Quick. What comes to mind when you think of stock?

Sadly, a lot of us think of tin cans or waxy boxes. From their shiny, happy faces, the packages shout “All-Natural,” “Lower Sodium,” Rich-Tasting.” But then I take a swig—yes, I swig broth—and the truth is revealed.

Sure, some are, indeed, lower-sodium—when compared with a salt lick. But the murky liquid inside is a flatliner, one with nary a pulse of flavor, despite being riddled with octosyllabic ingredients that sound as if they belong in automobile lubricant.

Shame, shame on us.

It doesn’t have to be that way. Homemade stock, simmered for hours with as many bones as you can cram into the pot, isn’t only trés facile to make, it’s a thing of beauty, filling the house with the unmistakable scent of nostalgia.

Standing in front of that burbling pot, the steam opening your pores and filling them with its animal essence, you have a sense of purpose. You feel like one of those earnest people in wartime posters, wrench in hand, ready to defeat the Axis powers and be back at the table in time for dinner.

In my case, dinner is our annual cassoulet dinner party. A casual affair, the party was started years ago by friend and LC recipe tester Cindi Kruth after one of those cloud-parting, angels-singing epiphanies in France when she first tucked into a crock of slowly simmered beans, sausage, and duck confit, all melded together by, of course, stock.

Since then The One and I have had the pleasure of being invited several times to sit at her table, shoveling bowl after bowl of her marvelous creation—a recipe she’s been perfecting since her Divine Intervention—down our gullets.

This year, though, thanks to dwindling numbers of guests and her dwindling waistline, she handed the duck fat-slicked baton to me. “Your turn,” is all she said. Fine, I thought. Imaginary wrench held high, I vowed to make a cassoulet for the ages. And that’s how I got the crazy idea to make homemade duck stock.

Ah, but not just any homemade stock. A stock that was intensely flavored, rich, and gelatinous. A stock so lovely, it would be a shame to cook with it. An über stock.

That meant getting hold of a hell of a lot of duck bones. Meaty duck bones. (Both meat and connective tissue contain collagen. When gently heated in water, the collagen dissolves, causing the stock to turn into shimmying jellied gold.)

Not having a freezer filled with duck parts meant one thing: a call to D’Artagnan. Although mostly sold to restaurants, meaty duck necks—the prima ballerina of stock ingredients and soooo much better than strip-mined duck carcasses—can be had for a reasonable price. Call and say, sotto voce, that David sent you. The only problem? The duck necks come exclusively in 25-pound boxes.

Nothing tests your stock-making resolve like a 25-pound box of frozen fowl. I was worried that the hardest part of my endeavor would be justifying to The One why I’d bought a box of duck necks the size of a library desk with our joint credit card. He just shook his head when he saw me stumble into the house—the resigned shake that only years of slamming into an immovable object can produce—and slumped out of the kitchen, muttering. But that was piffle next to figuring out what I was going to do with all those necks.

After seriously questioning my deductive reasoning, I ferreted out my dusty canning pot that has doubled as a washtub at times. Then I heaved it and a pasta pot onto the stovetop. Those, I was sure, would be big enough to accommodate all the bones.

I decided to first ratchet up the flavor quotient by roasting the necks in a hot oven. I wasn’t sure what to expect but found myself dancing a happy jig when I noticed crusty, caramelized bits forming in the roasting pan. That drew The One into the kitchen, just like the giant animated aroma finger that beckoned Sylvester the Cat. Suddenly, my credit-card charge doesn’t seem so foolish after all, does it, mister?

I loosened up the cracklings with a splash of water and dumped all that browned goodness into a waiting pot of cold water. He grew more curious, moving in closer, but I pretended not to notice. A little punishment never hurt anyone.

I resisted the urgings from cookbooks and chefs to add shallots, leeks, and onions to the pot. Or tomatoes and tomato purée. Or handfuls of sage, thyme, rosemary, and marjoram. Too much trumping up, thank you. I wanted a duck flavor so unadulterated, its feathers would seem to flutter on your tongue. I settled upon onions and carrots for an undercurrent of sweetness, garlic for the wee-est bite, and a tiny, tiny amount of tomato paste for a hint of umami. Fini. Acabado. Done.

