lyricism of a recipe? Or do you prefer to just glance at a recipe so you can keep focused on the task at hand? Let us know in a comment below.

You know, to be honest, I do prefer a recipe that converses with me rather than mere dictation. It doesn’t even have to flourish or poetic, I just find it very comforting when I read a recipe that makes me feel like the author’s in the kitchen with me, chatting alongside as I cook while sipping on a glass of wine. Case in point, Thomas Keller’s Poulet Rôti which reads: “[…]Remove the twine. Separate the middle wing joint and eat that immediately. Remove the legs and thighs. I like to take off the backbone and eat one of the oysters, the two succulent morsels of meat embedded here, and give the other to the person I’m cooking with. But I take the chicken butt for myself. I could never understand why my brothers always fought over that triangular tip—until one day I got the crispy, juicy fat myself. These are the cook’s rewards.” A recipe like this makes cooking seems much less a chore than it sometimes feels like.

An, now to me your example straddles both sides. It’s narrative and first-person, BUT it offers up all kinds of info the cook many not know: what an oyster is on a chicken, how tasty the bishop’s (or pope’s) nose is. Craft and function meet beautifully.

Such a lovely sentiment, An. Yes, something that takes you a little or a lot beyond your own experience and allows you a glimpse of something more, whether it simply makes you stop for a moment and smile or even informs your cooking going forward. And yes, a chicken butt beats a chicken oyster any day!

I’m going to have to go with you on this one, David.

Some of my favorite cookbooks impart wonderful stories of travel, history, culture and anecdotes, but NOT in the instructions. I want my instructions clear, concise, and in (numbered) order. Wax poetic in the head notes. Heck, take up several pages BEFORE the recipe, even, but don’t sidetrack me in the middle of caramelizing garlic with long-winded descriptions and side notes.

And while I’m on the subject of usability, this trend toward shadowboxing, tinted (rather than black) text, and cute/fancy and tiny fonts is extremely annoying. I should not need a microscope and decoding ring to read a font, nor should I need to scan a recipe from a book and tweak the contrast in order to read it. If the average person can’t lay the book on the counter and follow the text without resorting to a ruler, the font isn’t clear enough.

I won’t mention the author, but I was gifted with two baking books that are supposed to be excellent. I’ll never know because the font is so small and the contrast between text and background so weak that they are unusable as cookbooks. I might sit down and read them, but I know I’ll never bake from them. I tried giving them to someone else, and she said she would never use them for the same reason.

When the purpose is to give specific information while the person is in the middle of the activity, function trumps form

Renee, no need to feel bad for being…right!

Hi, all. I’m an editor and instructor, as well as an LC tester, so clear directions are de rigueur for me—not that I don’t mind the occasional imagery-filled headnote or set of comments.

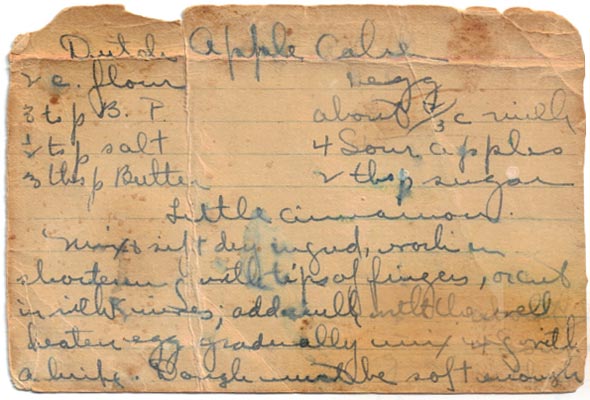

But, ahem, aside from the debate, may we please have the rest of the Dutch Apple Cake recipe hinted at in the picture, with its stains and splotches showing evidence of a much used and loved copy? Is the source the one who wrote it in such an assured hand, confident he or she did not need numbers to recreate a handed-down family favorite?

Oh my Dears! Can’t you see it? You are BOTH right on target – it’s just that the target is moving. And if, like me, either of you happens to fall into ADD-dom, then you know we need both of you with us in the kitchen! Renee, you are the one that keeps us “interested” and going from word to word – yes, David, humming all the way. However, when we finally remember we are cooking here, – help! we need the number of the last step we did (I know it must have have been a waltz this time) so we can continue. And that poetry in recipe is such a part of the good ole down South (way down yonder in New Orleans and environs) that we are enraptured by descriptions of roux that are either dark chocolate brown, wet brown-bag like, or just a touch sun-kissed as a good white sand beach. I wouldn’t know how to do it otherwise – I depend on that poetry right there in the recipe. It is as if my mind is taking the word and painting the picture so that the pan matches the instruction. So, I say thank you to both of you as I happily skip across the kitchen to try to find that weird pot thing (wok on top?) that is mentioned in Step 4 or Step 5, but alas no where in the list of what I need to get this orchestrated and on stage in dining room!