Then came the simmering, which isn’t my bailiwick. I do few things at a simmer. It’s just not fast enough. I don’t even simmer at a simmer but rather at a moderate boil. Patience, darlin’, thy name is not David. But I knew that anything more than a slothful burble, the kind that sends up bubbles so infrequently it forgets what it’s doing, would cloud the stock with a foam of impurities from the meat and bones. So down went the heat and up went the spoon as I stood there, waiting, waiting, waiting for the scum—such an unfortunate food word, scum—to form and get all that grossness the hell out of there. Fidgety, I contemplated cranking the heat to a boil more than once, but that would only have defeated the purpose of skimming for scum. So after watching almost all of the new Jane Eyre film on DVD, I was finally in business.

Add another six hours, almost all of it unattended, and I was rewarded with eight quarts of a stock so flavorful, so rich, so “watch it wiggle and see it jiggle,” that even Cindi, the sitting Queen of Duck, deemed it the best she’d ever tasted.

It seems a coup d’état is brewing.

David’s Wriggle-riffic Duck Stock

Fear not, dear reader, the length of this recipe. It’s just me blowing a gale of hot air. All you have to do is roast, simmer, skim, reduce, chill. I just wanted to make sure every i was dotted and every t crossed. I don’t need you shaking your fists to the heavens because I was anything less than thorough.

Notes on Ingredients

- Duck necks–These meaty parts of the duck add incredible flavor to the duck broth. If you have a couple of duck carcasses left from a meal of roast duck or duck feet, you can add those in with the necks.

- Onion and carrot–Vegetables are added to the stock partway through the cooking process to enhance the flavor.

How to Make This Recipe

- Rinse the duck necks and dry them well. Toss the turkey necks with some oil and roast on rimmed baking sheets at 400°F until very dark brown.

- Add the roasted duck necks to a very large pot and pour in enough water to cover. Bring to a simmer and skim off any scum. Cook at a simmer for 1 to 2 hours, removing scum as needed.

- Add the onions, carrots, thyme, garlic, and tomato paste, and continue to cook until the meat is very tender. Add more water if needed to keep the bones and vegetables submerged.

- Strain the stock through a colander, then strain again through a paper towel-lined sieve. Repeat if desired.