Karen, so much wisdom in your words. And I wish I could dally and enjoy the language while cooking. And I do many times. But the fancy of many writers to become overly chatty in the recipe steps makes it hard for me. Go to town in the headnote, I say.

A case of protesting too much here, David. A quick perusal of this site or your gorgeously written The New Portuguese Table, shows you compose lovely recipes. But I know what you mean. A “burble” or “thickens lusciously” while distinctive and descriptive is not a long-winded pretty distraction, but rather a helpful image.

I, of the accused cassoulet recipe, am also glad you mentioned numbers. In fact, not only do I love numbered steps, I believe there are too few of them in most recipes. I understand the demands of cookbook editors. Well, I know what they are. I don’t truly understand. Why for example is “ Whisk flour, sugar, baking soda, and salt together in large bowl. In separate bowl, combine cocoa and chocolate; pour hot coffee over cocoa mixture and whisk until smooth; let cool slightly. Whisk in mayonnaise, egg, and vanilla. Stir mayonnaise mixture into flour mixture until combined. ” (from a Cook’s Illustrated recipe for mayonnaise cake) all one step? It’s practically the whole recipe. Is there some unwritten “maximum of 5 steps and they all have to fit on one page” rule?

Recipes I write for my classes always scare my students at first. So many steps. But the recipes are no longer. I merely break down the instructions into what IMHO are self-contained steps. “Sift together the flour, salt, and baking soda” and “fold it into the egg mixture” may be one step. But directions for beating the egg whites until frothy, adding cream of tartar, beating until soft peaks form, gradually adding sugar, and continuing to beat until it becomes a stiff glossy meringue will not be in that same step. These techniques, in fact, are individual lessons. Many students check off the steps as they proceed, thus making sure not to lose their place.

Oh, yeah. I’m finicky about order too. Steps should be in the order they are needed. Trust me, no matter how many times you instruct students to read the entire recipe through before beginning and to mise en place both ingredients and equipment, they won’t. If they get to step 6 and it calls for adding 8 ounces (I’m a nudge about weight measurements too.) boiling water that water had better be listed in the ingredients and the boiling of said water better be somewhere in step 1-5 or 10 minutes into the recipe there will be 15 students running around putting pots of water on the stove. Ditto, preheating the oven.

So, I’m with you. A good headnote can provide both lovely images and information vital to the proper execution of a recipe. I love reading beautiful food writing too. Just not in the middle of a recipe.

Cindi

Spot On, Cindi!!

I am one of those of whom you speak (and giggle at perhaps, or tear your hair?) who is just NOW, thanks to LC, learning to mise en place everything – including my recipe! I have learned so much already, and each new recipe brings another perspective to cooking and food. All in all, I am one who benefits greatly from “short descriptions” included in the recipe. I use my all time favorite of the first time I tried to cook and the recipe told me to “cook until done” and I had not one clue what “done” was supposed to look like, feel like, or taste like. My definition of cook until done was when the spoon stood straight up in the pan untouched by human hands and/or the cook threw in the towel and went out to dinner. A little description (either time wise, appearance wise, behavior, or tastes like) would have been most helpful. I have learned a lot since then…

Cindi, I completely agree with you. It’s much easier to figure out where you are in a complicated recipe if there are delineations of the process. I also list my ingredients in order of need in the recipe and leave a blank space between each “set” of ingredients needed for specific steps.

Some of my own pet peeves are lack of correct/logical abbreviations in recipes. These were taught to me back in the dark ages, when I was young. Examples: tsp for teaspoon, TBS for tablespoon, oz for ounce, lb for pound etc. These abbreviations for tsp and TBS especially are important to me. I have a tendency to read too quickly (adult ADD) and if the difference is evident, then I won’t mistakenly put a TBS of something in when it should have been a tsp.

I also think recipe writers need to remember that a lot of readers are beginners and need extra information. If it says 1 TBS of basil, is it dried or fresh – 1/4 lb of butter, is it salted or unsalted? No one should assume everyone else knows all the rules that you learned over the years.

Helpful descriptions are fine in the instructions, but leave the prose to the header.

Zanne