Common Questions

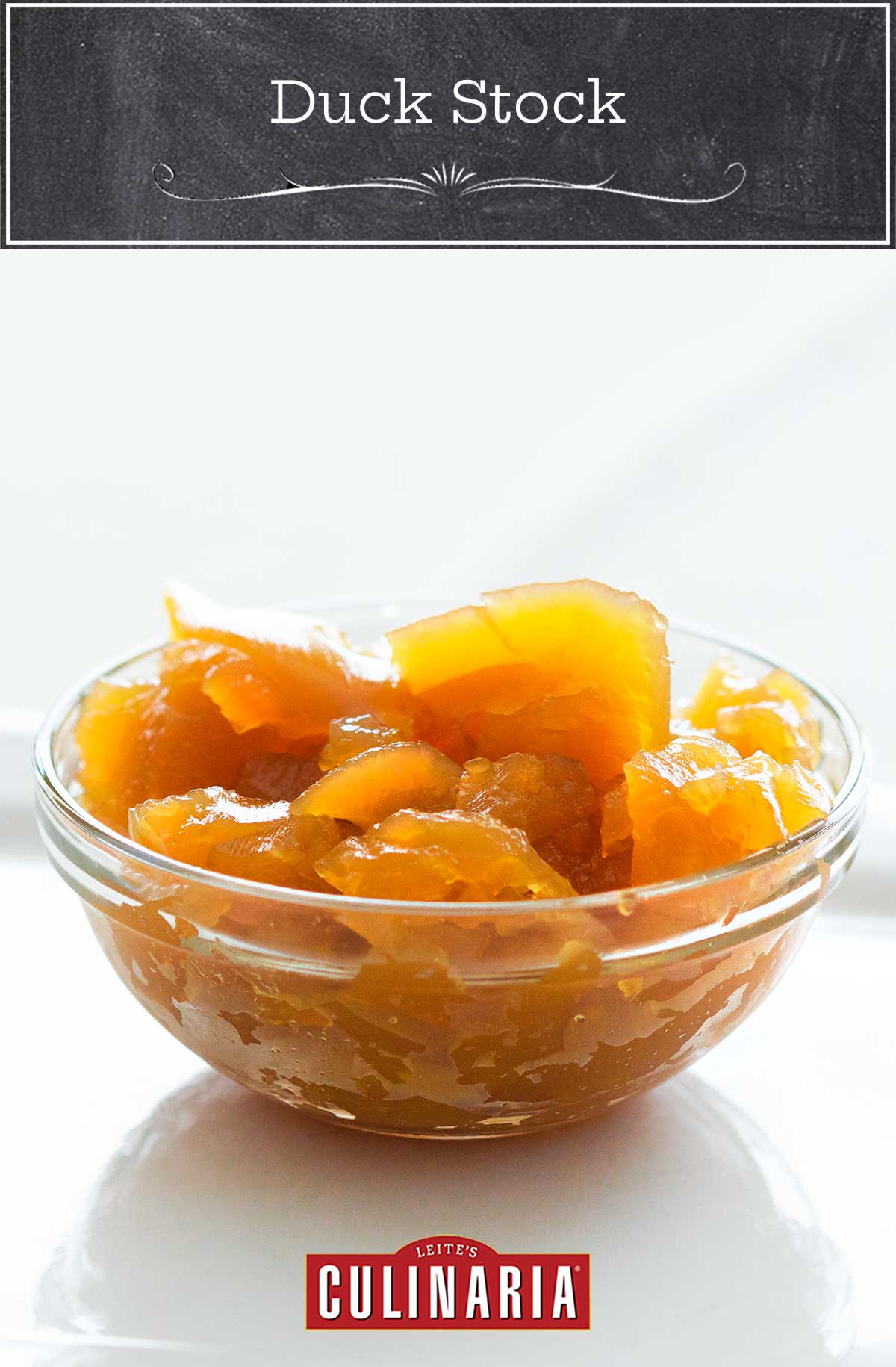

The image you see may seem to resemble a bowl of duck Jell-O more than duck stock. But actually, they’re one and the same. Sort of.

Behold the glory of an über-stock whose every molecule is imbued with collagen, that gelatinous substance that makes gelatin—or Jell-O, if you will—wiggle, jiggle, quiver, and shimmy. (This wiggling, jiggling, quivering, and shimmying is much like what happens to your thighs when you, like David, bust into an impromptu happy dance over the superlatively rich, ducky smack of this stock.)

Worry not: The wobbly blob of stock turns liquidy when subjected to mild heat. All the better for you to make a ducky take on pho or toss in some carrots and turnips and potatoes and deem it a duck pot au feu. The sort-of-solid stock freezes well, too, which gives you ample time to ponder what to do with the rest of your stash of duck stock. Er, über-duck stock.

While homemade duck stock makes an outstanding cassoulet, it can also be used in place of chicken stock for making jambalaya or duck risotto. Feel free to use it anywhere a rich stock-based sauce is needed. It’s also excellent for cooking rice or polenta.

Certainly. Freeze in 1 or 2-cup portions in resealable bags or containers for up to 3 months. If you find yourself needing smaller amounts of stock, freeze in ice-cube trays and pop them into a resealable bag when frozen.

Pro Tips

- If your duck necks come frozen together, thaw them quickly by running them under cold water until they separate.

- Making this homemade duck stock recipe is a slow process that cannot be rushed. Plan to make it when you are at home all day.

- This stock will keep for up to 1 week in the refrigerator. Freeze the stock for longer storage.

Homemade Duck Stock

Ingredients

- 25 pounds duck necks, fresh or frozen (ordered from D'Artagnan)

- Mild vegetable or olive oil

- 2 1/2 pounds yellow onions, roughly chopped

- 2 1/2 pounds carrots, peeled and roughly chopped

- Handful fresh thyme

- 4 garlic cloves, smashed

- 1/4 cup store-bought or homemade tomato paste

Instructions

- Slide an oven rack into an upper third position and another into the lower third slot in the oven. Crank the heat to 400°F (204°C).

- Rinse the duck necks in cold water and pat them very, very dry. Don't skimp on the patting-them-dry part, or the necks will steam instead of roast, which means you can say goodbye to those delectable caramelized bits of duck skin and fat that ought to stick to the baking sheet and impart an unspeakable amount of flavor to the stock.

- Line two rimmed baking sheets or roasting pans with aluminum foil. Dump a few big handfuls of duck necks onto the pans, drizzle them with some of the oil, and toss to coat them well. Place the necks, side by side, in a single layer. Any extra necks will have to wait for the next batch.

- Roast the necks, turning them several times, until they turn a deep mahogany and the bottoms of the baking sheets are glazed with anatine goodness, 45 to 60 minutes.

- Meanwhile, find a very, very, very large pot. Barring that, two large ones. Using tongs, transfer the necks to the pot(s) as they come out of the oven and forget about them while you roast the rest. I ended up with nine baking sheets' worth of necks; they took quite some tIme to roast, although it was mostly unattended.

- If you like, when you're done roasting, slide the empty baking sheets on top of the stove and turn the burners beneath them to medium. Drizzle in a little water, scrape up the browned bits with a spoon, and pour the liquid gold into the pot. Every bit counts.

- Add enough cold water (not warm or hot but cold) to cover the necks by several inches. Bring the water to a gentle simmer—the kind that sends up fairly steady columns of lazy bubbles—and let time work its magic. Skim any scum that forms on the surface. Depending on the size of your pot, this will take anywhere from 1 to 2 hours.

- Once the scum has pretty much been removed, add the onions, carrots, thyme, garlic, and tomato paste to the pot (or divide them between the two pots). Let the stock burble until the meat easily pulls away from the bones, 4 to 6 hours more. Keep an eye on the pot so the bones and vegetables remain submerged. If the stock level drops too much, pour hot water into the pot.

- Place a colander in a bowl or pot large enough to hold a vast quantity of stock and carefully pour the stock into the colander to catch the large bits and bobs of meat and bone. (Watch out, it’s hot!) Toss out the contents of the colander, because if the stock was cooked properly, the liquid will have leached every last iota of flavor from the meat (although the remnants did make a great meal for our Devil Cat, Rory). Wash the pot well and set it aside.

- Line a fine sieve with several layers of paper towels and place it over the pot. Slowly pour the stock through the sieve. Let the stock filter through, without pressing on the paper towels. If you’re a perfectionist or simply like a perfectly clear, shimmering stock, you can repeat this step once or twice. The stock will still be hot, so set aside the pot until it’s cool to the touch.

- Pour the stock into resealable plastic bags and place them in the fridge until you need them. The stock will last up to a week in the fridge or 3 months in the freezer. You can also pour the stock into ice-cube trays and slide them into the freezer; when they’ve frozen, pop them out into resealable plastic bags—though I don’t recommend doing that with all 8 quarts of stock.

Notes

- Thawing–If your duck necks come frozen together, thaw them quickly by running them under cold water until they separate.

- Don’t rush the process–Making this homemade duck stock recipe is a slow process that cannot be rushed. Plan to make it when you are at home all day.

- Storage–This stock will keep for up to 1 week in the refrigerator or can be frozen for up to 3 months.

An LC Original

View More Original RecipesNutrition

Nutrition information is automatically calculated, so should only be used as an approximation.

I have a stock question. For years, I have made chicken stock, and for years, i have been disappointed. I have followed one recipe after another, and they all said the same thing — chicken (bones or whole or parts) plus aromatics, plus simmer for 2 or 3 hours. And every single time I wound up with an insipid, nearly tasteless liquid, maybe one step up from a very virtuous sort of herbal tea.

I followed the same sort of recpe for Batch #1 (see above) and then decided NO. NO MAS. This is an insult to the pot. So I put the usual stuff in, but then I added maybe 2/3 of the recommended amount of water. And THEN I simmered the stuff not for two hours or three, but for a solid twelve.

The result: Fabulously delicious, golden liquid, doesn’t even need a speck of salt. So here’s my question: WHAT IS WITH ALL THE SIMMER FOR TWO HOURS RECIPES? I have tried enough of them to be quite certain that it’s not that I am somehow getting weak, insipid chickens. That’s simply not enough time to develop any flavor or body. So…..what is the story? Any ideas?

Maggie, the simmering is a way of extracting all the flavor from the meat, bones, and vegetables as well as reducing the stock. My guess is you might not have simmered it down enough to concentrate the flavor. I usually reduce my stock by half.

I am currently simmering Batch #4 of chicken stock (total count: About 12 quarts — welcome to having 24 people for Seder!), and I have become a stock junkie: There is something so incredibly pleasant about allowing time (my favorite kitchen ingredient) to transform stuff that is all but trash — bones, gnarly bits, feets (my secret ingredient) — into that lovely golden stuff. And you’re now inspiring me in the Ducky Department. A month ago, 25 pounds would have sounded daunting. Now? HA! I LAUGH at your 25 pounds!

I bow down to you, Maggie! I am not worthy, I am not worthy!!

Hi, please can you clarify a point for me? If the duck necks were initially frozen and then cooked, can you refreeze the stock? I was always led to believe once something is defrosted it shouldn’t be frozen again?

Hi Ellyn, absolutely no problem with freezing the stock. That no-freeze rule, as far as I was told, refers to defrosting an item–say meat–and refreezing it uncooked. This takes frozen necks that are used in the stock and then that stock is frozen. It’s the same way we often buy pork sausage when it on sale and freeze it. Then we make a chili with it, eat some, and freeze the rest.